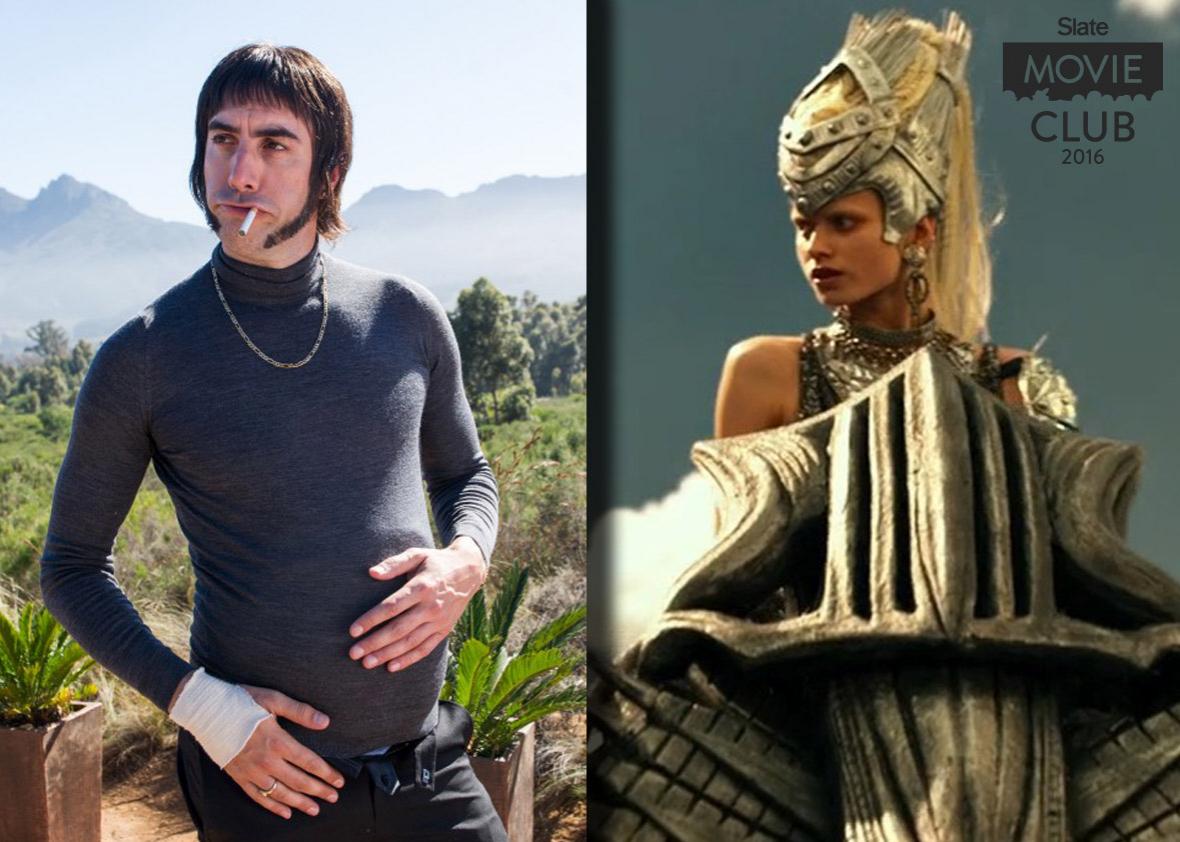

Bless you, Bilge, for that Brothers Grimsby plug. Sacha Baron Cohen’s grosser-than-gross comedy is a popcorn bucket filled with pubes. It boasts more testicles than the prairie oyster stand at the Iowa State Fair. And I laughed myself sick. (Or was I already sick for laughing?) I believe the only fair way to judge a film is by measuring it against its ambitions. Brothers Grimsby wanted to shoot whack-job slapstick inside an elephant’s vagina. It did, with gusto. Even so, when I filed my thumbs-up review, five weeks into a new job I adore, I sucked in my breath before clicking send. Sticking up for trash isn’t a fireable offense, but it does guarantee that for the next two years, any time I write a less-than-rave review of the latest DC gloommerung, some egg on Twitter will rebut, “Yeah, but your clearly a moron for liking Brothers Grimsby.” (Misspelling intended.)

So let’s hoist a pint to Grimsby and the other terrific trash of 2016. Gods of Egypt was giddy, gory, and glorious. I sat down primed to be irritated at the whitewashing of yet another ancient epic. (See also: Christian Bale as Moses.) According to Twitter, we were all supposed to be furious. But 10 minutes into the film, after watching 12-foot-tall babealicious gods hook up in a gilded Jacuzzi, I realized wishing Gods of Egypt were historically accurate is like wishing a doughnut were made of kale. It’s true fantasy, or as I called it at the time, “mythological mayhem.” For Christ sakes, the gods bleed gold. Director Alex Proyas (who was born in Alexandria, Egypt) even lets Gerard Butler keep his Scottish brogue. Plus, it made me fall head over heels for French-Cambodian actress Élodie Yung, whose vampy love goddess Hathor is Mae West in the body of a Victoria’s Secret Angel.

