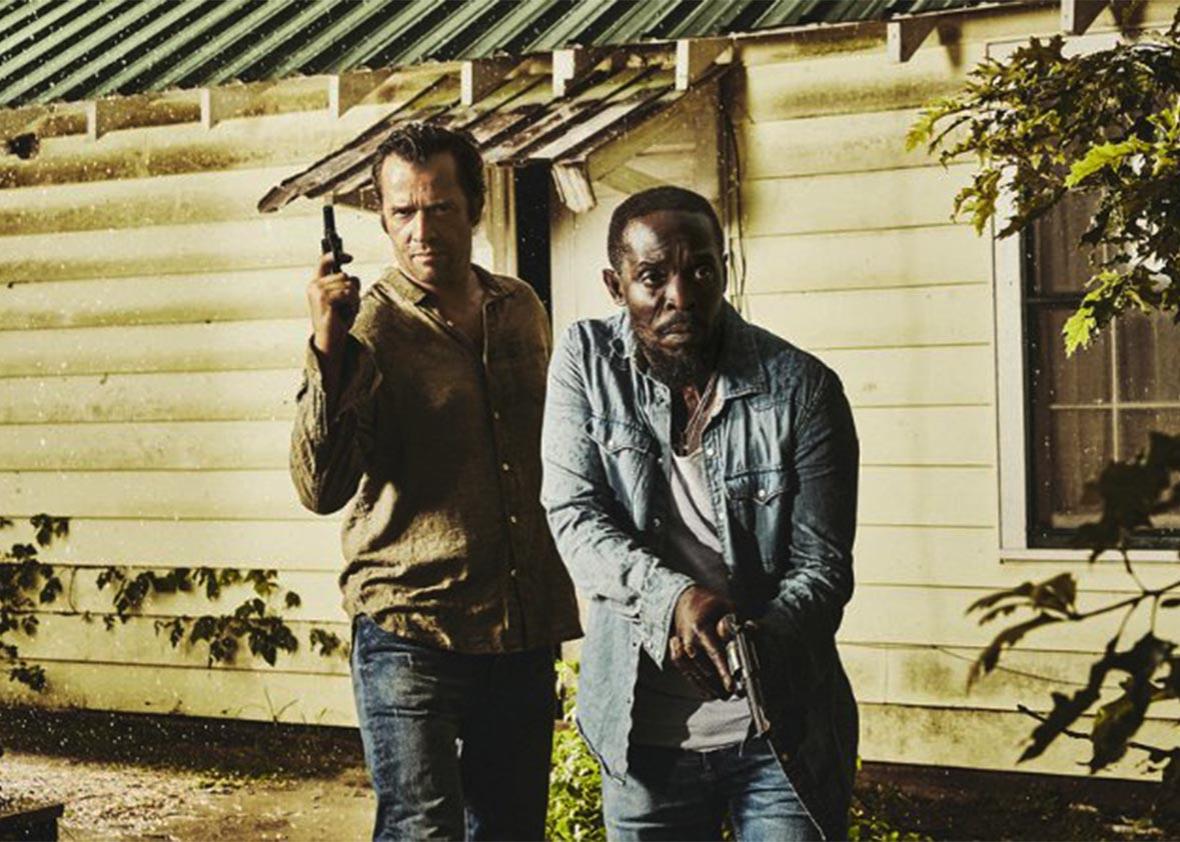

As a TV critic, my bias toward my medium is such that I rarely think, that would be better as a movie. But this would be better as a movie was all I could think while watching the first three episodes of Sundance’s Hap and Leonard, a shaggy-dog caper set in East Texas in the late ’80s. The show is a dusty, sunlit noir about devoted best friends Hap (James Purfoy) and Leonard (Michael K. Williams) who, in lackadaisical Elmore Leonard style, get caught up in a zany scheme involving a missing million dollars, Hap’s ex-wife and maybe femme fatale Trudie (Christina Hendricks), her current husband and his oddball crew of former radicals hoping to keep the idealistic spirit of the ’60s alive by corporatizing, and a pair of spandex-wearing sociopaths. This description sounds chock full enough to demand a TV series, but plays out as only chock-full enough to demand two hours.

Hap and Leonard are an odd couple: Hap’s white, straight, laid-back, and went to jail in the ’60s rather than go to Vietnam. Leonard’s black, gay, particular, and served in the Marines. They are inseparable, and the show opens on the pair working in the rose fields of East Texas in matching threadbare cowboy hats, the least thorny setting in which they will find themselves. The two are a platonic unit, gruffly and lovingly insulting one another, a package deal, close enough that Hap can freely use the N-word with Leonard. Then Trudie waltzes back into Hap’s life and bed, much to Leonard’s consternation, and makes him a proposition he can’t refuse.

Hap and Leonard is full of memorable characters that it introduces with panache then idles with, reiterating what we already know, a #longform piece that would be better if it were not so long. (Brevity! Remember when it was the soul of wit?) Leonard calls Hap on the phone after Trudie’s visit, like a concerned, scolding parent, and this does a better job establishing the unique tenor of their relationship than the many moments that come: This is the moment that belongs in the movie. The long play of television is supposed to give writers, and audiences, time to get to know characters more intimately, but Hap and Leonard repeats itself, pleasantly enough, instead of going deeper. In addition to Hap and Leonard, there’s a bomb-blasted former leader of a Weather Underground–type group, an obese oddball who has spent time in analysis, and a wannabe guru hoping to invest ill-gotten money in a world-bettering operation, all played for deadpan. They each have a great moment or two, and then countless, needless more.

Some people will surely enjoy the meandering nature of Hap and Leonard and its drawling vibe, punctuated by moments of violence and alligators. The show also—like The Americans, Halt and Catch Fire, and the canceled The Carrie Diaries—sends viewers back to ’80s, but gently: Only the on-point soundtrack and constant references to Vietnam telegraph it’s a period piece, not the wardrobe or lack of cellphones. Those Vietnam references also tie the show to Fargo, the second season of which was set in the ’70s, and featured a veteran, played by Patrick Wilson, returned from the horrors of war to the unexpected horrors of the Midwest. In Hap and Leonard’s early episodes, however, the characters are finding it more difficult to get out from under the late ’60s’ idealism, rather than its violence—though they can’t quite escape that either. Once they lived lives full of meaning. Now it’s the ’80s. But really it’s 2016, and so their struggles, their heist, and their smushy Southern accents are sprawling on a small screen that’s gotten too big for its own good.