The first rule of politics, at least as practiced by a certain kind of savvy campaigner: Give the people what they want. House of Cards, which returns like a hyena to the bloody carcass of Jed Bartlet’s America on Friday, was always a campy thriller running on a platform of highbrow seriousness. It polled best when it dispelled with the pretense that we dug it for its moral complexity, or even for the Shakespearian grandeur of its story arcs: Beltway aspirants launched to godlike heights and then dashed on the floor. Now, at the dawn of its fourth bid for office, House of Cards leans into the soapy twists with a fresh confidence gleaned, maybe, from the stranger-than-fiction success of Donald Trump. Extreme venality in our leaders doesn’t disturb us—it shocks and delights us. Terrific!

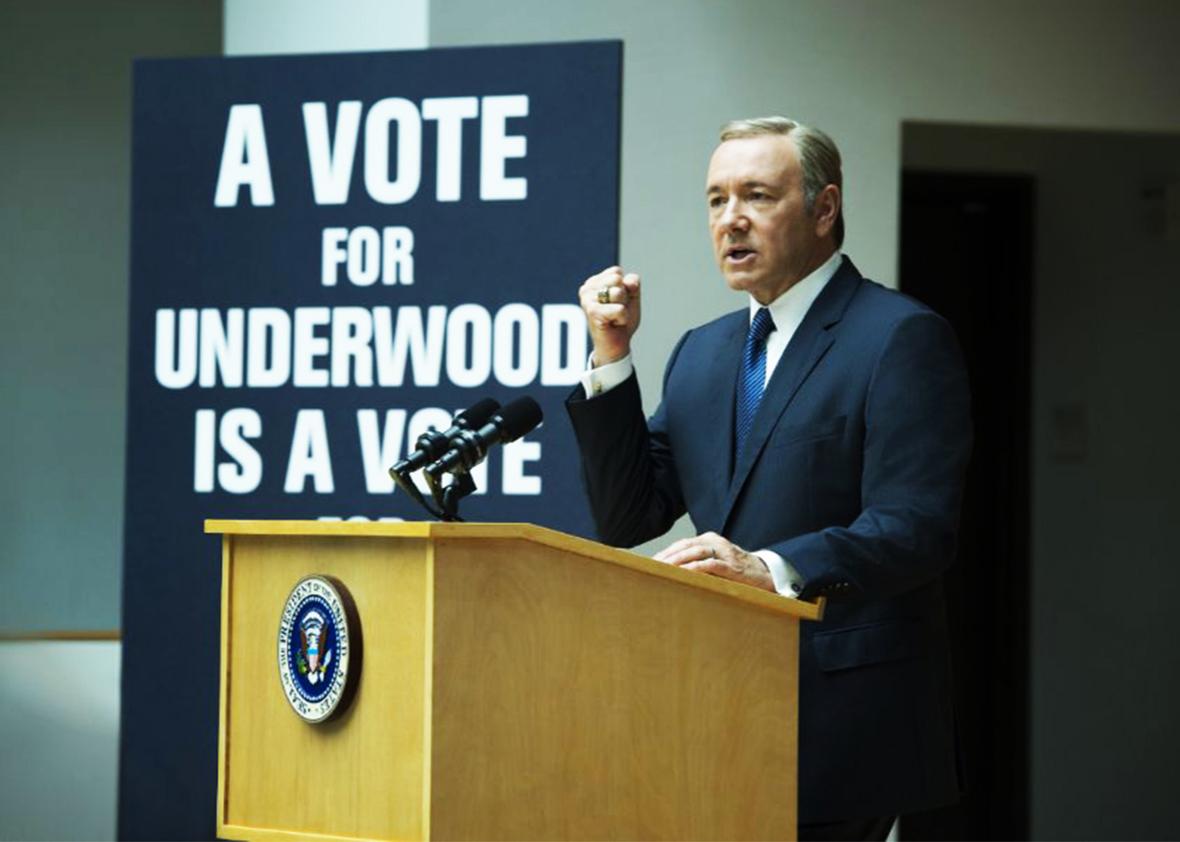

House of Cards has had to tweak its brand before, and these tight new chapters represent a course correction from Season 3, which Willa Paskin described as a “plodding relationship drama.” As the story resumes, Frank Underwood is resplendently code-switching between three modes: fuming rage, icy you-would-not-dream-of-defying-me assuredness, and folksy empathic charm. He’s all-in on his presidential race, where he faces tough opposition from principled DOJ alum Heather Dunbar (Elizabeth Marvel) and mild pushback from Jackie Sharp (Molly Parker), here more lackey than jackal, forced to contort to Underwood’s demands even as she despises him.

