Dear Dana, Amy, and David:

Lucky me; I’m the guy in the restaurant who gets to hear what everybody else has ordered before choosing. Dana, I’m grateful for your marching orders; Amy, for your passionate challenge to my masculinity (about which more shortly!); and David, for your generous participation under adverse circumstances, which is a necessary reminder that a) it’s only movies—there’s no need to draw blood, and b) a year at the movies, even for movie lovers, is more than stentorian declarations about the very best or worst of what you saw. Sometimes it’s about finding yourself in front of The Intern at a tough moment, and not being completely ungrateful for the kind of tranquilizing refuge to which you can devote one eye or ear (or, in your dog’s case, to which you can fall asleep on the floor).

You three are critics. I’m more of an opinianalystorian-slash-whatever—and that’s a luxury; it means that I don’t have to wrestle myself to the mat when I feel ambivalent about a film, and also that I get to skip a lot of bad movies. (My top 12 films of the year in one handy place: The Big Short, Carol, Creed, The Duke of Burgundy, Inside Out, James White, The Look of Silence, Mad Max: Fury Road, Mommy, 99 Homes, Room, Spotlight.) With that in mind, Dana, I’ll take up your charge to offer a diagnosis of the movie industry in 2015. This feels a bit like the moment the president stands before Congress every January and says “The state of our union is STRONG!” and everybody rises and cheers even though half the people rising and cheering are muttering, “Yeah, bullshit,” under their breath. Nevertheless, here’s what I think: Things are mostly OK right now. I quite enjoyed Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and I was very moved by the indie James White. They are both movies, but one is a global business enterprise that has grossed approximately 6,000 times what the other has, so we can’t talk about blockbusters and indies as part of the same industry, only as part of the same art form.

