Have you seen the newest Michael Mann film? No, not the one about the ex-con who falls in love as he tries to take a final score—you’re thinking of Heat. Nope, also not the one about the ex-con who falls in love as he tries to take a final score—that was Public Enemies. I can see why you’re confused, but this is certainly not the one about the ex-con who falls in love as he tries to take a final score—that was Thief. I’m talking about the one that arrives in theaters Friday, about an ex-con who falls in love as he tries to take a final score. It’s called Blackhat. Have you seen that film before?

I’ve seen it, and all the others, too. I’ve just completed an audacious and ultimately stupefying project: to watch every film and TV show that Michael Mann has ever made. This was not an easy task. In the months since I set out to reach this goal, I’ve had to track down video of long-forgotten television shows. (Remember Vega$, the rambunctious private-detective dramedy from the ’70s? I didn’t.) I’ve logged many hours in the “Scholars Room” of Manhattan’s Paley Center for Media, peering at a grainy monitor and taking notes on episodes of Robbery Homicide Division, a short-lived police procedural from 2002. I’ve purchased an expensive region-2 DVD of a TV movie called The Jericho Mile from an online retailer who also sells a wide array of dildos. I’ve downloaded Russian-language dubs of Drug Wars: The Cocaine Cartel, a cruddy miniseries that aired in 1992. I’ve even stopped by in person at Mann’s production office in Los Angeles, for a private screening of a documentary short he made more than 40 years ago. (For a detailed description of how I set the rules for this project—which shows to watch and which to skip—see my ranking of the work.)

Here’s what I’ve learned: Michael Mann is caught in a time loop. His characters often find themselves in the same predicament: They’re running out of time; they’ve lost their time, got no time; they’re doing time; time’s doing them. They’re taximeters running in reverse; they’re needles that start at zero and go the other way. The value of their asses is declining. They’re “double blank.” Life is short. One last score and then they’ll quit. Should they be doin’ something else? Dog, they don’t know how to do anything else.

Neither does Mann. He’s as seasoned in his filmmaking as the guys in Heat, who time their armored-car heist to the second with a stopwatch; or the guys in Public Enemies, who time their bank heist to the second with a stopwatch; or the guys in Straight Time who time their jewelry heist to the second with a stopwatch. (N.B. Mann helped to write Straight Time but did not get a credit.) That is to say, he’s as exacting and effective as his heroes, a stickler on the set who rules over every aspect of his movies like an ace criminal. At a recent Q&A in New York City, Tom Noonan, who appeared in both Heat and Manhunter, called Mann a “Napoleon,” who once fired his entire art department for screwing up a minor prop. The director also made Joan Allen cry: “What the fuck?” he’d say, according to Noonan, when they finished up a take. “You think anyone is gonna believe this shit?” (“Maybe I’m exaggerating,” Noonan added. “It’s been a while.”)

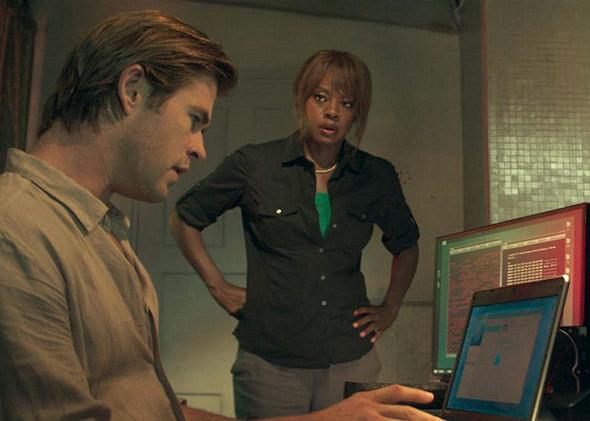

Yet no matter how perfectly he might pull off a job—and let’s face it, Heat comes pretty close—Mann keeps gunning for another, better version of the same. Blackhat is the latest in this spree of moviemaking. This go-round the ex-con is a hacker—Chris Hemsworth as a nerd-turned-hunk in shades and stubble, with wisps of hair that flutter down to frame his jaw. He’s been released from jail on the condition that he helps to catch a rival, evil to the core, who’s caused a meltdown in a nuclear power plant and ginned up a run on soy futures. Will Hemsworth get inside the villain’s code and suss out his secret motives? Will a gorgeous systems engineer who works with Hemsworth find a way to hack into his heart?

