In the second episode of the seventh season of the fourth Star Trek television series, Icheb, an alien teenage civilian who’s been living aboard a Federation vessel for several months after having been rescued from both the Borg and abusive parents, issues a plaintive cry: “Isn’t that what people on this ship do? They help each other?”

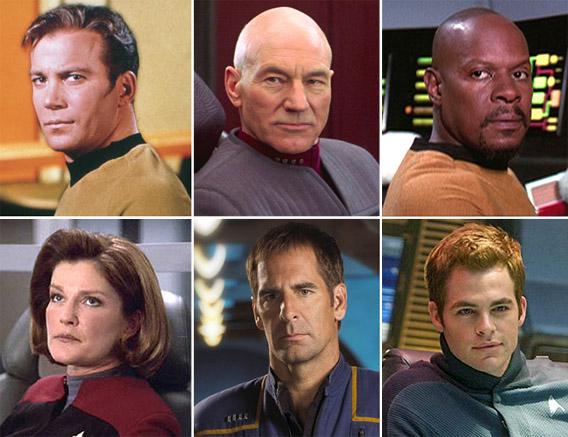

It’s an unremarkable episode in one of the worse iterations of the franchise, but the need for an isolated and impressionable young man to offer his assessment of the situation brought a certain clarity to the whole project. The Star Trek oeuvre is immense. Five television series adding up to many hundreds of episodes plus 11 films (so far) and untold novels, comics, and other licensed material. Even restricting myself to TV and movies, it’s an awful lot of material to process. But angsty teen Icheb hit the nail on the head there, plaintively begging Captain Katherine Janeway and the ship’s holographic doctor to let him undergo a dangerous medical procedure that just might save the life of another ex-Borg on the ship who has served as his mentor. They let him go forward, because he’s right: People on the Federation Starship Voyager do try to help each other, as did the people on the various other vessels named Enterprise and even the staff of the Deep Space Nine station.

Starfleet officers help people. And God bless them for it.

The standard line among Trek apologists is that the franchise is not just a lot of sci-fi nonsense but a meaningful exploration of what it means to be human. And among Trek’s kaleidoscope of Vulcans and androids and holograms and shapeshifters, this is a core concern. But Trek has a very particular take on what it means to be human. Part of what it means, the franchise teaches us, is participating in an ongoing progressive project of building a utopian society. Even though the bulk of Trek comes from the ’90s, the franchise launched in the mid-’60s, and the now-anachronistic spirit of midcentury optimism has remained at the heart of the franchise throughout. It’s a big part of what makes Trek great.

* * *

Nicholas Meyer, writer and director of the best Star Trek movies, once wrote that “at its absolute worst, Star Trek is a plaid-pants, golf-course Republican version of the future where white men and American values always predominate (despite blatant tokenism), and gunboat diplomacy carries the day.” And perhaps that’s true—when the show was at its worst. But at its best, the Original Series reflected not plaid-pants arrogance but Great Society optimism.

To dismiss Kirk’s multiracial crew as blatant tokenism seems unfair, given that it piloted the Enterprise at a time when legally entrenched segregation was a subject of ongoing political controversy. Nichelle Nichols’ Lieutenant Uhura is a black woman whose name means “freedom” in Swahili and who served as an officer aboard a starship at a time—back on Earth, I mean—when there were no female astronauts or military officers and black characters on television were more likely to be maids than professionals. Equally striking, given the political context of its era, is Ensign Pavel Chekov, navigator and proud Russian nationalist. The show asked audiences to imagine a seemingly amicable resolution of the Cold War.

More important, perhaps, than these dollops of diversity, is the very nature of Kirk’s five-year mission: “To explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.” The line is so famous today as to be a cliché, but it’s striking when you take a second to really think about it. The Federation, which our beloved crew serves, is engaged in something like a cold war with the Klingon Empire. But its premiere starship is not a military vessel and has no sharply defined political agenda. Kirk establishes diplomatic relations with new species and tries to play a constructive role in the galaxy, but he’s not there to open new markets to Federation goods or to assist one side or another in proxy wars. The “American values” that triumph in the Star Trek universe are the values that united liberals before the Tet Offensive and the riots in American cities and assassinations and Watergate. And though the message of peace, progress, and tolerance may seem corny today, I happen to think those are still good ideas.

