Hello again,

This notion of “acteurism”—I first heard this term from my Village Voice colleague Melissa Anderson, but she cites Dave Kehr as its originator, as he’s programmed several series at MoMA under this rubric—has been very close to my heart throughout 2016. For starters, this was the year in which I took on several projects that required me to spend many months delving into the work of individual actors. Among other things, I devoted about three months to watching or rewatching every Jeff Bridges movie I could get my hands on and about six months to doing the same for every Denzel Washington film. (Denzel’s made about 45; the Dude, around 65. All in all I think I revisited about 80 to 85 percent of their filmographies. So, a lot of movies.) We’re fond of looking at directors’ overall careers—at the way their obsessions and style develop and meaning presents itself across multiple films. Turns out, when you look at an actor’s work in this way, you see something similar, even if performers themselves rarely write or direct their own movies.

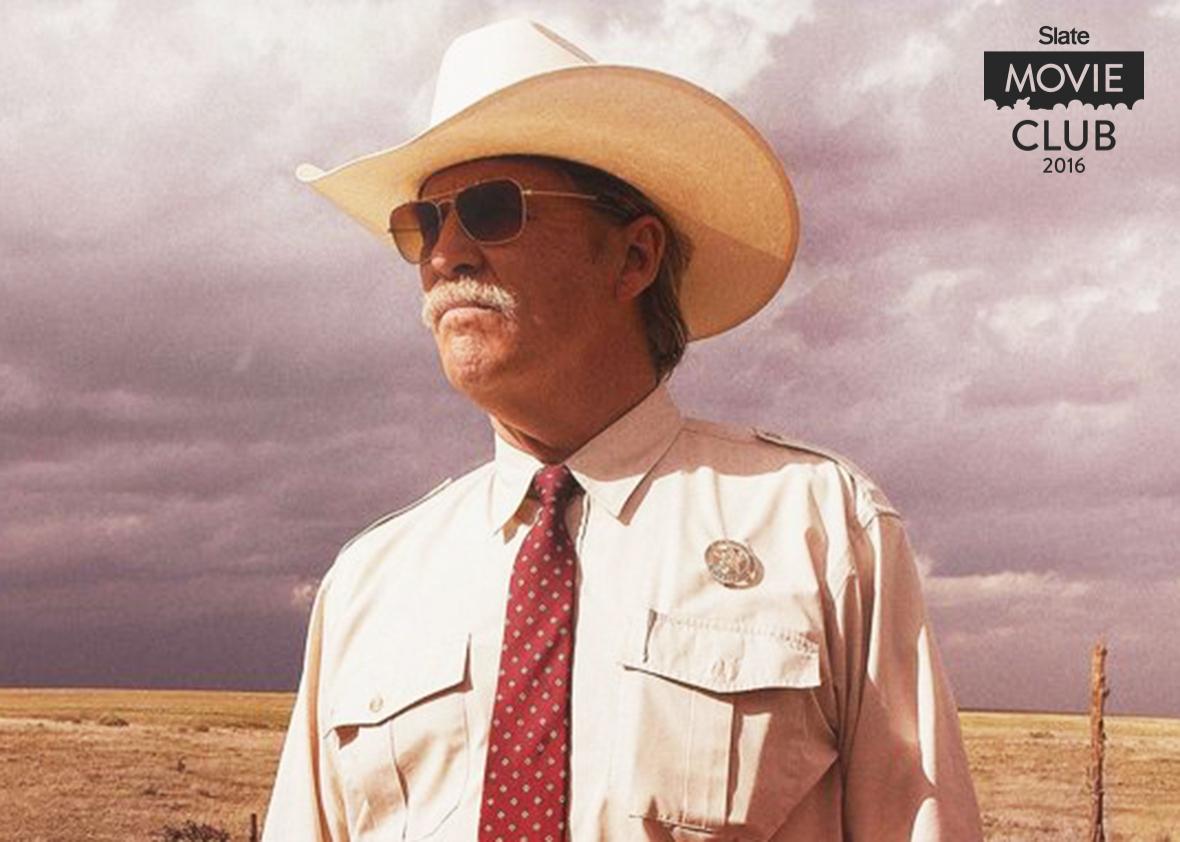

Jeff Bridges, for example, has always been a bit of a wanderer. In his early films, he’s the restless youth who knows there’s more out there somewhere. In recent years, he’s transformed into the weary cowboy type, but there’s still this self-awareness and easygoing rootlessness beneath what he does. (That’s just one reason why The Big Lebowski can’t work with anybody but him.) In this, he’s always been more reflective of his generation than actors such as De Niro or Pacino. So Mark, I think one reason why Hell or High Water works so well with Bridges in it is because he brings an openness to the part. To take two other guys who could have, on paper, played that character: He has none of Tommy Lee Jones’ stoic intensity nor Robert Duvall’s shamanic unpredictability. Those racist jokes of his would come off as mean-spirited and cruel out of Jones’ lips and as just plain batty out of Duvall’s. With Bridges, there’s always that slight edge of self-awareness—you can sense that he doesn’t really mean it, that he knows he’s just biding his time in a world that’s passed him by.