Courtesy of Universal Pictures

I don’t want to make Blackhat sound ridiculous—it’s only intermittently so; the rest meets the baseline standard for Michael Mann productions. It’s upscale, modish and shot through with icicles of beauty. But in many ways the biggest hack you’ll find in this cyber-thriller is Michael Mann himself. That’s not a criticism; it’s a fact. Perhaps no director of such renown has been so flagrant in his copy-pasting of old material—from minor flourishes to major plot points, and everything in between. Yet his brazen hackery is not a bug, exactly, but a central feature of the work. Michael Mann repeats himself in movies in the same way that Ray Allen repeats himself at taking threes. He’s a professional. He’s a genius of his chosen craft.

Professionalism can wear a person down, however, especially when that person tries to watch more than a dozen movies in a row, and then a spate of TV shows and commercials. That person might even go a little crazy from the endless echoes in his head—streetlights reflected on the shiny hoods of cars, men staring at the ocean, blue lights, white supremacists, needy women. The reverberations even run to the dialogue: Actors say the phrase, “Time is luck,” in Heat, Manhunter, and Miami Vice. (It’s also in the script for Collateral.) “When they walk through that door, they’re going to get the surprise of a lifetime!” blurts Al Pacino’s character in Heat, delivering a line that turns up in an episode of Crime Story, and an episode of Robbery Homicide Division, and in the TV movie L.A. Takedown.

Much of the script for Heat is lifted verbatim, in fact, from L.A. Takedown. Mann had been working on that project since the late-1970s, and by 1989, he’d shot it as a pilot for a cop show called “Hanna.” Instead of De Niro and Pacino in the leading roles, Mann had a pair of second-rate Don Johnsons, dreamboat types who couldn’t act, in suits with shoulder pads. The movie comes off like a bunch of USC film students running scenes for a school project. It’s all the words from Heat, without any of the drama:

By that point in his career, critics had gotten tired of Mann’s style. Thief, his breakout theatrical debut in 1981, had earned him plaudits far and wide. (So had The Jericho Mile, his Emmy-winning TV movie from 1979.) Variety called Mann “a potent triple threat” for producing, writing, and directing. Roger Ebert said that Thief was “one of the most intelligent thrillers I’ve seen.” But the director moved on from this early triumph in what he called “stylized realism” into what I’ve come to think of as his High-’80s period. His new mode, much more stylized and somewhat less realistic, reached its apogee in Miami Vice, a show supposedly conceived in a two-word pitch scribbled on a piece of paper: “MTV cops.” I’m partial to this phase of Mann’s career, where everyone wore skinny ties and stood in front of colored walls, and gloss could be an end unto itself. But the surface chic could be overbearing, too, and at times ridiculous, as in his ill-conceived Holocaust-horror flick from 1983, The Keep. That movie starts off with an icy-hot Nazi on patrol, Sonny Crockett ca. 1941, lighting up a cigarette as his truck drives through the rain. From there it’s glowing shafts of light, exploding heads, and bodies ripped in half—all presented in a solemn, art-house tone. (Naturally, The Keep does have some superfans online.)

Manhunter, his 1986 serial-killer film, met the same critique—a “Miami-Vice clone,” wrote a critic for the Associated Press. (It didn’t help that Mann brought in several actors from the TV show.) But Mann stood by his taste for surfaces: “I could have made a very gritty, very realistic movie that would have had a tremendous amount of power,” he told the Miami Herald. “My whole strategy about the form of the film was … to distance the film from the audience by making it glossy, so that it would appear to be up there on the screen, and not coming at you.”

L.A. Takedown, the high-gloss premake of Heat, may have been the turning point. From there Mann drifted from the pretty to the gritty, and a set of films that would restore his standing as an artist. The movement started with The Last of the Mohicans—a visually impressive but somewhat cartoonish take on the French and Indian War—and continued through three excellent films in which his trademark sense of style helped intensify, instead of overwhelm, the content: Heat, The Insider, and Ali. And in 2002, he executive-produce the underrated TV show Robbery Homicide Division. (Tom Sizemore, the star of RHD and a key player in Heat, is my all-time favorite incarnation of the Mann’s-man archetype: A tough guy with long eyelashes who seems always on the verge of a coke-fueled meltdown.)