Granted, when you judge it purely as television, the Original Series is a bit weak. (There aren’t many 45-year-old television dramas that hold up well.) Continuity is a mess; the sets look cheap; the acting is hammy. The show was a commercial failure and died after three seasons. But it was resurrected in cinematic form, first with Star Trek: The Motion Picture—which was forgettable, really, but made enough money to spawn an excellent sequel and two solid follow-ups after that.

The films showed the world that bigger production budgets and better special effects could make a dramatic difference. The new-look Klingons, with real alien makeup instead of silly goatees and bronzer, were a huge step up. Star Trek II reprised the Original Series’ best villain, and the light-comedy time-travel caper Star Trek IV showed that the franchise’s signature political concerns could be updated for the 1980s. (Kirk and company voyage to the late 20th century to try to forestall a future disaster caused by the extinction of Earth’s whale population.) Having demonstrated to Paramount that there was a lucrative market for quality Trek content, the studio then began to work on the best and most successful Trek of all, Star Trek: The Next Generation.

* * *

Though technically a spinoff or sequel to the original show, TNG is in most respects the “real” Star Trek. It ran for much longer—seven seasons—and obtained ratings never seen before or since for a series distributed via syndication rather than over a national broadcast network. With proper budgets and a determination to serve the needs of a large built-in fanbase, it’s TNG that gave real shape to the Trek mythos. It’s also simply one of the finest dramas from the one-off era of television, offering far deeper characters and a much richer world than the police procedurals and doctor shows that dominated the medium.

TNG also demonstrates that in the Trek universe, not only will the future be better than the present, but life will continue to improve as time marches on. There’s no Russian on Jean-Luc Picard’s bridge, but there is a Klingon—the token of a new spirit of friendship between the Federation and the Empire (the origins of which are explored in Star Trek VI). The cast also includes a blind man whose sight has been restored by technology and a sentient android with human rights and a Starfleet commission. The team’s “continuing mission” has the same broad and peaceful mandate as Kirk’s, and their conduct is precisely the opposite of gunboat diplomacy.

There is one problem, though: The new ship has been equipped with a holodeck, an entertainment device that manages to risk the ship’s destruction with surprising frequency and that proves a dangerous tool in the hands of lazy writers.

Typically, Picard and the Enterprise-D face problems—Wesley’s been sentenced to death, Riker is held prisoner on a pre-warp planet, Troi’s mom is coming to visit, Tasha Yar is being pressed into a forced marriage—that could be easily solved by photon torpedoes or a commando squad, and the real dilemma is how to get out of the jam without resorting to violence.* We also see the practical operation of a post-scarcity socialist economy. Picard explains in Star Trek: First Contact that “money doesn’t exist in the 24th century,” when “the acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives.” Instead, “we work to better ourselves and the rest of humanity.”

And it could hardly be otherwise. Consider the miraculous technology of the replicator—a machine that can seemingly create anything out of thin air, based on rudimentary raw materials plus energy. When computers and energy can substitute for productive human labor, either the energy supply will be controlled democratically for Federation-style liberal socialism, or else it will fall into the hands of some narrow clique and give us the fascistic authoritarianism of the Klingons, the Romulans, or the Cardassians. Under the circumstances, nothing resembling capitalism as we know it could survive. As Marx wrote in his Critique of the Gotha Program, the material prosperity made possible by ever-better technology is the necessary precursor to an economic system ruled by the principle, “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” And that’s the principle the Federation lives by.

* * *

The Next Generation was so successful it spurred two spinoffs that shared its 24th-century setting. Star Trek: Deep Space 9 launched while TNG was still on the air and physically set itself on the very edge of the federation. Star Trek: Voyager came a few years later, after TNG departed but overlapped with DS9 for several years. In order to avoid getting excessively tangled up in DS9’s plot arcs, Voyager sent its crew all the way to the other end of the galaxy, marooned by a space accident in the remote Delta Quadrant, a decades-long journey from home.

The two shows were quite different in tone, structure—and quality. DS9 is the most narratively ambitious Trek of all; it even managed to pull off a good holodeck episode (“It’s Only a Paper Moon”). Voyager, on the other hand, was a deliberate and somewhat perverse effort to recapture the spirit of the (lest we forget) ultimately unsuccessful Original Series. Except this time, the characters were less interesting.

