On Thursday night’s episode of Louie, the series’ long-running tension between cosmetic and substantial character development gets literal: Louie (who in the Season 4 episode “Model” accidentally punched a woman) gets beaten up by another woman who is small, blond, and pretty. Plagued both by stereotypical male anxieties (how do you tell people you got “beaten up by a woman”?) and stereotypical female ones (how do you hide your bruises?), Louie goes to Pamela for help. The experiment in role reversal culminates in Pamela giving him a makeover—and not just a makeover that hides the bruises. A full makeover: Pamela makes Louie over in her own image, complete with black eyeliner. And he really, really likes himself this way, marveling at his feminized reflection in the mirror. It might be the logical conclusion to Louis C.K.’s comic philosophy of empathy: Louie finally becomes the thing he loves.

It’s hard to imagine an episode that more clearly demonstrates just how far Louie’s relationship to love has traveled over the course of his show. If he starts off loving women in black eyeliner—Liz, Pamela—he ends up with his eyes blackened by women, literally as well as cosmetically. And the symbolism of makeup has evolved, too: from being literally cosmetic, a superficial means of “covering up” to revelatory, a vehicle for radical imaginative transformation.

Louis C.K.’s stand-up has long been dedicated in large part to the ugly self-loathing that sometimes attends masculine desire, and the ways women are subjected to it. “A woman saying yes to a date to a man is literally insane and ill-advised,” C.K. says in his stand-up. “Imagine you could only date a half-bear, half-lion.” “I’ll get into your car with you with my little shoulders,” he says, ventriloquizing a woman. “ ‘Hi, where are we going?’ ‘To your death, statistically.’ ” He talks about how women use kindness as a weapon—hugging a man they don’t want to kiss. “Men think this is affection but what this is is a boxing maneuver. Don’t kiss me, you piece of shit!”

Season 4 even shows Louie experimenting with trying on the perspective of a woman navigating the world. One of the best scenes of the season has a man talking to a woman on the subway so avidly that Louie at first thinks they know each other:

Screenshots via FX

When she gets off, leaving the man gibbering to himself, Louie realizes she was being both kind and accosted. Feeling sorry for the man, he takes her place.

But it’s not the same thing—the man has to look up at Louie, and Louie’s physicality isn’t cowed the way the woman’s was. When it’s one white man looking at another white man, Louie seems to be suggesting, no one has anything to be afraid of.

Louie’s perspective on empathy and gender relations is one that could very easily lend itself to paralysis. After all, the most obvious logical solution for a Straight White Man who wants to be conscientious and careful not to exploit his power and privilege in the world is to opt out. To withdraw. Early seasons of Louie show his character doing just that. He’s tentative and apologetic with women and deals with desire by becoming a compulsive masturbator. It is, of course, a dumb solution, as unfulfilling as it is inhumane. And it doesn’t last: in Season 3’s Late Night arc, Louie’s ex-wife, Janet—with help from David Lynch—persuades Louie that refusing to engage isn’t a solution to the problem of “privilege”; it’s a copout. You don’t get to say you don’t do jokes. You don’t get to masturbate in the dark forever and remain a good father. You seek fulfillment. You do a joke. You date. You try.

So these five seasons have shown Louie transition from that state of near-paralysis, where he’s so passive he can’t even tell his date (played by Chelsea Peretti) that her neighbor flashed him—to the opposite extreme: an active, overblown drive that leads him to behave in ways that come close to rape. Season 4 is a brilliant exploration of his hypercorrection in the opposite direction. Instead of subordinating every aspect of his life to fatherhood, he goes for the things he wants in ways that impinge on the people he ostensibly loves. Amia, Louie’s Hungarian girlfriend from Season 4, was angry that they spent the night together. Pamela freaked out when he wouldn’t let her leave. “This would be rape if you weren’t so stupid,” she says.

But so far, Season 5 seems to be the story of Louie pulling back, in his relationships with women and other people, into something less manic and grabby—something closer to equality. He’s still repeating old patterns—Louie is nothing if not a brilliant theme and variations—but these are productive (as opposed to rote) re-enactments.