But Frank’s most dangerous challenger is, of course, Claire, who blew up the pair’s Macbeth-like alliance in the Season 3 finale and now thirsts to be not kingmaker but king. Claire spends her first few scenes of the new season drifting slowly down staircases or across darkened rooms, the camera caressing her austere, expressive face. Isn’t she fascinating? The show seems to ask. She is. Viewers know Frank, though we can rarely anticipate the ingenious, dastardly machinations through which his soulnessness will manifest. Claire presents a mystery not only to us, but to herself. With her husband out of the picture (literally: they don’t share a frame until late in the premiere), who is she? What does she want?

It doesn’t take long for the more enigmatic Underwood’s dreamy holding pattern to shatter, and for the choreography to start. Claire wants, first off, a congressional district, and getting it will require cooperation from a network of iron-willed, variously motivated women. Scream’s Neve Campbell is great as Leann Harvey, a steely, paycheck-minded “fixer” who keeps a gun in her desk drawer. Cicely Tyson plays a Texas congresswoman resentful of Claire’s “carpetbagging” encroachments onto her largely black turf. (A storyline involving a leaked photo of Frank’s father hobnobbing with a Ku Klux Klansman quaintly envisions white supremacy as political kryptonite. If only.) Ellen Burstyn witches it up as Claire’s mother, one part twisted Southern Gothic—“that’s just Mother killing a lizard,” Claire informs a guest, as an ominous pounding comes from the other room—and one part brittle socialite: Her assessments of Frank include “He is a classless graceless shameless barbarian” and “I hope he dies.”

The old gang is back, too, because a plot creased this liberally with reversals, upsets, and unlikely alliances needs plenty of history. (Around the fourth episode, a huge twist brilliantly reconfigures the chessboard, some characters swirling to fill a leadership void while others shadowbox the past.) Lars Mikkelsen reprises his Putin-esque act as a lecherous Russian statesman and wildcard; Meechum and Catherine and a few surprise cameos from prior seasons keep things cooking. The specimen known in Season 3 as Sad Stamper has embraced the dark side, fulfilling his destiny as a silky-voiced menace prone to bursts of unpredictable violence. Taking his baton of despond: Sad Lucas, who leaves prison as a protected witness only to find himself cleaning rental cars, fending off sexual propositions from co-workers, and ghosting through a desolate, Internet-less apartment in Ohio—the House of Cards version of a puppy walking down a street lined with broken glass.

The new episodes—sordid little dopamine bursts, each as gratifying and wrong as a dirty campaign contribution—feature some delicious writing, parceled out in typically sharp one-liners and asides. (House of Cards dialogue has always reminded me of a Kurt Vonnegut novel, crammed with snappy aphorisms like “the president is the people who work for him.”) The lines that stick, though, aren’t quips but moments of honesty: Amid all the lies, a character’s decision to speak the truth can feel revelatory, as can the outlandish context in which a universal human experience surfaces. (It seems like a TV drama cliché for a traumatized character to stare numbly into space and say: “I feel nothing.” Yet when these words are spoken in House of Cards after a major plot event, they’re stunning.)

“Your fingerprints are all over this money,” one political strategist snaps at another. The second fires back that she thinks his fingerprints are all over a congresswoman. A little later, a character has his handprint drawn onto the wall of the White House, where it replaces a painting of a Confederate flag struck by lightning. None of this symbolism is remotely subtle, and yet it captures the extent to which, in House of Cards, the personal—the human, the intimate, the bodily—seeps into the political. And politics, in turn, can’t help corrupting concepts like family, partnership, mate, especially for the Underwoods.

In that spirit (and without giving too much away), Season 4 seems to be dialing up the psychological darkness as the walls separating different compartments in its characters’ lives collapse. While Frank occasionally addresses viewers directly, his Richard III–style chats are increasingly phased out in favor of a new surrealist tic: hallucinations. The people he’s murdered or betrayed come back to haunt him, not unlike in the original Scottish play. House of Cards has been criticized for not giving Frank a formidable enough adversary. What if his greatest enemy is himself?