Gods of Egypt is the kind of fun escapism we keep saying we want and then shunning like it brought a six-pack to an AA meeting. Example No. 2: The Nice Guys. Ryan Gosling’s 30-second pants-cigarette-gun-newspaper–bathroom door shuffle is better choreographed than anything in La La Land. Like Bilge, I’m stoked to see The Nice Guys build a MacGruber-ian cult following. KFBR392 4EVA.

I also loved the orc half of Warcraft—kudos to Duncan Jones for fighting to give them more humanity than the humans—and every scene in The Shallows where Blake Lively talked to a seagull. While I’m at it, lemme throw in Fede Álvarez’s chokingly claustrophobic horror flick Don’t Breathe, which was so tense that my shoulders were in knots, and the much-better-than-you-expect teen thriller Nerve, in which another new fave ingénue Emily Meade crawls, sobbing, between two tall buildings on a slender ladder for social media likes.

I look forward to rewatching all of these movies on an airplane. Even The Purge: Election Year, though I wonder if it’ll still play as satire. And come to think of it, in 2017 I wonder how I’ll feel about Brothers Grimsby’s climax, in which a stadium of soccer hooligans triumphantly cheers, “Scum! Scum! Scum!” presaging every middle-finger brandishing @DeplorableRedneck Twitter handle by six months.

This comedies vs. dramas debate we’re having hinges on a key question: Is a classic defined by its rewatchability or its impact? Is the film canon shaped more by audience-pleasing favorites or by significant films I never need to watch again (Silence, Manchester by the Sea, and Toni Erdmann—sorry, but I only dug that last half-hour). The Academy Awards should be having this same debate, louder. I’d argue that the comedies that win, or put up a strong challenge, are barely comedies. They’re ticklers. You watch The Artist and Birdman, and every so often a sound comes out of your mouth—half-bark, half-grunt—that signifies pleasure. Yet, it’s not quite a laugh.

When’s the last time a real comedy won an Oscar? 1984’s Amadeus? It rankles that these liminal comedies are the only ones that win awards because they don’t have the guts to use laughter as a tool. They’re as soft and safe as toothless sheepdogs. But comedy can get away with saying anything. We forgive the gasps because of the immediate guffaw. It’s cliché to cite Blazing Saddles, but Mel Brooks’ bold, remorseless humor is the platinum standard of what comedy can do. It’s both impactful and rewatchable. Raise your hand if you’ve looked at a comments section lately and heard Gene Wilder deadpan, “These are people of the land. The common clay of the new West. You know, morons.”

There’s more social satire in one song from Popstar or any five-minute chunk of Sausage Party than in the entirety of The Artist. Wake me up when comedies like that are considered Oscar-worthy. No really, wake me up. I don’t mind spending the next decade asleep.

Before I fix myself a Hot Toddy, here’s one more thought about rewatchability. I tend to watch a lot of films twice: Once at their film festival premiere, and again when they hit theaters for an official review. Occasionally, a film will shift underneath me—that’s why I like watching tricky ones twice. Both Arrival and Jackie were better in November than September, but they hadn’t changed—I had. Or rather, the world had, and with it, my need for stories about people who communicate across a divide or take the White House seriously. Politics aside, the dead Daniel Radcliffe movie Swiss Army Man was, at first, a messy spray gun of fart jokes and wimpy why-can’t-I-get-the-girl chauvinism. It didn’t even make my Sundance top 10. But on the second watch, the movie cracked open, and I could see its beating heart. It wound up on my top 10 of the year.

A lot of the problem comes from sitting down with preconceived ideas about the film. I thought Swiss Army Man was going to be deep. Instead, it was a comedy. Then, when I expected a comedy, I realized it was deep after all. Because of cases like that, I try to avoid watching trailers at all, even though I feel like a monk in a cave when people start talking about the new Blade Runner teaser and I run back into the darkness pulling burlap over my head. Do you guys do the same?

Even if we’re conscientious, critics still run the risk of contagious hype. Take the premature coronation of The Birth of a Nation at this year’s Sundance. Nate Parker’s melodramatic period piece premiered 11 days after the Academy Awards nominated an all-white phalanx of actors—for the second time in a row. No wonder Birth of a Nation got a standing ovation before the movie even started. I thought it was dreck, and I suspect a lot of other critics thought so, too. Yet, when Fox Searchlight snatched it up for a record-setting $17.5 million, it was dutifully deemed the Film to Beat. Only after journalists relitigated the Nate Parker rape trial did people finally begin to whisper that it wasn’t that good. Twelve months later, just one out of 124 critics in the Village Voice poll even listed it on their 2016 top 10.

Maybe I shouldn’t be so honest about this. After all, what critic likes to admit her opinions can be—gasp!—wrong. But I like seeing my mind change. It reminds me that film isn’t just a fixed reel of footage. It’s an ongoing conversation. Maybe the deepest value of a film is by how much that conversation changes every time you share your life with it? We’ll see if Brothers Grimsby makes it to a third date.

xo,

A

P.S. For my money, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk had to be seen in high frame rate. Ang Lee cannily designed that twitchy, hyperaware unease to make us, too, feel like we had PTSD.