This episode isn’t about Louie becoming a woman; this isn’t a matter of identity. But it is about Louie figuring out forms of love that overwrite love as possession—or love as winning—in favor of things like empathy and comprehension. Louis C.K.’s stand-up on what it must be like to be a woman has gradually given way to experiments wherein he lets go of his masculinity and actually tries some woman-stuff out. In Season 3 he’s sewing because he has to—the Christmas finale has him desperately trying to fix an eyeless doll and sewing her back together. By Season 5, he’s knitting for pleasure. In Season 4, he repeatedly allows himself to be helped by old ladies. He buys a vibrator and uses it for his back. If in earlier seasons he cooks grouchily for the girls, by Season 5 he’s shopping for expensive cookware and volunteering to make fried chicken—which he makes expertly and enjoys making, even if it doesn’t quite work out.

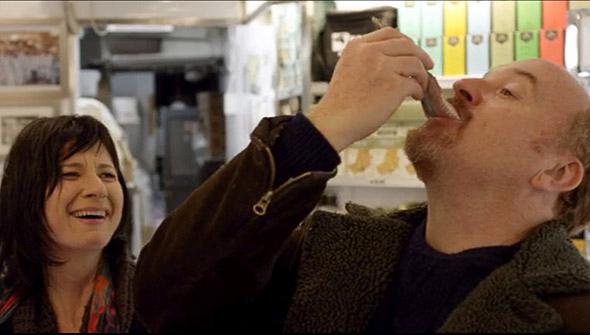

Season 4 was about Louie doing it “wrong” when it comes to putting himself in the place of the women in his life. Take these two stills, one from Season 3, where he first meets Liz and tries the herring, the other from season 4:

Screenshot via FX

By the time we get to Amia, Louie’s putting the fish in his own mouth:

Screenshot via FX

The difference between these superficially similar shots is huge. The second echoes the first but hints at the ways in which Louie’s going too far: Amia hates the herring. (She eventually spits it out.) Louie’s attempt to become Liz here didn’t quite work. Granted, he’s just doing what so many of us do, reliving an earlier happy moment with someone new, but he’s doing so in ways that don’t quite see the woman he’s with. (“Most people really like it,” he says apologetically to Amia afterwards, admitting he was working from a generalization.) Liz is looking at Louie as she feeds him in the shot above. Louie’s just looking at the fish. Poor Amia is herself a kind of (red) herring—she’s a projection and she’s not at the center of the frame; there’s an empty space where Liz’s face should be. Despite Amia’s sweetness, this is a sad and empty re-enactment. Louie’s sometime desire for Liz and his newly discovered agency blinds him. He missteps, oversteps. Season 3 is rife with examples of Louie misunderstanding how to go after what he wants, supplying the words Amia’s English can’t produce, and accidentally assaulting women in hallways because he’s convinced they want it.

It’s telling, then, that the next time we see Louie in a hallway with a woman—in Season 5—the repetition registers an even bigger change. Louie, it seems, experienced a kind of baptism in that tub with Pamela in the Season 4 finale. When he has sex with the pregnant woman in the hallway of her apartment, the scene is the opposite of its antecedents despite seeming similar. She stops him from leaving, she pressures him into sex—she’s playing Hallway Louie from last season, and Louie’s playing Hallway Amia, Hallway Pamela.

Liz marked the beginning of Louie’s ability to inhabit both positions in the hallway, so to speak. Liz was the one who first made Louie try on lady’s clothes: a gold lamé dress. And Liz’s death coincides with the true beginning of Louie’s long experiment with self-actualization—a new start that was violently and cinematically expressed in that Season 3 finale, when Louie spent New Year’s Eve in Liz’s hospital ward and then set out in aggressive pursuit of some form of happiness.

Recall the surrealist agonies he suffered in that same episode, trying to fix his daughter’s doll, whose eyes had fallen into her head. We’ve had hints of gender fluidity on the show before—like when Louie kisses the sheriff who rescues him in the South—and we have it again in Season 5 when he tenderly kisses a male mannequin. But his first encounter with the doll is a deep exploration. Louie starts by taking her hair off, hacking her head open, and shining a light inside.

By the end of the sequence, the doll—bald, bearded with orange paint in a botched touch-up attempt—has become a kind of figure for Louie himself. It’s his first experiment with makeup, and, like any major reinvention of the self, it’s extraordinarily painful.