And both shows suffer for having been filmed during the awkward teenage years of television drama. Modern TV features a fairly sharp divide between shows structured around long plot arcs (Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones) and those built as a series of one-offs (CSI). But in the late ’90s, things were different. DS9, like Buffy and The X-Files, flits back and forth between a big-picture story and alien-of-the-week one-shots. This makes for disconcerting binge-watching. The sustained 10-episode narrative that concludes the series is the best run of Trek that’s ever been made. But it comes after years’ worth of television in which the grand clash between the Federation and the Dominion is regularly interrupted. Some of these one-offs—those set in the Mirror Universe especially—are fun. But others are dreadful (Sisko has to train his crew to beat a bunch of arrogant Vulcans at baseball) or simply bizarre (Sisko fights racism in the sci-fi industry of the 1950s).

Rather than build on the most promising elements of DS9’s narrative ambition, Voyager essentially retreats from them. The location in the Delta Quadrant allowed the writers to dream up brand-new alien races. Even better than that, the Borg—Trek fandom’s favorite rarely seen foe—lived in the Delta Quadrant and could be featured frequently. But the plotting is very much alien-of-the-week. Over the course of its seven-season run, the ship never feels like it’s actually making progress. By the penultimate episode, the crew is still stuck decades from home—then it’s rescued in the finale by a deus ex machina. That both those episodes are actually quite good only underscores the larger tragedy of the series: Thought through a bit better, it could have been excellent.

DS9, on the other hand, is anchored by a dangling plot thread from TNG: The planet Bajor has been subject to brutal occupation by the militaristic Cardassian Empire, which is simultaneously involved in a territorial dispute with the Federation. Just before DS9 begins, the Federation and Cardassia reach a peace deal that involves freedom for Bajor in exchange for the handover of some Federation colonies to the Cardassians. The show is set on a Federation station orbiting the newly independent planet, adjacent to 1) the hostile Cardassians and 2) a band of ex-Federation rebels who refuse to have their homes handed over to the enemy. Even worse, the station turns out to be right at the mouth of a wormhole that leads to the distant Gamma Quadrant and eventually becomes the entry point for an invasion of hostile shapeshifters.

Partly because of that premise—and partly because one of the major creative forces behind it, Ronald Moore, went on to reboot Battlestar Galactica—DS9 is often considered the “dark” Star Trek. Meanwhile, many fans lambaste Captain Janeway of Voyager as a dopey idealist. In truth, though, the core themes of progressive optimism run through both series.

On DS9, the coming together of Bajoran collaborators and resistance fighters is a key theme, as is sympathy for individual Cardassians. There’s also a focus on the importance of maintaining civil liberties even in the face of very real security threats. The war is devastating to many planets but ultimately serves as an engine of social progress that spurs reform in both the Cardassian and Klingon empires. In a two-part episode detached from the main narrative thread, Sisko and two crew members travel back to early-21st-century Earth, where they help shake the powers that be out of their complacency about mass unemployment. Even the Ferengi come around by the end and start adopting gender equality and a welfare state. The social and political stakes were generally higher and more explicit on DS9 than on either of the Enterprise-based shows—but sunny optimism still reigns.

And when it was at its best, the core Trek values ring through on Voyager, too, even if it was hobbled from the start by ill-conceived characters. The show made a statement with its lead, Kate Mulgrew’s Captain Katherine Janeway, a woman finally given command of the ship and leading it with quiet workaday competence and moral rectitude. Janeway’s crew is the most diverse ever featured. The writers just forgot to make them interesting. B’Elanna Torres reduces the Klingon character to nothing more than a bad temper while Tuvok devalues Vulcan logic into little more than sneering condescension. First Officer Chakotay progresses from non-entity to flat, Native American stereotype who occasionally solves problems with spirit visions. (There are no practicing Christians, Muslims, or Jews remaining in this time period, but Native American culture seems oddly frozen in amber.) Harry Kim is perhaps the least interesting character in the entire franchise.

Over time, the show improves considerably. Boring characters are sidelined. The Emergency Medical Hologram unexpectedly pressed into full-time service starts playing a larger and larger role. Seven of Nine joins the cast. Lieutenant Reginald Barclay, a neurotic genius featured on a couple of TNG episodes, is brought into the action as a lead scientist in the Alpha Quadrant working to get in touch with Voyager. But to the bitter end the series offers far too many holodeck episodes and can never quite shake its legacy as a misguided venture.

* * *

After Voyager’s stint ended in a blaze of low ratings, Paramount decided to reinvigorate the franchise by shifting back in time. Telling the story of the first starship Enterprise—humanity’s first ship capable of traveling at Warp 5—was a way, they thought, of stripping the series of technobabble and gimmicks and putting the focus back where it belongs: on the sheer adventure of space travel.

