Dear fellow ruminators,

This exchange has been ridiculously stimulating and challenging. Thanks for the suggestions (downloading those Cassie mixtapes right now, Lindsay) and the shout-outs to music I wrongly overlooked on my lists—Will, Theo Bleckmann’s version of “Army Dreamers” is my fave Kate Bush cover evah. We did a darn good job covering pop’s bases in the midst of Yule logging and/or getting Chinese and a movie on this chopped and Scrooged holiday.

However. There is one subject we’ve mostly left untouched, maybe because it’s such an uncomfortable one. Jason opened the door for us to discuss Rihanna’s strange year of triumphs and provocations, pointing to her influence on the nature of stardom itself, which grows in direct proportion to her obnoxiousness. I was really hoping one of you would enter this treacherous area, but I’m up last, so here I go.

I call Rihanna obnoxious even though I’m her conflicted (and lately fading) fan, because I think it’s important to acknowledge that this massively successful 24-year-old is an active player in a narrative that drives culture-arbiters like us crazy. How could she? we ask ourselves on repeat as she consorts with her prototypical Wrong Man, indulges in excess that’s highly inappropriate for this age of austerity, and cranks out hit after mind-numbing hit. (I’m particularly peeved by the one that I associated with a sweet ad for Comfort Inn until she seized and strangled it.)

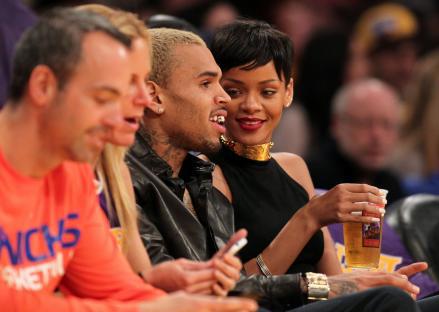

Just like the rise of the Real Housewives and Honey Boo-Boo, Rihanna’s saga implicates all of us, because we’re the ones following her on Twitter, downloading her duets with that thug (her word, not mine), and returning to the 2009 police report of her beating at his hands, all while sternly saying our interest is strictly cautionary. In response, Rihanna play-acts rebellion in ways that wreck observers’ expectations. She’s a victim? It’s nobody’s business. (Billie Holiday sang that once, too.) She’s a survivor? She declares herself ready to die. She’s finally free? “Boy, I just wanna be in your possession,” she sings, cuddling Chris Brown courtside.

Those last examples all come from this year’s Unapologetic, an album that vexed even the critics who liked it. Its mix of what seems disturbingly personal and what works as purely commercial supports Rihanna’s projects of taking hold of her own story and refusing to make it palatable. As I’m reading her motives right now, they align with those of many famous women who’ve come to experience public life as a violation. Choosing a companion others condemn is a time-honored way of poking holes in a confining persona. The most relevant comparison to Rihanna is Whitney Houston, whose love for a dangerous bad boy contributed to her eventual destruction. But you can go all the way back to Fanny Brice, who married the low-level gangster Nicky Arnstein in 1918, a choice that put a dent in her flourishing vaudeville career.

Brice’s disastrous marriage also gave her a signature song: “My Man,” which is so close in spirit to some of Rihanna’s recent ballads that I’m hoping for a David Guetta remix. Pop audiences have always fed off the pathos of stars. Want inspiration? Listen to this speech by Lana Wachowski—or the latest Pink album, The Truth About Love, which deals with many of the same issues that fascinate Rihanna but has more humor and wisdom, not to mention serious belting.

If Rihanna’s music fails to inspire or instruct, it does continue to do something unexpected. Her voice comforts. I’m always surprised at how many writers use words like “blank” or “distanced” to describe Rihanna’s voice. I think its limitations—a constricted range, no falsetto, no real sense of phrasing—make it all the more believable, communicating uncertainty and an acute awareness of pain. No amount of Auto-Tune removes her blue tinge, and strangely, it becomes a salve. The first 10 times I heard “Diamonds,” her latest (Sia-penned) club banger, I hated its chirpy, overenunciated hook. By the 20th time, though, I started to notice the way Rihanna sings the chorus’s final word, “sky”: She descends into it with all her weight, like she’s tired but determined to protect herself and her beloved. That heaviness, communicated through unflashy moments of pure feeling, injects calm and tenderness into the swirl and clatter of Rihanna’s music.

I think this submerged, soothing quality factors into Rihanna’s stunning popularity. Who didn’t need a bit of succor in such a difficult year? The children’s choirs that popped up everywhere after the Sandy Hook tragedy struck me as maudlin; yet the mere tone of young voices harmonizing did calm the nerves and help the tears flow a little more gently. I want to leave you with this notion of comfort, an often overlooked but crucial offering of pop music. And the great imperfect voice that conveyed it better than anyone’s in 2012 belonged to Leonard Cohen.

At least one high-profile ersatz choir—the cast of The Voice—turned to Cohen’s much-abused modern hymn, “Hallelujah,” in the wake of Sandy Hook. There’s no need to go to that old saw. In February, the 78-year-old guru-rabbi-king of the ladies’ men released Old Ideas, a song collection that communicates everything necessary about loss: how much it hurts, how the mind tries to make up for it, how it owns every mortal in the end. And, crucially, Cohen dwells deeply within the reality that loss defines being alive. His baritone a snowy croak lit up from within, Cohen cries with the pain of a shattered heart. But as always, he welcomes the brokenness:

If your heart is torn

I don’t wonder why

If the night is long

Here’s my lullaby

Sweet dreams,

AKP