Packaging matters. Despite warnings to the contrary, we judge books by their covers, products by their wrapping, and TV shows by their networks. Vinyl, a new drama about the 1970s music business, comes in a very shiny suit indeed. It was created for HBO by Martin Scorsese, who directed the first episode; Mick Jagger; Rich Cohen; and showrunner Terence Winter, a writer for The Sopranos and the creator of HBO’s bootlegger period piece, Boardwalk Empire. The boldface names don’t end there. The show uses real people, played by actors, to bulwark its fictional world. Andy Warhol, Roger Daltrey, Johnny Thunders, and Alice Cooper make appearances, and the soundtrack comes to life with performances from the likes of Janis Joplin, Little Richard, and Howlin’ Wolf.* How could you go wrong with such a guest list? But Vinyl is made in the spirit of a great party, rather than a great TV show. It looks fantastic, and it’s lively and rambunctious, with good music, an endless supply of drugs, and enough ill-considered drama to give everyone something to gossip about the morning after.

Despite enjoying the loftiest reputation in all of TV-dom, HBO is hard up for a new drama. Game of Thrones is winding down as is the excellent and little-watched The Leftovers, while there may or may not be a third season of True Detective. The long-gestating sci-fi Western Westworld has been delayed; a miniseries about Lewis and Clark got scrapped even though several episodes had been filmed; two projects with David Fincher came to naught; and HBO’s head of drama development just left.

Looking to steady itself, HBO has once again grabbed onto reliable partners like Scorsese, Winters, and David Simon, whose show set in the 1970s porn industry starring James Franco, The Deuce, just got picked up to series. Scorsese is an impressive talent to be associated with, but he also directed the first episode of Winter’s Boardwalk, evidence that Marty’s involvement in a TV show does not a masterpiece make. Boardwalk lasted for five seasons, but it never did more than yeoman’s work. As the prestige drama meant to replace The Sopranos—because HBO had passed on Mad Men, the drama from a Sopranos writer that actually replaced The Sopranos— it only ever filled its time slot.

