Well then, fellas,

Let’s talk about misogyny. Thanks, Jonah, for recognizing that the incredible innovation surging through the underground hip-hop and R&B scenes rarely extends to confronting gender prejudices. I love to hear young rhymers throwing sparks—my faves include the Philly-né-Atlanta poet Sugar Tongue Slim, the East Bay circus-barker Lil’ B, the Compton cosmopolitan Kendrick Lamar, and the Deep South strivers Big K.R.I.T. and G-Side. Someone turns me on to a new mixtape every day, it seems, and it’s so much fun. But I’m always waiting for the moment when the “bitch” bomb gets dropped or the stripper fantasy is played out.

Woman-hatred may be too active a term here. (Except when you’re talking about Tyler, the Creator, whose Odd Future posse splashed as 2011’s first huge Internet phenom—I view him as a classic Freudian gynophobe with castration anxiety.) Most rappers display an attitude that’s more careless than cruel. The objectification of women is embedded in hip-hop’s very terminology; at some point, the earthiness of the blues and the swagger of original rap turned virulent in service of pimp fantasies, and sex became more like an extreme sport than a love game. I remember seeing Diddy (then Puffy) and Lil’ Kim go at each other at a late-’90s Madison Square Garden show, and thinking, “That’s not love, it’s not even lust—it’s war.” At least Drake and Nicki Minaj seem to actually like each other.

It’s interesting, though, that hip-hop’s most audible voices are not just coasting on male supremacy, but confronting its limits. I agree with you, Jonah, that Kanye seems to have given in to his baser instincts: My least favorite verse of the year is that one from Watch the Throne’s “Niggas in Paris” in which ’Ye demands that his gold-digger girlfriend ball him in the bathroom stall. Elsewhere on the album, Jay does shower Beyonce with compliments, reveling in power-coupledom. But that track is still called “That’s My Bitch.”

Black male rappers have always expressed solidarity with the women they objectify. Racism marginalizes them the same way sexism and racism limit the queen-whores they idealize and use. The sympathetic stance reached a bizarre apotheosis in Lil’ Wayne’s sensitive smash, “How To Love,” a well-meaning bit of condescension toward a sexually empowered woman that, in its video, equated anything but married life with an HIV death sentence. I know Weezy meant well, but in a year when women’s reproductive freedom was challenged in terrifying ways, he was part of the problem.

Some critics think Drake is part of the problem, too. In a dialogue we posted at NPR Music, my fellow critic Frannie Kelley expressed repulsion at his narcissism, his laziness, his being the kindof date (she’s certain) who would go through a girl’s phone while she’s in the bathroom. I agree with Frannie that Drake’s not even trying to pretend he’s anyone’s ideal man. (He’s got that Omega Male swagger.) And he throws around the “B” word so much, it becomes like a mantra.

Yet Take Care was one of my top albums this year (you can find my top tens at NPR Music) precisely because its fifth-drink-of-the-night aura feels so relevant to a socio-cultural moment that damn well better pass soon. Yes, Jody, this is a recession album: the groggy drift of a boom becoming a bust. The creative team helmed by producer Noah “40” Shebib builds grand, chilly frameworks for Drake’s musings; they feel like mansions emptied for foreclosure. The interlocutor himself, really a monologist, lets his dumb lines stand and his inner conflicts brew. Like I’ve said before, he’s not emo, he’s grunge—he feels stupid and contagious, and he doesn’t quite know how to entertain us, or if he should.

The fantasies Take Care explores are always precarious, guaranteed to dry up the minute Drake’s credit card goes into overdraft. He mumbles on about his wealth and fame, but he nearly always connects them not to freedom but to obligation: Money is a burden he’s terrified will fall off his back. His friends expect him to pick up the tab. His women want to be “sponsored.” His family, whom he does seem to trust, enjoys his spoils but not his company. The answering machine message from his grandmother at the end of “Look What You’ve Done” features her thanking him for support and saying, “I hope I’ll see you,” in the sad tone older people use when they know they’ll be eating alone that night in the retirement home. The listener imagines Drake hearing the message somewhere far away, keeping the recording to remind himself that somebody believes he actually cares.

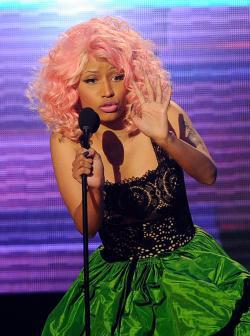

And so Dreezy Downer and his languorous jams make beauty of (both kinds of) depression—except when he pairs up with a woman who kicks his sullenness to the curb. Rihanna can do it, but Drake’s main loving adversary is, of course, Nicki Minaj, whose hit “Super Bass” inspired my daughter’s Halloween costume and introduced a delightful new ideal for rappers: Get in touch with your feminine side. I’m totally into Nicki. Frankly I’m glad she “sold out” and went Barbie, because as I see and hear it this living doll pulls her own strings and parodies the beauty myth with every bat of her fake eyelashes. She’s Debbie Harry to Kesha’s Adderall-addled Chrissie Hynde: the mainstream faces of a bubbling-up of women in hip-hop that reminds me so much of the moment punk turned into New Wave, it makes me wanna dance and laugh and cry and get all pelican fly.

These door-knocker upstarts aren’t much for political correctness—Kreayshawn and her White Girl Mob stepped in a steaming pile of racial politics while grabbing the Internet’s attention back in June, and Azealia Banks, my personal fave, makes meat of her (bisexual) conquests as gleefully as Ludacris has ever done. Thee Satisfaction’s Stasia and Kat, hailing from the riot grrrl Pacific Northwest, aren’t too keen on labels like “feminist.” But the energy of these women could change hip-hop—if old school gatekeepers are willing to recognize them as equal players. To that end, can we please start calling Kesha a rapper? Listen to this NSFW track if you need more proof.

I’m almost ready to move beyond hip-hop and get to Adele—I don’t find her boring!—but first, let’s dwell on an album less concerned with getting down than with expanding consciousness. Black Up by Shabazz Palaces, the long-awaited long-player by the loose collective that includes Thee Satisfaction and which is led by former Digable Planet and current Sun Ra/Sly Stone/Miles Davis legacy bearer Ishmael Butler, fractures hip-hop’s set narratives into mirror mosaics of psychedelic sound. Grounded in African rhythms and free jazz cadences, imbuing gritty street scenes with a surrealist aura that Amiri Baraka would admire, Shabazz Palaces does what hip hop needs, now and always: It renews its lingua franca. Black Up made me hear everything new this year.

The clock’s telling me it’s time to pick my little Nicki fan up from after-care, so Adele will have to wait until my next missive, unless Carl wants to take her on. I do believe success is all wrapped up in the stuff our favorite Celine Dion philosophe addressed in his wonderful book on pop and taste. It’s not misogynist to hate Adele, exactly, but she is a woman’s woman. Sometimes the sound of a woman’s voice can be incredibly healing. Just ask Gabrielle Giffords, the year’s most remarkable comeback kid, led back to language by one of Nicki Minaj’s role models, Cyndi Lauper. I’ll leave you for now with this amazing example of female power. It’s at 3:17 in the linked video: Giffords singing “Girls Just Want To Have Fun.”

Let’s have this moment 4 life,

AKP