Twenty years after a California jury declared O.J. Simpson not guilty of the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman after a trial that changed the way people watch TV, the two best things on American television this year have been FX’s The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and now ESPN’s O.J.: Made in America, a 7½-hour documentary that is the best piece of original programming the cable sports network has ever produced. The film is part of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series, which for the past seven years has produced some of the best sports documentaries around but has never previously come close to producing a work of this magnitude and power.

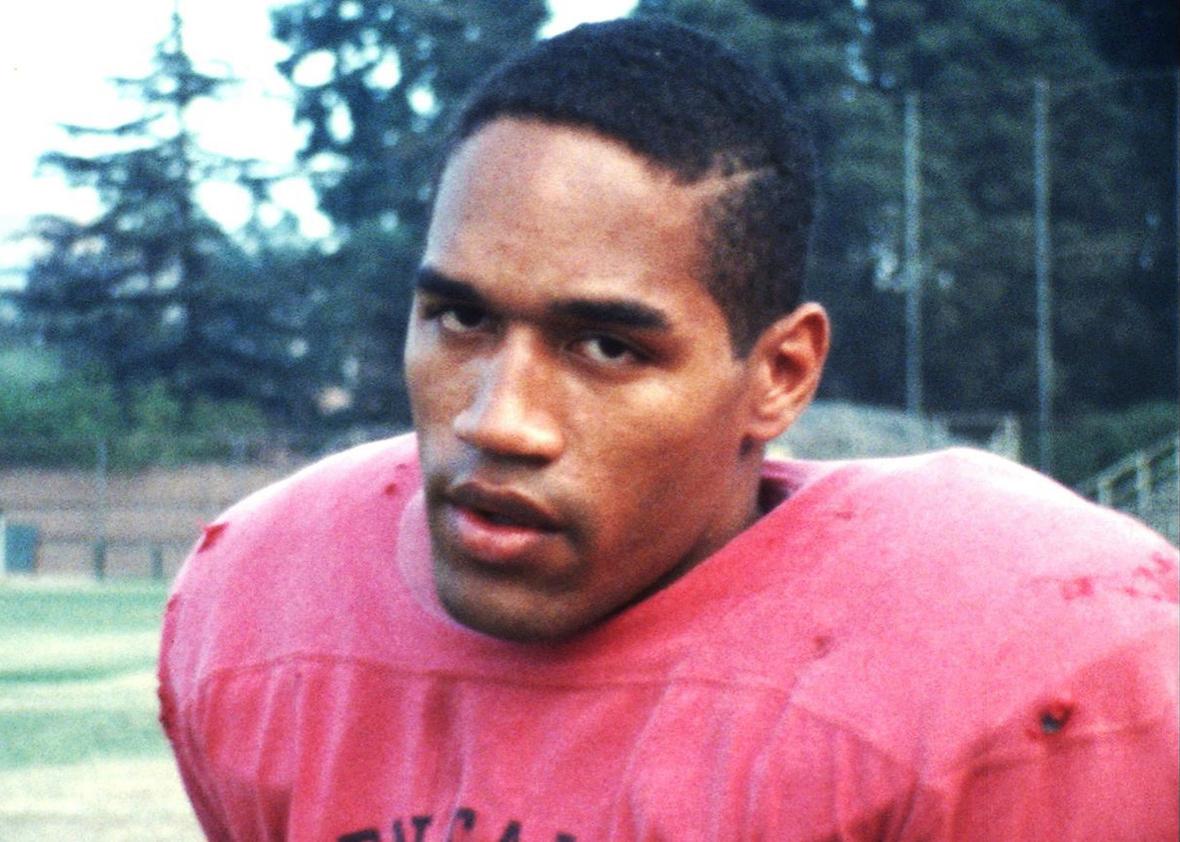

FX’s The People v. O.J. Simpson focused solely on the Simpson trial itself. The 10-episode miniseries wasn’t particularly interested in O.J. the man, his backstory, his alleged victims, or even really whether or not he committed the murder: It was, most basically, a legal drama, and a fantastic one. Made in America, on the other hand, is a different bag altogether. Ezra Edelman’s documentary gets at the entirety of Simpson’s story. While the murders and trial are certainly the centerpiece of the film, we start from the beginning, not the beginning of O.J. Simpson’s life (although we do arrive there eventually), but rather the beginning of O.J. Simpson’s life as O.J. Simpson. Much of the film’s first episode (the documentary will air over the course of a week) is devoted to Simpson’s football stardom at the University of Southern California, where he won a Heisman Trophy in 1968 and began building his reputation as one of the greatest running backs of all time.