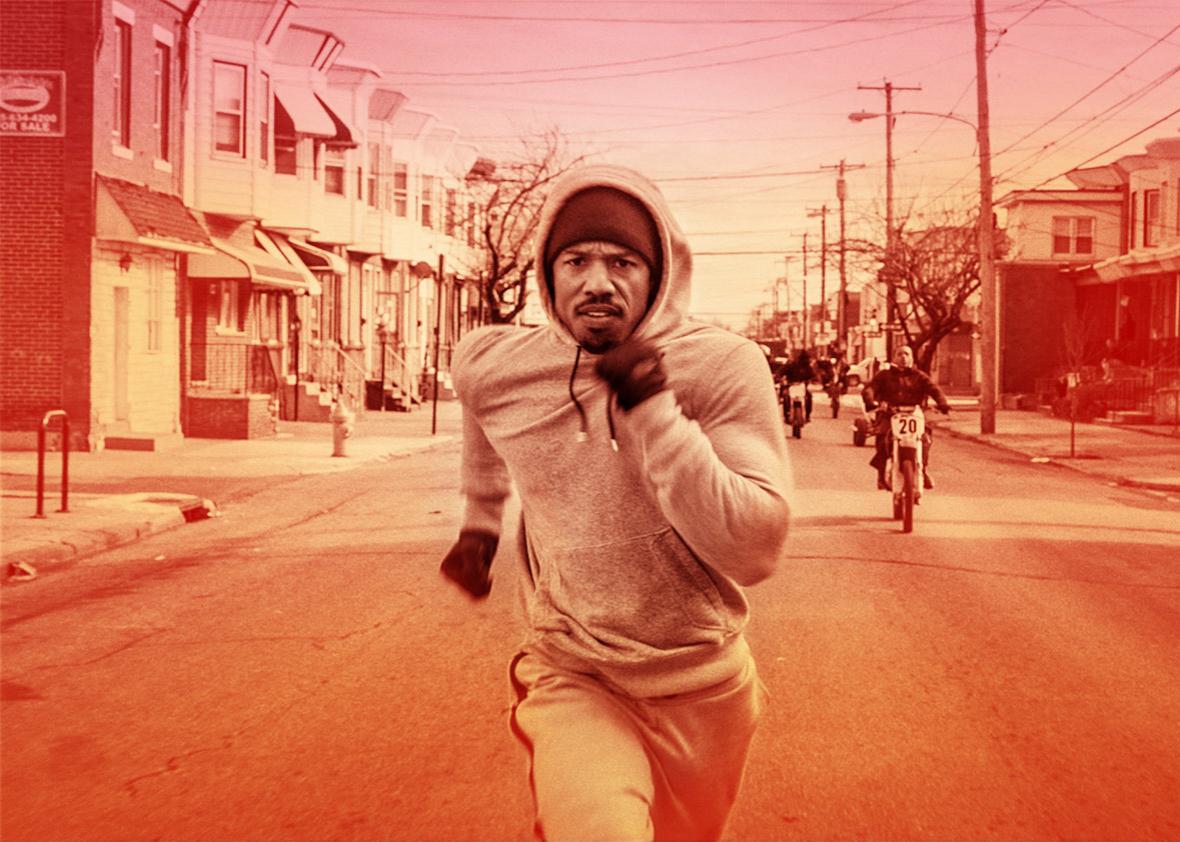

So let’s split ’em up. First, studios. One thing I believe is that there’s no such thing as a system that produces great movies, only a system that allows great movies to happen once every so often. Great movies—great studio movies or great Sundance movies—are always an exception. (Great anythings are always an exception.) Another thing I believe: There’s no point in rooting for failure; it won’t get you what you want. The fantasized collapse of the blockbuster ecosystem will not lead to studio executives saying, “OK, I guess we have to make midbudget script-driven passion projects now”; the most one can hope is that the success of these giant franchise movies bankrolls not only other giant franchise movies but some interesting gambles chosen by people with taste and enterprise. Universal is a pretty good example—the studio had a boom year due to Jurassic World, Furious 7, and Minions, and if that kind of cushion makes it easier to greenlight movies like Trainwreck and Straight Outta Compton, that’s an acceptable trade-off. Also, I have nothing against big movies—my list of favorites this year includes reboots of franchises (Mad Max, Rocky), one-off smash hits like Inside Out, smart and expertly executed studio movies like The Big Short, indies, and micro-indies.

In terms of business, the category that suffered ominously this year was midrange independent filmmaking. Small movies aimed at the 45-and-up demographic (Grandma, I’ll See You in My Dreams, Far From the Madding Crowd, The Second Best Exotic Annuity for Aging Stars) performed well, but many indies aimed at younger audiences—Sundance successes like The Diary of a Teenage Girl, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, and 99 Homes—did alarmingly tepid business. Younger moviegoers, raised knowing they can see everything eventually, are staying home and complacently destroying the theatrical market for the kind of movies they profess to want. (You don’t get to complain that indie movies look like television if you only watch indie movies on television. Also, television is good, and to the extent that movies like Andrew Bujalski’s wonderful rom-com Results have an affinity with TV, it resides in their sharp writing and characterization; I’d happily trade a few movie houses full of empty-headed swooshy-camera “pure cinema” for more of that.)

Right now, I am willing to celebrate, or at least tolerate, almost anything that gets you to an actual theater. (Except Daddy’s Home.) Which is why I applaud the you’ve-gotta-see-this-in-70-mm gimmick of The Hateful Eight’s retro-roadshow release. I care less about film versus digital projection than any cinephile I know, but the flourish and showmanship of using an overture and intermission (an act break that actually enhances the storytelling and gives people a few minutes to gather their wits) greatly appealed to me. Admittedly, I have a soft spot for the bloated ’60s epics that used to be presented that way. (I just rewatched Doctor Zhivago; I still think it’s pretty dreadful, but I’ll probably never stop giving it one more chance.) But beyond that, I appreciate any attempt to make the experience of moviegoing feel essential, especially one that doesn’t involve 3-D glasses.