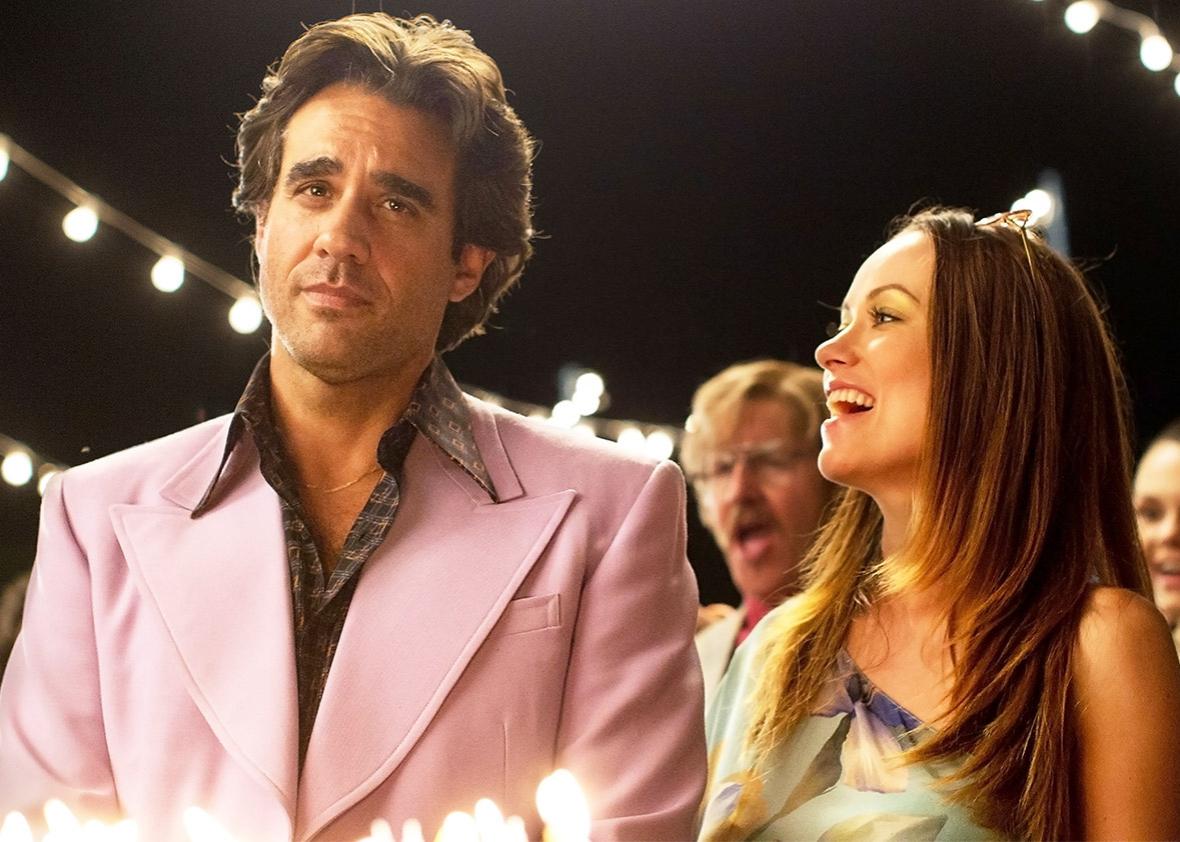

Enter Vinyl, which also airs on Sunday nights. It stars Bobby Cannavale as Richie Finestra, a prototypical Scorsese hero: an ethnic Italian who grew up on the mean streets of New York City and who built up his record company, American Century, with the help of a little mafia-laced cash. Richie has a golden ear, but he’s lost touch with rock ’n’ roll. His company is tanking, full of toothless artists like Donnie Osmond, and Richie and his co-owners are trying to sell it to a bunch of clueless Germans for a fortune. Richie has been clean for years, living with his wife Devon (Olivia Wilde), a former member of Warhol’s Factory, and their kids up in Greenwich, Connecticut, but over the course of the first episode he falls off the wagon. We meet him holed up in a car buying drugs in the abandoned streets of SoHo, soon to wander into a raucous New York Dolls show at the Mercer Arts Center, where, high out of his mind, he has a musical revelation.

Vinyl has two stylistic lodestars: 1970s New York, with all its febrile, fertile grit, and the Scorsese oeuvre, in which cocaine-fueled maniacs have too good a time before their fall. It painstakingly attends to both of these influences, making itself into a high-quality Forrest Gump in which major moments from both ’70s rock ’n’ roll and derelict New York—graffiti covered subways! Porn-ridden Times Square!—and old Scorsese movies are recreated with flair, panache, and, whenever possible, very loud breathing. Not so dissimilarly from Boardwalk Empire, it has prestige everything—sets, talent, camera work, visuals—but an ersatz essence.

The Scorsese hallmarks are thick as the rails Richie snorts off anything he can find: his hand, a table, a rearview mirror. Richie begins the show with a voiceover that could be straight out of Goodfellas, if Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill had been in the record business, or The Wolf of Wall Street, if Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jordan Belfort had an ethnicity. “When I started in this biz,” Richie begins, “rock ’n’ roll used to be defined as this: two Jews and guinea recording four shvartzes on a track.” As both the dictates of prestige dramas and Scorsese require, murder is needlessly added to the typical cocktail of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. Even that which is not strictly Scorsese is Scorsese adjacent: Throughout, Cannavale does a winning impersonation of Al Pacino atop a mountain of Bolivian marching powder; after blowing lines, one time he even says, “Hoo-ha!”

Vinyl and Mad Men both take place on the commercial side of a creative industry riding the sea change of the ’60s revolution. But they have very different spirits: Mad Men is all control, Vinyl is all cocaine. Mad Men allowed its characters to be outright racist and sexist, knowing it would play as such to its audience. It made the ’60s look sleek and elegant, a debonair style that covered up the unchecked desires of the white men in charge of Sterling Cooper. Vinyl makes the ’70s look debauched, free-wheeling and unhinged, but it protects its hero from outright bigotry.