Partly due to its virtuosic storytelling and partly to its sheer scope, Made in America often feels like several masterpieces unfolding at a single time. Simply as a documentary about law enforcement, the film is both painstaking and enraging. The first episode traces the racism and brutality that have marred the LAPD throughout the modern life of the city, up to the 1992 acquittal of the four officers who were caught on video assaulting motorist Rodney King, an event that sent the city into cataclysms just two years before Simpson was arrested for murder. Many of the least-sympathetic interview subjects in this film are cops, starting with Mark Fuhrman, the detective whose lies under oath about his own history of vicious racism did catastrophic damage to the prosecution’s case. Twenty years after the fact, Fuhrman seems vaguely repentant but also grossly self-pitying, unable to see the murders of Brown and Goldman and the attendant trial as anything more than something that happened to him. There’s a lot of tough talk from the other investigating officers as well, men who 22 years ago were so star-struck by Simpson that they disastrously botched his initial interrogation, even though his history of domestic abuse was well-known throughout the department.

As a film about race in America, Made in America is razor-sharp and remarkably nuanced. Back in 1996, the most incisive commentary on the O.J. verdict came from Chris Rock, who, during his now-classic standup special Bring the Pain, remarked simply: “Black people too happy, white people too mad.” Edelman’s film drives home the fact that many spectators who were so deeply invested in either a guilty or not-guilty verdict had reasons that far exceeded the specific crime at hand. This apparently extended to the members of the jury, one of whom callously blames Nicole for her own death on camera by saying that she should have left O.J. earlier, then admits that she’d voted to acquit as payback for the King verdict. Many of the conversations about “justice” that grew so heated during the Simpson trial had little to do with the actual defendant, let alone his alleged victims.

Edelman’s film also draws out one of the thorniest schisms at the heart of this trial, and of the public’s responses to it. On one side was a belief that O.J. was the tormented embodiment of race as an American cage itself, that no matter how famous and accomplished one becomes there is simply no escaping the injustices of being black in America; on the other side was a belief that race was a “card” being played by O.J. and his lawyers, that a man who throughout his celebrity had shown an abiding lack of interest toward the struggles of other black people was now cynically exploiting the sympathies and political energies of that community. It’s a testament to both Made in America’s remarkable sophistication and to America’s remarkably twisted racial pathologies that, by the end of the film, one has the sense that both sides may have been equally right.

But Made in America’s greatest triumph is as a film about fame—it’s the most provocative documentary on the subject that I’ve ever seen. One of the more fascinating aspects of Simpson’s post-football celebrity is how bizarrely amorphous it was. After his gridiron career ended in 1979 O.J. Simpson worked as a ubiquitous pitchman, but a bland one; as a sideline reporter, but not a very good one; as an actor, but an even worse one. After football, O.J. was just famous for being famous, which is the most insidious kind of fame there is, and yet an adult life spent accustomed to the adulation of millions who’d never known him clearly brought out monstrous tendencies. Simpson’s well-documented history of violence clearly stemmed in part from his own sense of entitlement, and that violence was in turn enabled by countless people who were blinded by his celebrity, many of whom happened to be members of the LAPD.

But Made in America is also a movie about fame as an addiction, a pathology in itself. The O.J. Simpson that emerges in this film is a man running, harder and faster than he ever ran on the football field, from the short period of his life before he became famous. Edelman’s film repeatedly emphasizes the degree to which Simpson strove to be “not black, not white, just O.J.,” and the lengths Simpson often went to distance himself from his own blackness and other black people. Early in the film, the sports writer Robert Lipsyte recalls O.J. once telling him how he felt proud when a rich white acquaintance casually referred to blacks as “niggers” in O.J.’s presence—to O.J.’s mind, this was proof that the acquaintance didn’t see O.J. as black. It’s quite possible O.J.’s addiction to fame sprung from his deep aversion to anything that reminded him of his childhood growing up in stark poverty in a San Francisco housing project, the one aspect of his life story that rendered him human.

In many ways I found the last episode of Made in America to be the most fascinating and wrenching 90 minutes devoted to everything that’s happened since those not-guilty verdicts were read. Simpson’s post-trial life has been one prolonged humiliation and degradation, a tawdry mess of scams and drugs and hangers-on and bungling attempts to some way, anyway, squeeze more profit out of simply being O.J. He’s spent the past eight years in prison for a botched robbery attempt in which he attempted to steal his own memorabilia at gunpoint and is eligible for parole next year. Who knows if he’ll get it, or if anyone will even care. F. Scott Fitzgerald famously observed that there are no second acts in American lives; O.J. Simpson must wake up every single morning wishing that were true.