Hey Team,

Geeta, the image you offer of your teenage self decked out in Manchester black makes me feel misty. It invokes memories of my frosh year in college, when my roommate Laurel pushed my Kate Bush records of the stereo to make room for Bauhaus and the Cure. And then I picture my own tween daughter, a self-christened “Goth” who likes to don black lipstick and her velvet-and-lace Halloween costume to go to the mall in the Alabama town where we live. (She really stands out in crowds exclusively clad in Crimson Tide apparel!) The vampiric circle of life connects the teenage kicks I got from Peter Murphy intoning “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” to her adoration of Edward from Twilight. The pop culture seascape, littered with images, sound, and themes that bob from the depths to the surface and back again with each passing era, is the ultimate realm of the undead.

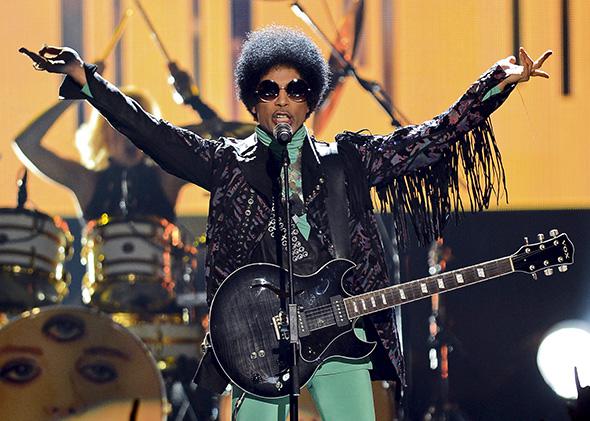

Just this morning I read a great essay by Brad Nelson about how two buzzed-about bands incorporate layers of past sounds into their fresh songs. The Californian sisters in Haim and the English high school buddies in The 1975 (even that name brings the past into the present) are all veteran musicians in their 20s; even more than the average post-adolescent music obsessive, what they heard and tried to emulate made them who they are. Nelson quotes The 1975 bandleader Matthew Healy, explaining how his consciousness developed in embryonic attachment to one vintage genius’s sound and vision: Sign O the Times. He became preoccupied with the 1987 concert DVD, so much so that it dominated his inner life. “The DVD of that, for probably about 20 percent of my life is the screensaver to my brain. If I wasn’t thinking about something, I was thinking about Sign O the Times by Prince.”

The phenomenon of young bands borrowing from certified geniuses is nothing new in pop. The same goes for mid-career artists like Thicke, who before selling his soul to Pharrell spent a decade tastefully emulating his heroes as a mid-level R&B loveman. Geeta, I’m gonna leave the neutron bomb you dropped on “Blurred Lines” alone except to say that its musical magpie-ism strikes me as no more egregious than One Direction’s delightful pillaging of power pop’s treasure chest throughout its new album Midnight Memories, or Vampire Weekend’s loving remake of “Step to My Girl” by Souls of Mischief on the B-side to the lead single from its poll-topping album Vampires of the City, or Ed Sheeran’s blatant rewrite of the Black Crowes’ “She Talks to Angels” in “The A Team,” a 2011 song that crawled into the Top 40 around the time 2013 began. Scratch the surface of a hit in 2013, and you’ll find five more underneath.

I’m unusually aware of that lately because I’m working on a book manuscript that spans the history of popular music, and this year I spent much of my time immersed in the archives. For that reason, I’ve seen many recent controversies and celebrations as connected to similar events in previous eras—especially the 1920s. Roaring ’20s dance crazes were mirrored in the viral spread of the Harlem Shake in late winter and in Miley’s appropriations of bounce and twerk, which reminded me of Ann Pennington dancing the Black Bottom in 1929. Justin Timberlake’s touring band the Tennessee Ten seems to have been named after a jazz ensemble from that era, too. This was all made explicit, of course, in Baz Lurhmann’s hip-hop remake of The Great Gatsby and on its soundtrack, whose highlights include Bryan Ferry’s big-band reworkings of Roxy Music chestnuts (also featured in his swellegant album The Jazz Age) and “Where the Wind Blows,” in which Coco O. from the wonderful Danish duo Quadron does her best Ethel Waters impression over a scratchy ragtime piano sample.