But even in this high-end phase of Michael Mann, you can’t escape his insistent, maddening repetition. Take Episode 9 of Robbery Homicide Division, “Life Is Dust,” in which Sizemore’s Lt. Sam Cole infiltrates a gang of Vietnamese arms dealers, only to fall in love with the crime boss’s wife. That’s more or less the plot of Miami Vice, the 2006 movie version, only now it’s Colin Farrell as Sonny Crocket, and Gong Li as the half-Chinese love interest and wife of a Colombian drug lord. The stories overlap throughout, even sharing lines of dialogue. Just one example: Both include a scene in which the undercover white guy takes a shower with his Asian boo, then ends the sex by talking business.

As I made my way throughout his oeuvre, Mann’s penchant for recycling old material often struck me as a weakness. Films I’d loved when they came out now seemed like second helpings. It was as if he’d spent all his good ideas and fired off his favorite bits of dialogue. But having seen the work in total, I think that I was off the mark. Mann isn’t out of ammunition; he’s just shooting and reshooting his very best materiel.

Even when he leaves crime-action films behind, Mann’s method brings him back to where he started. In his period pieces, he’s always been fanatically “authentic.” He films in original locations, such as the run-down jail in Crown Point, Indiana (where John Dillinger escaped in 1934), or the Little Bohemia Lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin (where Dillinger survived a shootout with the feds just six weeks later). For The Last of the Mohicans, Mann had 1,200 knife sheaths woven from porcupine quills in the patterns of specific tribes and made Daniel Day-Lewis learn to track and skin animals. Yet for all this effort to find time and place and character, Mann has never quite escaped his own specific history, a child of working-class Chicago, in a neighborhood where few kids went on to college.

That’s the strand that holds Mann’s work together, drawn from his primeval source: old-school cops and robbers in the place where he grew up. To make Thief feel authentic, Mann relied on two real-life figures from Chicago: a former jewel thief named John Santucci and a cop named Chuck Adamson. (Both had parts in the film as well.) Adamson inspired characters in both Crime Story and Heat, and did as much as anyone to shape Mann’s treatment of the genre. Time and time again the director has gone back to the lingo that he learned from these Chicago pals, their codes of honor and their way of life. He’s reapplied them to the 1930s and the 1960s and the 1980s and the 2010s, to Los Angeles, Miami, New York City, and Jakarta. Dennis Farina, a Chicago cop who worked with Adamson, was for many years the gruff, mustachioed face of this aesthetic. He made a brief appearance in Thief, then quit the force to join the cast of Manhunter and brought his flinty Inland North to Mann’s glistening TV shows: Miami Vice, Crime Story, Drug Wars: The Cocaine Cartel, and Luck. Even Chris Hemsworth, as an MIT-trained hacker in Blackhat, ends up talking like a Windy City gangster from half a century ago: “He knows he’s gonna bring down heat,” he tells his partner, as if channeling Farina.

That same old-school sensibility may explain the role that women play throughout his films. They often serve as an Achilles’ heel for the master criminal, not because of what they do (which isn’t much) but what they represent: a breakdown of discipline, a value other than the score. “You can see what color I am,” says Tom Sizemore’s character in an episode of Robbery Homicide Division. “Green. As in money. M-O-N-E-Y. I have one rule: Do not waste my time.” He’s like so many men in Mann, he’s only in it for the action and the juice … until love gets in the way.

Click here for Daniel Engber’s ranking of Michael Mann’s films.

“I think he’s so fucking ugly,” Mann once said of his friend Farina, but “Dennis is, I hear, attractive to women.” That’s the secret of Mann’s work, I think, and his most beguiling achievement. The ugliness in his films stands in for what’s honest and authentic—but it’s often just a mask, a surface of its own. And the beauty in his films, seemingly a surface quality, seeps into their roots. He’s a stylized realist, but even after so much repetition it’s hard to tell which parts are which.