But it wasn’t just the packaging. I also liked the movie, about which, to quote one of the most egregious Oscar speeches of all time, I have something to say and a burning need to say it! I’m not going to try to talk anyone who didn’t like Inglourious Basterds or Django Unchained into hopping on board the Tarantino train with The Hateful Eight. But I would like to make the case that this, the third of Tarantino’s consecutive adventures in American history, should not be the breaker of the camel’s back; it’s the wrong movie to use to walk away from him. Dana, you called it a “revenge fantasy,” a label I would certainly apply to the happy-ending rewrites of World War II and the Reconstruction era in his previous two movies. But one thing I admired about The Hateful Eight is its discomfort with that model. In fact, the flashback scene that ends the first act—the horror story Samuel Jackson tells to Bruce Dern—is explicitly framed as a revenge-fantasy narrative that may or may not have even happened; that scene may well be Jackson’s shrewd guess at Dern’s creepy nightmare of what a black man’s revenge fantasy might be. In this movie, fantasies (the letter that’s a central plot element may be another) have their uses, and Jackson’s definitely accomplishes its goal, but they also have their limitations.

I applaud the fact that Tarantino is tying himself into knots on this movie. It seems to me that he’s wrestling with race rather than posturing about it, and also wrestling, in a welcome way, with gender. For my money, Jennifer Jason Leigh is, with due respect to her predecessors, the first truly great actress to have a major part in a Tarantino film, and as eager as the other characters are to use her as a punching bag, she’s more than that; she’s a skilled, tough player in this game of elimination who uses every card she holds (or can make the other players think she holds). (Also, there are 10 characters, so which two aren’t hateful is open for debate, and may include her.) Not to give anything away, but I don’t think it’s an accident that in the final shots we see of Daisy she is framed first as a witch (the Wizard of Oz shoutout shot of her shoes) and then as an angel (with snowshoes behind her positioned as her wings). I found her fascinating, and the movie as well; to me it seemed not a dead end for its writer-director, but a step—as steeped as it is in the language of older movies—toward something new.

Just as Amy wonders whether critics were politically soft on the good-causey Danish Girl, I wonder if some have been politically punitive about the “problematic” Hateful Eight. Then again, maybe they just hated it; I’m trying to stick to the principle of never impugning the motives of people who disagree with me about a film.

What have I left dangling from your opening salvos? I am pro-Spy, pro-McCarthy (Melissa and Tom), pro–Star Wars, as pro-Carol as anyone not named David Ehrlich could possibly be, and adamantly pro-Creed. Amy, I am deeply offended, by which I mean secretly delighted, that you think enough testosterone courses through my male-critic aesthetic to have clouded my judgment about Ryan Coogler’s thoughtful, savvy, fluid, heartfelt, emotional relaunch of a franchise so dormant that six months ago we wouldn’t have even called it a franchise! I was moved to see this story, which began 39 years ago as a narrative about a white underdog going up against a cocky black overlord, pass into the hands of a breathtakingly talented black director and an equally talented black star (and, by the way, a black co-writer, and women filling the roles of DP, editor, production designer, and costume designer), and honor the original narrative while turning it inside out. I loved it, and I bow to nobody in my boredom with guy stuff!

Also, yes, I did see Tangerine, and its absence from my personal Top 12 list notwithstanding, I liked it very much as a rude, screechy, and tender portrait of two hot messes. I will even posit that it’s good enough so that we don’t have to talk about the fact that it was shot on an iPhone, which feels to me like this year’s indie equivalent of “Leonardo DiCaprio had to eat gross things and be outside a lot.” Enough of that extratextual A-for-effort stuff! (Also, if any of you have been thinking, Oh no, he’s going to be nice about every movie this year, just ask me about The Revenant.) And with that, I pass the baton, or, to echo Tangerine’s sweetest and most lasting moment, the wig, back to Dana.

Mark

Read the previous entry | Read the next entry

To get each new entry in this year’s Slate Movie Club in your inbox, enter your email address below: