Jody, Jonah, Ann, and Carl,

A million thanks for letting me join you this year—I’ll try my best to keep up with some of my favorite writers. To start, though, I have to step back and agree with Ann about something, or one thing among many: that Kanye line from “Niggas in Paris”? The one where someone needs to prostrate herself (and run to the bathroom stall) to prove she’s worth West’s attention? The one that makes his sex life sound like it operates on the same basic principles as Fear Factor? Yes, that’s been bugging me for months now, too. (Something about hearing the song performed three times in a row at Madison Square Garden made matters worse.) Last time I complained about it, strangers accused me of being no fun, or a prude, but I think I might even have objections to it beyond the obvious moral ones. Like Jody mentioned, the really intriguing parts of Watch the Throne were the ones that found Jay-Z and Kanye ruminating on their own success and how it fits into bigger pictures, like the post-Civil Rights trajectory of black America or the culture of the wealthy. And on a record where these guys are occasionally thinking hard about wealth and power and what they mean, Kanye keeps lagging; with That Line, he comes up with the fairly boring answer that, hey, one thing you can do with money is exploit people.

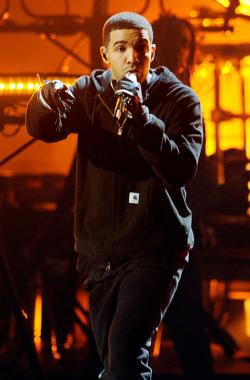

Maybe that’s a good excuse to talk about our young “Compton cosmopolitan” Kendrick Lamar, whose album Section.80 wound up among my personal favorites. I’m tempted to propose some analog of the Bechdel Test for albums by male rappers—does the MC A) have a conversation with a woman B) that’s not about himself C) or a business transaction?—just so I can say Lamar passes it. When he picks up a woman at a house party, the first thing he wants to talk to her about is how their generation was born in the crack era and why they’ve been damaged by it. He has a lot of ideas about that sort of thing. Then again, he also has that old, bad habit of using women as tragic symbols and cautionary tales, not unlike the Lil Wayne track Ann mentions: They’re broken, or wracked with insecurity, or victimized. Lamar seems wrong about a lot of stuff, and weird about a lot of stuff, and dedicated to plenty of orthodox hip-hop postures, but there’s something about the dogged, reaching seriousness with which he chases big ideas that always charms me. (As does his production.) I always associate him and Drake with the “deep” guys in college dorms who try to impress women by going on about how grave and weighty life is—but in that fantasy scenario, Drake would be sitting on a futon shaking his head about his ex-girlfriends while Lamar would be leaping around spinning elaborate theories out of things he learned in his political science lectures.

As you can probably tell, I was so-so on that Drake album, despite the lovely production. (It occurred to me yesterday that I feel about it the same way I do about Bon Iver’s LP: There’s a lot of wandering beauty, but a weird lack of frame or spine to hold it together for me. Like a pie without a crust.) Looking over my top-ten list, I’m worried Drake is one of few Canadians I didn’t like—this year’s favorites have a disturbing tilt toward indie acts with roots somewhere up there. This doesn’t reflect any sudden explosion of creativity north of the border or anything; I’ve just never been good at making lists that aren’t extremely subjective. So I’ve got Destroyer’s Kaputt, on which Dan Bejar makes a remarkably good stretch of new-wave soft-rock, then mutters cryptically over it like a baby-faced Leonard Cohen. And the Toronto act Austra, who make chilly synth-pop with an operatic shudder and a real sense of purpose. Then there’s Colin Stetson, a Michigander who moved to Montreal, and whose process takes a second to describe: He plays a bass saxophone, uses circular breathing to produce endless flurries of notes, and sticks microphones everywhere until the sound’s three-dimensional and the slap of his fingers on his instrument sounds like drums. Occasionally Laurie Anderson intones a text over that. It’s not nearly as esoteric as that description makes it seem; the album Stetson released this year, New History Warfare Vol. 2: Judges, is captivating enough that I played it as often as any more workaday pop I loved. (I also threw together 50 favorite tracks on a Spotify playlist, with a better international spread.)

As for Adele, I’m not quite bored by her, but I worry I’m boring about her. I always wind up figuring that she makes a very traditional, demographic-spanning variety of pop; and she makes it exceedingly well; and it is no wonder that so many people buy and love it; so, good for her. There’s surely something, though, to be said about her voice, which apparently invites the immediate empathy of “everyone with a heart and an iTunes account.” No, more than that: It creates the weird sense that Adele is singing because she empathizes with you, the person who bought her album. I suspect this is because Adele never really broadcasts any emotions, not openly. What she broadcasts is that she has emotions—big ones—but is being very adult and self-controlled about venting them. There’s a fury simmering on “Rolling in the Deep,” but she makes her threats with a clenched-teeth reserve. There’s some exhausted anguish behind “Someone Like You,” but the chorus even starts with the words “never mind”—she’ll graciously let things drop and get some closure. And given the amount of pop that’s basically a huge confetti-cannon of self-assertion and id and fierce demands, it makes sense that people would be primed to relate to someone whose emotions exist in the same world ours do, the one where feelings usually have to be choked back or controlled. We can’t all be as demanding as Kanye, even if we sell more records than he does.

I’ll save R&B for the next time around, except to say that it seemed interestingly scattered this year. (I keep wondering if the colorful club tracks dominating the Billboard charts have the R&B world shuffling around a bit, in search of new spaces to aim for—Beyoncé, for instance, made a very good album that felt like a newly married women telling her friends she hopes they have fun clubbing, but she has more serious stuff to attend to.) I don’t have many clues about where in the musical landscape to look for responses to our economic situation, either; Canadian indie records are probably not the answer on that front. But I will say that the one time the topic really lodged in my mind was while taking note of the great boom in buzzy, hyperactive electronic music that seems to be happening in the U.S.—not those club tracks on charts, but the over-the-top, face-melting variety that’s had hundreds of thousands of people turning out to rave-style festivals over the past few years. For instance: that former emo-screamer scene kid called Skrillex, who spent this year turning into a remarkably visible face. Whatever the quality of the music, it does seem to turn out huge, young crowds, whether in Florida or Idaho or Kentucky. And so far as I can tell, those crowds contain a good number of mid-American kids who just spent their teenage years hearing adults use terms like “foreclosure” and “layoff” while teetering precipitously around the lower middle class.

But on to Carl, who may have reason to question my outlook on Canada this year …

Nitsuh