As for Denzel Washington—I’m not sure any other actor has given more transformative performances than he has. There are at least a half-dozen movies that would be pretty much terrible were it not for his electrifying presence. (The Hurricane, John Q, and Cry Freedom come to mind.) And even in recent years, as he’s done his share of somewhat disposable action films, he’s brought an uncommon level of vulnerability and cumulative anger to the roles. Look at the way his rage builds and builds in The Equalizer, or the way he wrestles with his own inadequacies and his failing body in Man on Fire. Performances like that make each new entry in the Denzel Kills Everybody genre worth looking forward to. (That said, The Magnificent Seven was kind of dreadful.)

Then there are films that seem like the part an actor or actress has been building to his or her entire life. Take Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Aquarius, in which the great Sônia Braga plays a retired music journalist battling a craven developer who wants to buy her out of her apartment and tear down her building. Their back-and-forth escalates from pleasant conversations to pissy confrontations to a war of attrition, and finally to a climax so howlingly melodramatic that I couldn’t help but cackle. The film’s narrative is reflected in its visual and sonic textures: Aquarius also manages to be about the legacy of Brazilian music, about preserving the past, about how the hiss and pop you hear on a record becomes a part of its story. But more than anything, it’s about Sônia Braga, about her face and her sensuality and the history of everything she’s done and been.

This year, we even saw a rather striking example of a performer taking over a documentary with Kate Plays Christine, in which director Robert Greene (whose previous film Actress is one of my all-time favorite documentaries) follows Kate Lyn Sheil as she prepares to play the part of Christine Chubbuck, the Florida newscaster who killed herself on the air in 1974. But the movie she’s preparing for isn’t real, and as things proceed, we sense a subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) struggle between Greene and Sheil over subject, style, and whether we should even be watching this in the first place. That struggle is by design— Greene appears to have structured his shoot to allow for it—but it’s also very real. It’s the damnedest thing: a movie that just keeps twisting and turning in your mind long after you’re done watching it. (And as if that wasn’t confusing enough, there was also Christine, a totally different and more traditional retelling of Chubbuck’s story, directed by Antonio Campos and featuring Rebecca Hall in one of her best performances. I saw the two movies at Sundance—almost a year ago—and my head still hurts from the double feature.)

As for Elle—Dana, I agree that Huppert’s incredible performance holds together a movie that’s a mess of contradictions. (She was on my ballot at the New York Film Critics Circle voting.) I run hot and cold on Verhoeven—I quite like a number of his films, but I’m that guy who didn’t like Starship Troopers or Showgirls when they came out, and still doesn’t. Funny thing about Elle: At Cannes, everybody said the film would be controversial and divisive, and yet there was very little evidence of that—most critics seemed to love it. It may be that this character is too specific, too weird for anyone to draw any universality from her actions. That’s a talisman of sorts, but it also threatens to undo the film—because I’m still not entirely sure she comes into focus by the end. Maybe that’s the point, but for me, Verhoeven’s blunt direction stifles the mystery. Still, he did have the good sense to cast and direct Huppert, so maybe he is a genius after all.

If studying the trajectory of an actor’s career opens up new avenues for appreciating or understanding a film, that doesn’t mean that we should abandon the idea of continuing to study directors as well. Martin Scorsese’s Silence culminated a 28-year odyssey by the filmmaker to bring Shusaku Endo’s novel about Portuguese missionaries in 17th-century Japan to the screen. A lot of people probably expected something stylized and grandiose, in keeping with some of Scorsese’s later movies, but the restraint, the refusal to overdramatize, feels like a return to the elemental. Even the fact that what little music there was in the film was this weird, distant droning … I mean, this is Scorsese we’re talking about, so it all felt like a response to the aggressive energy of his previous work. (Besides, if you want to see a stylized, brutal, in-your-face movie about Andrew Garfield suffering for the Lord in Japan, you can always see Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge, which is also quite good.)

For me, Silence does not exist outside of the context of its director’s career. That’s not to say that the film doesn’t work on its own—it absolutely does—but it’s hard for me to experience it in a vacuum. In particular, it resonates with two of my favorite Scorsese pictures, The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun. In those movies, we watch seemingly ordinary people come to terms with their divine destiny, while here we watch a holy man come to terms with his ordinariness. Endo’s book is the only novel I’ve ever read that made me want to believe in God. I don’t know if I can say the exact same for Scorsese’s film, but having seen it four times now (take that, comedies!), I can say it’s one of the director’s greatest achievements. And, with its immersive wide shots and unhurried narrative, it absolutely, positively must be seen on a big screen. If you watch Silence on a laptop or an iPad, you are committing a crime against cinema, and possibly against God as well.

Love,

Bilge