The new season of Orange Is the New Black picks up almost exactly where Season 4 left off, with Daya (Dascha Polanco) standing over a sadistic guard and holding a loaded gun as a mob of women clamor for her to pull the trigger. The lack of any kind of time-jump here is reassuring; Season 4 ended with the tragic death of Poussey (Samira Wiley), who was choked by a guard during what was supposed to be a peaceful protest, and it’s smart that the show doesn’t try to zip past her death, instead making that one event the catalyst for the entire season’s plot: a massive prisoner uprising that not only raises the stakes but alters the very structure of the show. Previous seasons of Orange of the New Black have focused on the effects of introducing new variables into Litchfield’s delicate ecosystem—whether that’s a new O.G., the privatization of the prison, or an influx of new inmates that upsets the racial status quo. Now Poussey’s death irreversibly alters the dynamic, most noticeably by putting the inmates in charge for a change. What follows is like a tragicomic replay of the Stanford Prison Experiment, the famous 1971 psychological study in which 24 college students were sorted into groups of “guards” and “prisoners.” What happens when the captives become the captors?

All of Season 5 takes place during the three-day riot, a major structural change for a show that is used to developing plots and characters over the course of months at a time. Some characters, mostly the comic relief, suffer for this structural shift: It’s one thing to watch Leanne and Angie get high and cause trouble for a single episode, but it’s another to watch them bumble around the prison in a drugged haze for 13 straight hours. Flaca and Maritza (now known as Flaritza) fare a little better as newly minted YouTube stars who absurdly continue to give beauty tutorials even as Litchfield is gradually surrounded by MCC employees, police, media, and later, friends and families of the inmates, all waiting to see how the standoff will end.

While the show’s shorter time frame has led some to label it a “13-hour bottle episode,” the barricaded inmates are, ironically, less contained than ever. Now with unfettered access to phones and internet, Litchfield is no longer the isolated place it once was, a development that allows for a number of new storylines. For one, Red (Kate Mulgrew) is obsessed with luring Piscatella, the tyrannical guard on whose watch the prison became a true nightmare, back inside Litchfield’s walls so she can get revenge on him for making her life miserable. Meanwhile, Taystee (Danielle Brooks, in her best performance yet) wants to use this newfound connection to the outside world to try to get justice for Poussey. (It is both hilarious and heartbreaking when the inmates’ initial video, in which they force the warden to say Poussey’s name, is upstaged by a meme of Black Cindy drinking an iced coffee in the background.) The women of Litchfield, and Taystee in particular, finally have a real chance to reform the prison system, not only for the Pousseys of the world but for them all, with a list of demands that include health care and education reform in addition to better snacks. The negotiations that follow result in some fascinating debates between Taystee, Caputo, and blast-from-the-past Figueroa about the state of the prison-industrial complex and their own different levels of complicity in it.

Netflix

Season 5 is all over the map in terms of tone, which is nothing new for Orange Is the New Black. The first half of the season plays up the comedy of the marginally improved conditions inside the prison walls—a pop-up café that unites the skinheads and the Latinas is a nice touch—while the second half reckons with just how dark the inmates’ situation still is. The show demonstrates a willingness to explore some pretty deep and sometimes uncomfortable philosophical territory, which might be best exemplified by the thought experiment that Piper poses in the eighth episode: If a train is heading for five people tied to the tracks, do you throw the switch to divert the train even if that means it will hit someone else? (Interestingly, this exact dilemma was recently explored in another Netflix original series.) The show poses some fundamental questions about morality in between all the scatological humor and jokes about severed fingertips: Should the prisoners make a deal even if it means they won’t get everything they want? Is it right to give up one of their own to protect the rest? And is there any moral justification in revenge when the perpetrator is so clearly evil?

The boogeyman of this season of OITNB is supposed to be Piscatella, who is re-introduced to the narrative with a series of horror movie and slasher flick tropes that aren’t all that much funnier for being winked at. Unlike other villains on the show, there’s very little in Piscatella’s backstory, shown in flashbacks, that can convincingly redeem or even complicate his present actions; even with a tragic past, he is one sick dude, which makes him feel a little lacking as a Big Bad.