The doll bit is hilarious, but it also demonstrates that Louie’s approach to everything (the show, comedy, gender) is actually the opposite of the slapdash indifference that some of his antics may suggest. It shows massive, exhausting, life-sapping effort. The kind of effort Louie would never have shown toward anything at the beginning of the series. There are moments of frustration and violence during his exploits with the doll—at one point he even weeps—but one thing is clear: He is trying. Specifically, he is trying when it comes to understanding how women work. The doll sequence shows the extreme frustration and care with which he’s trying to rescue his girls from a reality where dolls have no eyes. It also shows Louie’s ongoing process of self-improvement over the course of the series. If Season 4 is largely the story of Louie, having learned to try for what he wants in Season 3, overstepping into near-coercion, Season 5 is about stepping back and, rather than taking what he wants, becoming it.

The tragedy of this arc is that Louie and the woman he loves are not on the same journey at the same time. Pamela’s been growing toward Louie too—by Season 5, she’s wearing a pair of glasses remarkably similar to the ones she mocked Louie for wearing in Season 4—but she’s not where Louie is, emotionally or otherwise. They’re closer than they’ve ever been: By the end of their role swapping they’re exhausted, in bed, both wearing her trademark black eyeliner and his trademark black shirts. But it’s not close enough. For Louie, that encounter broke into a new form of intimacy. It was an escalation. For her, his insistence on meaning makes the relationship impossible. She wants their relationship to remain open—in what we’re perhaps supposed to understand as a stereotypically male articulation of the ideal relationship. Louie—who even says “I’m not sure why I’m on this side of the argument”—wants it to be a closed loop.

If Season 4 ended with Louie lecturing Pamela on what she wants when he has her cornered in the hallway—and telling her he’s going to do what’s best for both of them—this episode ends with those roles reversed yet again. Pamela tells Louie what he wants, and what’s best for him. Breaking up, she says, is the best thing she can do for them both. It’s a wrenching scene (and I suspect it will eventually show that Pamela’s just as guilty of the kind of paternalistic overreach Louie was guilty of in Season 4), but it’s entirely consistent with the dialogue between these two characters and the larger arc Louis CK’s created over these two seasons.

The makeover-as-trope is a notorious false friend. It’s supposed to reveal a character’s inner beauty by—paradoxically—covering him up. It’s the kind of superficial transformation that’s intended to render lovability visible. On that understanding, its failure here makes sense: Louie is nothing if not a long deconstruction of that trope. Pamela loved him before this; the revelation of this particular makeover was that it made Louie lovable to himself.

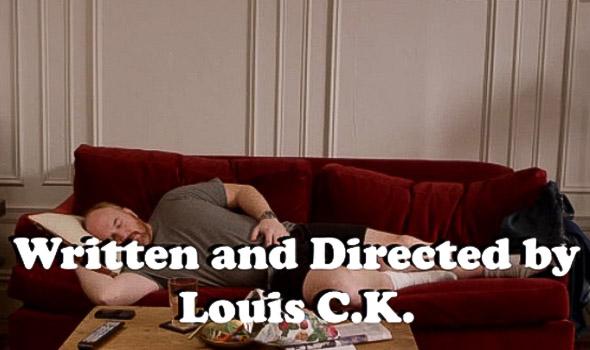

Remember the doll? We last saw it as a bearded bald disaster being made up by Louie’s inexpert hands. It reappears as a perfect restoration of the factory model while Louie watches his daughters exhaustedly from the couch. Makeovers are miracles, but in the real world, they don’t work; whatever our hopes, it would have been disappointing and pat if Pamela’s makeover of Louie in her own image had yielded a magical happy ending, if the show’s solution was for Pamela to “fix” Louie just as he fixed that doll. Love, according to Louie, doesn’t seem to be about the narcissism of making someone over in your own image any more than it’s about grabbing and taking what you want. Love, like so many of Louie’s efforts, frequently fails. But still: It matters that Louie spent Season 4 watching the women he loves sleep on red couches. It matters that, by Season 5, he’s sleeping on a red couch himself

Screenshot via FX

Screenshot via FX

Screenshot via FX