In the first episode of Hannibal’s third season, the title character serves one of the most elaborate—and entrancing—dishes that has ever been presented on television. It’s the roasted leg of a long suffering animal, richly glazed and studded with spears of sugar cane. Inspired by a Northern Chinese dish of candied pork belly, this is the kind of image that’s designed to make a certain class of viewers salivate. And that, of course, is what makes it so terrifying.

Those familiar with Hannibal’s title character—and who isn’t?—should know at once that what we’re looking at here is supposed to be human flesh. And yet it appeals, entrances even, all the same. This is a testament to the efforts of Janice Poon, the show’s brainy food stylist, whose work, as she puts it, has to tiptoe through “that liminal space between being seduced and being repulsed.” But it also speaks to the baroque aesthetics of the series as a whole, aesthetics that are, as showrunner Bryan Fuller tells me, fundamentally culinary. Hannibal’s world is Hannibal’s world, one in which everything is potentially edible.

Bloody as Hannibal is, it’s this fascination with food that contributes most to its climate of horror. At times, the dishes themselves are frightening. On her blog, Feeding Hannibal, Poon suggestively refers to the sugar cane leg as her “Pinhead the Cenobite” roast, alluding to the monstrous recurring villain of Clive Barker’s Hellraiser series. More unsettlingly, she consciously incorporates sliced lotus roots, peeled pomegranates, and other trypophobia triggers onto plates. Such foods are inherently unsettling, leaving us with the feeling that, as she puts it, “something alien has been implanted while we were sleeping.”

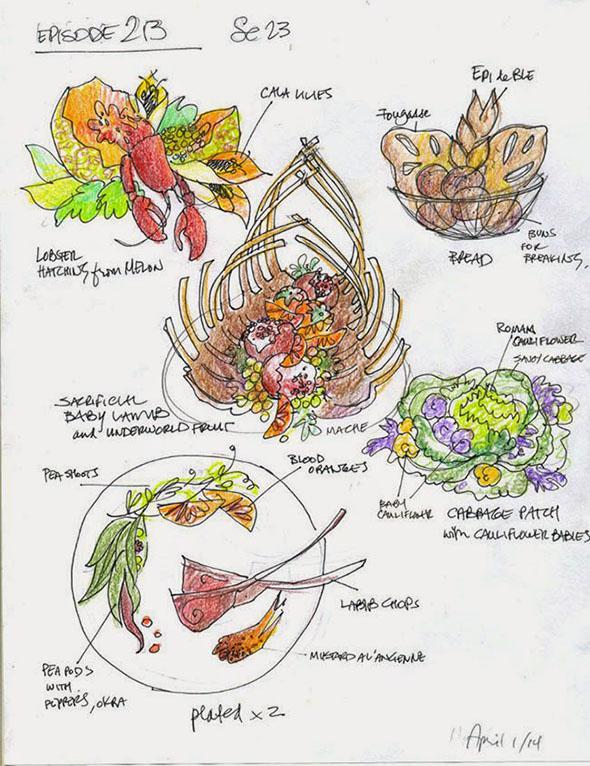

Image courtesy Janice Poon

Though it is sometimes disquieting, Hannibal’s food always looks delicious, and that appeal is inextricable from the charms of the show as a whole. Fuller explains, “The food [Hannibal’s] preparing has to look delicious and enticing, and has to confuse the audience about what they’re looking at.” Poon seconds this point, telling me, “It has to be appetizing. It has to be something that your hand is reaching out to take, even as you say, ‘No, no, hand. That could be people!’ ”

This play of the familiar and the unfamiliar, of the tasty and the distasteful, is also central to the way the series references its source material—both Thomas Harris’ novels and the films based on them. Fuller and his collaborators clearly expect that viewers will be familiar with these earlier works, but they use that familiarity to throw their audience off guard. Famous images from the films, for example, recur here and there, but they appear in radically new contexts, leaving the viewer with the uncanny sense that strangers hide behind the faces of old friends.

Photo courtesy NBC

Where Fuller’s Hannibal transforms our ideas about its antecedents, it almost always makes them more beautiful in the process, as well it should. Few meals sound less appealing to me than the one for which Hannibal Lecter is most famous: “liver with some fava beans and a nice chianti.” If I’m being honest, it’s not the source of the meat that troubles me as much as the total plate, as flat on the palate as it is dull to the eye. And that wine pairing: How pedestrian! Call me a snob if you want, but I blame the more recent incarnation of Hannibal, one whose aesthetic sense has led me to expect a better class of cuisine from my cannibals.