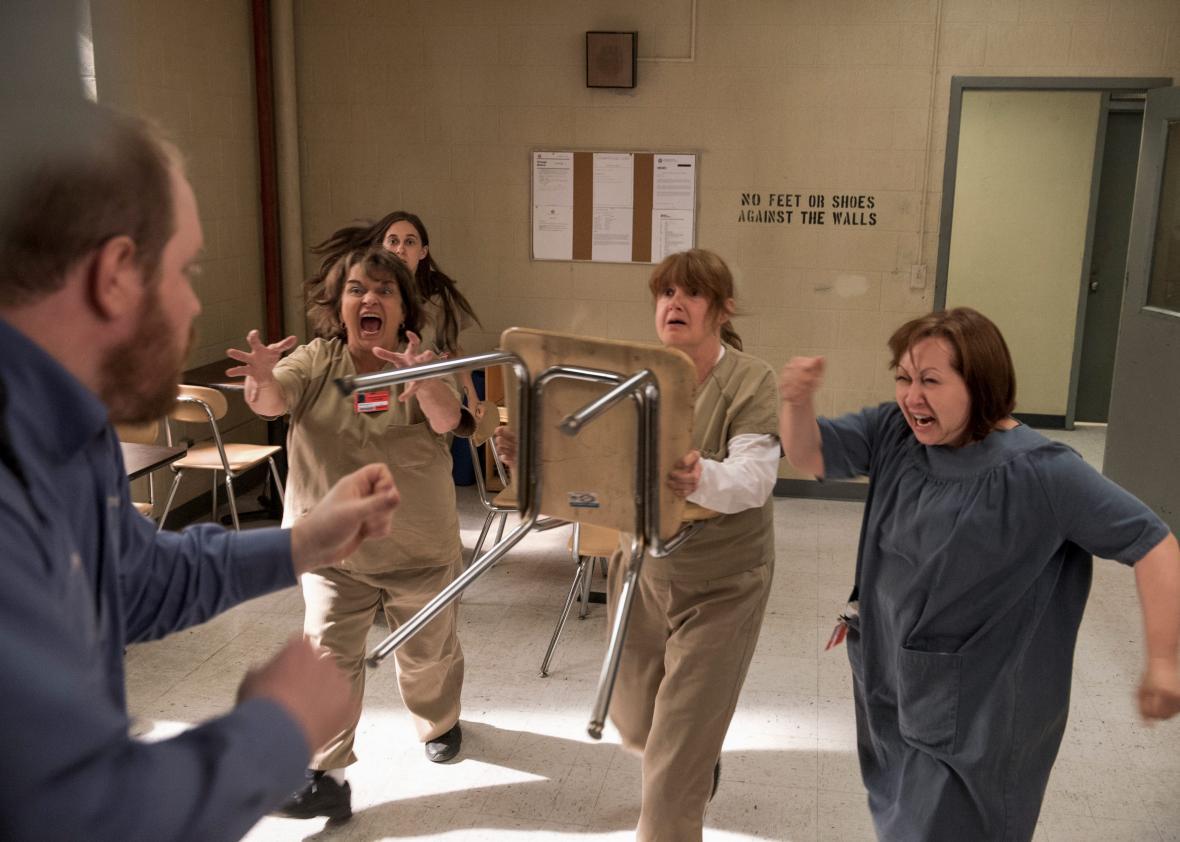

But maybe that’s because Piscatella isn’t the real enemy—and neither, really, is the SWAT team assembling outside, even while they explicitly remind us that prison riots never end well. The villain, as always, is the prison-industrial complex itself, and that’s plenty scary. With the roles reversed, the women of Litchfield torment their former guards, relishing the opportunity to turn the tables and give them a taste of the public humiliation and sexual harassment that comes with being incarcerated, even sending them to “solitary confinement” by locking them up in outhouses in the yard. It’s funny to see the guards forced, at gunpoint, to put on a talent show, but it’s terrifying, too. Orange Is the New Black has already smartly demonstrated how prisons can attract psychopaths, like Pornstache or Humps, and corrupt otherwise well-meaning people like Caputo. Now it’s shocking to see the effect that a little power has on the former prisoners, even when their role reversal is played for laughs.