Back in the ’50s, Richie became the manager of a great blues singer named Lester Grimes (Ato Essandoh). When Richie started to work for a label, he got Lester to record as Little Jimmy Little, turning out more upbeat race records than the blues Lester preferred. When Richie finally struck out on his own, he was unable to buy Lester’s contract, leaving Lester to languish away as Little Jimmy, under the thumb of a mob boss who didn’t get his music. Essandoh, unlike everyone else in the cast, is allowed to be quiet at times, and so has more gravitas. His storyline has some heart. And yet this version of a white record executive capitalizing on black talent is a vast soft-pedaling of the kind of gross racial manipulations at the heart of the record business. Richie doesn’t disrespect Lester’s sound, he doesn’t make a fortune off it, he doesn’t steal it and deliver it to a white outfit so they can make a fortune off of it instead.

Richie may be a charming and out-of-control cokehead who gets in fights in the office and says nonsense like, “My skills have transcended to the spiritual level,” but he’s relatively open to seeing talent where it is, even if that talent is female. Juno Temple plays Jamie Vine, the Peggy Olsen of Vinyl, a young, ambitious woman who begins the show as a secretary, which in Jamie’s case means she provides coffee and drugs. Jamie wants to be an A&R rep, and while everyone else at American Century is signing safe and silly bands, she brings in a proto-punk outfit called the Nasty Bits. (The Nasty Bits are headlined by Kip Stevens, played by James Jagger, Mick’s son. He is good enough in the part for this casting to go in nepotism’s “win” column.) Jamie has drive and an ear, but none of the slovenly men at American Century can see it, except for Richie, who like Don Draper with Peggy Olsen, is just barely willing to consider her.

There is also the matter of Devon, Richie’s wife. Through the first half of the show, Devon is stuck in Greenwich, having given up her happening life to make a home, furious at Richie for falling back into cocaine. Like all the other parts in Vinyl, there’s lots of screaming and emoting and crying, but that’s just a filigree laid over what is fundamentally the hectoring wife role. There is also a little problem of chemistry. Cannavale and Wilde have no heat between them: The first time they screw, they have a secret assignation in a bathroom, where Richie grabs Devon by the throat and they have sex against a sink, which sounds hot and urgent and a little menacing, but only in the typing of it.

In future episodes, Vinyl introduces Andrea Zito (Annie Parisse), a fierce PR woman for a rival record label who has a history with Richie. There’s a good reason the two didn’t work out: Richie found her too familiar, too Italian. Richie wanted his shiksa goddess, proof, as it was for Philip Roth and Woody Allen before him, that he’d made it into the white, and not ethnic-white, mainstream. But when Parisse appears, chewing up the scenery as ferociously as Cannavale, the show perks up: Two Italian-Americans giving as good as they get is great rock show compared to the uptight performance art that is the marriage of a WASP and Sicilian, drawn together by their mutual attraction to the other’s relative exoticism.

Richie is a kind of musical Zelig; there is no sound lost on him. He gets the blues, he understood the Velvet Underground and Led Zeppelin, he’s hip to the power of punk, he hears the hits in ABBA, and he is even alive to nascent hip-hop. There is something phony about the flawlessness of Richie’s miracle ear and its proclivity for legends. He doesn’t just have taste; thanks to the show’s writers, he has the benefits of hindsight. Cannavale seems totally out of place in the modish black suits he wears to see the Velvet Underground, and his insta-grooving to turntable stylings of a man who turns out to be Kool Herc is too prescient to be true. And for all his catholic taste, when he yells passionately, in tired terms about what music can do— you know, make us feel alive, make us want to fight, to screw—he is talking about a very specific kind of raucous rock, while ignoring what Vinyl ignores overall: the other more interior, plaintive emotions that good music can makes us feel, too.

*Correction, Feb. 10, 2016: This article originally misspelled Johnny Thunders’ last name.