It’s a neat idea. But throughout its abbreviated run, Enterprise is a show torn between two concepts. On the one hand, it’s a prequel, offering further explorations of the origins of the Trek world that fans have come to know and love. We see the troubled-but-beneficial evolution of the human-Vulcan alliance and the formation of the United Federation of planets. We learn how humans got off on the wrong foot with Klingons and get to enjoy a humorous effort to provide an in-universe explanation for the change in makeup. We come to understand the origins of the Prime Directive as meddling in the culture of a three-gendered species that came to a sad end. We see the buggy, 1.0 version of the Universal Translator, a Starfleet crew that’s not comfortable with transporter technology, the “protein resequencer” (an early precursor of the replicator), and other fun Easter eggs.

But going back in time was supposed to cut the show off from all that fanboy baggage. In fact, displacing the narrative backward in time only exacerbated such tendencies. If Starfleet crews had been participating in a Temporal Cold War dating back to the maiden voyage of the first Enterprise, how come nobody mentioned this in other series’ extensive time explorations? How compelling is a season-long plot about saving Earth from a Xindi superweapon supposed to be when we’ve already seen many shows set in the future, with Earth alive and well? Low ratings led to the show’s cancellation before its planned end—surely not what the producers had in mind when they spoke of returning to the franchise’s roots.

Yet for all the series’ flaws, its fourth season, at least, is must-viewing for fans of the earlier, better outings. Here we learn, at last, of the actual origins of the Federation and how it came to be centered on Earth despite humanity’s relatively late arrival on the warp-travel scene. It’s a multilayered tale, involving political upheaval on Vulcan (“Kir’Shara”), the Enterprise’s mediation between two warring races (“Babel One”), multi-species cooperation against the Romulans (“United,” “The Aenar”), and the eventual facing down of xenophobic elements in Earth politics ("Demons,” “Terra Prime”).* It underscores the idea that the greatest power in the Alpha Quadrant was forged, from the beginning, through missions of peace and diplomacy, not conquest.

* * *

And then came J.J. Abrams’ reboot film, Star Trek. With the TNG films showing waning box-office appeal, Paramount took the dramatic step of allowing a fresh creative team to simply wipe the entire continuity clean. As a serious fan, watching it was both thrilling and terrifying. Abrams gave us a nice space-adventure romp that, after years of failure, had clear mainstream appeal. But the price was high. Time travel—like all the other technologies of the future—could be terrifying in theory but in practice always ended benignly. Now an entire universe—all the adventures of Kirk and Picard and Sisko and Janeway and the rest—was wiped out for the convenience of a director who, by his own account, is not a dedicated fan of the franchise. And while the movie was great fun, it has no particular connection to Trek’s distinctive themes.

And besides, even if the commercially successful films saved the franchise, Trek’s true home has always been television. The cinema demands what Abrams delivered: action, suspense, drama. But it’s less well-suited to the signature thematic project of the franchise: to depict, in a sustained way, life in a better tomorrow.

Utopia requires moments of peace and quiet. Random episodes about an Android bonding with his cat, say, or a bartender’s schemes to increase his profits. You can’t make a lucrative sci-fi flick about people sitting around in a conference room debating options for resolving the situation peacefully—but something that can be accurately teased as primarily consisting of thrilling space battles is not the real Star Trek. A bunch of friendly folks using advanced technology to help people? That can only be profitable, I suspect, on the small screen.

So I hope the success of Abrams’ movies paves the way for the triumphant televisual return that Trek richly deserves. And I hope that this time they do it right: Put it on cable, where niche entertainment can thrive, and give us sustained plot arcs that stretch across short cable seasons. The highest-rated Mad Men episode ever, the Season 5 premiere, drew 3.5 million viewers—a mark that even the failed Enterprise series beat in the majority of its episodes. It’s a scandal that the golden age of niche television is passing us by without any representation from the franchise that practically invented niche television.

I will continue to dream, at least, that Abrams’ interstellar action movies will bring the real Star Trek back to life. The one in which phaser volleys rarely solve anything, the timeline is always restored, and a ship and its crew wander more or less aimlessly through space to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where—well, where a few men (and women) have now gone before but where we want them to keep going, again and again.

*Correction, May 15, 2013: This article originally referred to proton torpedoes rather than photon torpedoes. An earlier version of the article also said the Enterprise episode “Terra Nova” was about xenophobia in Earth politics. In fact, “Terra Nova” is about the fate of humanity’s first deep space colony. The episode about xenophobia is “Terra Prime.”