Fittingly, just as Hannibal manipulates our knowledge of Harris’ larger mythos, so too does it play with our expectations about food television. Indeed, it draws on that genre’s conventions almost as frequently as it does those of horror cinema. Patti Podesta, one of the show’s production designers, acknowledges in The Art and Making of Hannibal that the protagonist’s kitchen “resembles a cooking show set.” And Nick Antosca, a current writer and producer on the show, makes the connection between Hannibal and celebrity chef culture still more explicit, telling me, “We admire great chefs, and this version of Hannibal Lecter is the greatest chef in the world.”

To help confirm that impression, the producers rely on star chef José Andrés, who explains that his role is primarily technical. “My input is mainly about how Hannibal would cook a certain body part,” he writes, “and I have to think of something that would look appetizing once it’s cooked.” Producing that visual impact still falls to Poon, and Andrés happily acknowledges that the results are frequently impressive: “[T]here are times when my mouth is actually salivating when I’m watching the show,” he admits, “and that’s what we’re trying to achieve with the audience.”

In this regard, the work that Poon and Andrés do on Hannibal may not be entirely distinct from their contributions to more conventional food television. No cliché is more central to the programs and personalities that Podesta and Antosca reference than the phrase, “You eat with your eyes.” Above all else, its familiarity speaks to the triumph of food television, a genre hampered by the absence of the aromas, textures, and tastes that make a meal meaningful. The Food Network and its ilk have trained us to look, teaching us to delight in images of elegantly composed plates as much as we might an actual dish.

Photo courtesy Loretta Ramos

Exploiting this televisual fantasy, Fuller’s series uses Hannibal’s sumptuous compositions to make its viewers complicit in his most monstrous crimes. “If they find what’s on the plate in front of them appealing, they’re sitting in Hannibal’s seat,” Fuller explains. Most of the people Hannibal feeds on the show have no idea what they’re eating—they are little more than the victims of a cruel joke. Viewers, however, are in a privileged position, compelled to participate in the show’s cannibalism precisely because they’re caught up in its illusion of culinary refinement. Like Eddie Izzard’s Dr. Abel Gideon—who has his sugar-cane-studded leg served to him—we dine with Hannibal when we watch, at once perpetrators and victims.

This irresistible complicity is apt in part because Hannibal’s search for connection is one of the show’s most consistent themes. Narratively, Hannibal constantly circles around the search for family, and on this show, true family are those who share our pleasures. Fuller’s Hannibal is man in need of both audience and orchestra, an ensemble that will appreciate the sinister music he composes even as they play it with him. When he enjoins others to enjoy his food—to revel in his way of living before they understand its cost—he isn’t taunting them so much as he’s inviting them to join him.

Photo courtesy Janice Poon/Feeding Hannibal

Virtually everyone who loves this criminally under-watched series has found themselves in its protagonist’s shoes. We have to slyly convince others to try out things they’re sure they’ll find unpleasant. I know I’ve been there: My girlfriend gave up on it after the second episode, in which a pharmacist buries diabetics alive and grows mushrooms from their sweetened flesh. (This, she said, was too personal. I am a diabetic and she couldn’t stand the thought of it happening to me.) I keep trying to lure her back, to convince her that the rest of the series is comparatively harmless, partly because if I’m going to feel guilty, I don’t want to feel that way alone.

And yet I’m not alone, not really. Fuller, who describes himself as a pescetarian, suggests that all of us have a little bit of Hannibal in us, all of us who eat meat, anyway. “It [strikes] me as very comedic that people get so bent out of shape about cannibalism when they’re meat-eaters,” he says. Though she is a happy carnivore, Poon concurs in her own way, observing, “Just clawing our way to the top of the food chain has been an ugly, ugly matter. Perhaps that’s why we have to decorate [our meals] with all the mannered ceremony and the elegant cutlery.” In this sense, whenever we embrace a refined aesthetic, we’re covering over our basic savagery. And no one is more refined than Fuller’s Hannibal, whose charms are the photonegative of his crimes.

Images courtesy Janice Poon/Feeding Hannibal

What charms they are! Poon plates as she paints, “color blocking,” in her phrase, constellations of meat that draw the eye through cinematographer James Hawkinson’s otherwise pervasive shadows. Even if you wouldn’t want to eat the things she shows you, even if you think you know better, they call you closer. And Hawkinson’s camera is right there with you, “creeping along at table level,” as Poon puts it. It all but snuffles as it approaches, reminding you that you are, at core, an animal—an animal most of all when you are eating other animals.

Many have claimed that the problem with the Hannibal franchise is the way it turns its monstrous protagonist into a hero. Though it acknowledges his seductions, Fuller’s Hannibal returns its title character to the muck, putting the awful back into offal. And by inviting us to taste the things he makes of it, it drags us down with him.