The Great Gatsby was only a middling success in a year of great movies about music. My favorite was about many other things, too: Steve McQueen’s stunning 12 Years a Slave brought us back to the horrific cornerstone of our national history, the slave trade; it also showed how music has been both a liberating force for the oppressed and a source of undeserved comfort for oppressors. More obviously about music, the Coen brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis is both a cautionary tale about how hard life is for workaday guitar strummers and an anthology itself, its performance scenes meticulously crafted to capture the nuances of the early Greenwich Village folk scene. On the smaller screen, Steven Soderbergh and his stars Michael Douglas and Matt Damon brilliantly interpreted the high-kitsch tragedy of Liberace in Behind the Candelabra. And as for documentaries, they just keep coming: Sound City; Twenty Feet From Stardom; Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer; The Punk Singer (I’m actually in that one); A Band Called Death; Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me; Muscle Shoals. I could go on.

We’re living in the golden age of learning about other musical golden ages. Music docs are flourishing in part because the technology needed to create them has become so much more accessible. The same goes for archives, which range from the most official—the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Library and Archive, which opened its glorious doors to the general public this year—to the most intimate fan collections, now often available online. (I’d include blogs like Chris O’Leary’s Bowie lexicon Pushing Ahead of the Dame as part of music’s archival renaissance, for example.) And then there’s YouTube, the uncontrollable archive, where new old stuff its posted every day. (Among my faves: the moldy-fig postings of collectors of 78 rpm recordings, who show themselves lovingly putting the needle down on their fragile treasures.)

This time-traveling free for all has significantly altered the business of reissues—the 20th century way we music nerds learned about what had come before us. Packaging matters more than ever when the music itself can so often be tracked with the click of a touchpad. One of the most significant musical events of 2013 was the release of the Paramount Records Wonder Cabinet, a veritable piece of furniture (that’s how Jack White, whose Third Man label issued the thing along with Revenant Records, describes it) chronicling the history of one of the last century’s most important music labels and containing—physically, but also virtually, through a magical download code—800 songs from a mind-boggling array of artists whose music invented country, blues, jazz, and gospel. The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records also includes the most extensive liner notes I’ve ever seen, and reproductions of myriad original label advertisements.

While my year’s been deeply enriched by other fabulous reissues, including the stunning gospel collection I Heard the Angels Singing: Electrifying Black Gospel From the Nashboro Label, 1951–1983, the recovered African gem Who Is William Onyeabor?, and complete sets representing Harry Nilsson and Sly & the Family Stone, I don’t actually own the Wonder Cabinet. It costs nearly $500, and my money was marked for Hanukkah presents and a new Ninja blender this year. (Gotta have my smoothies.) Such is the reality of reissues now: high-end sets do best, offering an aura-soaked object to those who long for such luxury goods. But I’m delighted it was produced, especially with White’s involvement, because such efforts bring the archival process out of the musty corners of the library and into the consciousness of general listeners who are participating it already, every time they click on an old Guns ’N Roses video—the nearly 20-year-old “November Rain” mini-movie is the site’s most watched rock clip, with similarly vintage vids by Oasis and, believe it or not, USA for Africa in the top five.

Because of the timeless, seemingly limitless existence we share in cyberspace, popular music’s fundamental values are again up for debate. This happens every time a new technology takes over: When people started singing into microphones; when the radio entered every home; when MTV and Michael Jackson invented the “visual album” Beyonce’s lately all about. What’s the root of anything, when the Internet’s Mariana Trench always offers something older and more obscure? Who can claim originality when it’s so easy to trace the borrowings that make up every song? What is an authentic musical experience for a kid like Matthew Healy, who moves through life with a Prince DVD lodged in his brain?

Carl, maybe you can take a stab at such eternal questions. Is the answer somewhere between the Avett Brothers’ country cabin and the glowstick-littered floor beneath Avicii’s DJ booth throne? All I know is, my kid really got into Boney M. this year, because the YouTube superstar PewDiePie did a silly dance to “Rasputin.” So that space-time collapse we’ve been talking about is all right by me.

Wake me up when it’s all over,

Ann