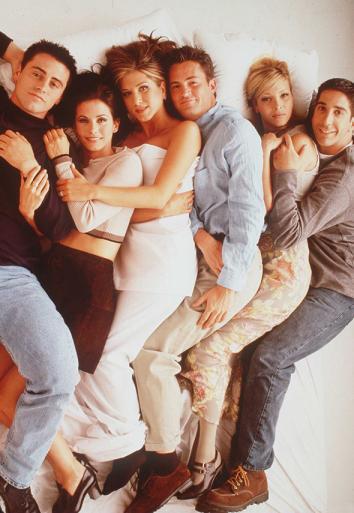

Twenty years ago this week, Friends premiered. The show about six pals who hang out all the time debuted to middling reviews and OK ratings before becoming a gargantuan hit and phenomenon. Friends was a top-10 series for its entire run, and a top-five series if you discount the first season. It always averaged more than 20 million viewers and had 25 million as late as its eighth season. It spawned a haircut fad and dozens of mostly mediocre copycats. Between TBS and Nick at Nite, it is currently rerun eight times a day. The anniversary of its premiere has been greeted with untempered enthusiasm, even for this era of rampant Internet-based nostalgia. (There’s been little celebration for ER, which premiered the same week, and was a bigger hit, if for a few years too long.) Jimmy Kimmel is staging mini-reunions, websites are dueling to create the definitive best-episode list, and residents of New York City can now head down to SoHo and get coffee—and Friends merch—at a Central Perk pop-up shop, where poor Gunther will be making appearances and maybe pouring out lattes, like some sitcom Sisyphus.

The almost entirely positive nostalgia trip surrounding Friends is a little curious— and I say that as a devoted Friends partisan. The show ended just a decade ago, and when it did it was a kind of shorthand for that which is popular, likeable, and unchallenging: pure TV pop. It was a show about white people living in oversized apartments they definitely couldn’t afford in a New York City populated by so few people of color that all the ones with speaking parts could be easily assembled in a single, rhyming YouTube video. Compared with punchier, sourer, more cynical sitcoms—from All in the Family to Seinfeld to The Office—that found humor in humanity’s bad behavior, Friends was smiley and conflict-averse to the point of being featherweight.

The show’s Thursday night partner, Seinfeld, was famously about “nothing,” a claim that, especially in the context of Norman Lear’s morally instructive, socially aware series, was a kind of nihilist cri de coeur, a pledge with philosophical as well as comedic heft. Friends took Seinfeld’s nothing and its ancillary “no learning, no hugging” rule to heart—and then put the hugging back in. It did more than any show to excise the teachable moment from sitcoms for grown-ups: Friends occasionally ran up against “issues,” including lesbian mothers and weddings, but always treated such matters in a casual, offhand manner. It was a show without take-home lessons that was as cute and sweet as any show with them.

When it ended, critics, even those who liked it, struggled to find the words to celebrate it. Heather Havrilesky, writing in Salon, channeled the sort of “yes, but” spirit of loving Friends: “Yes, Friends was silly and sentimental and self-important and fluffy at times. But isn’t that an indelible part of what we liked about it?” Time’s James Poniewozik wrote that unlike most other great sitcoms, Friends “is simply about being a pleasant sitcom.”

But in the decade since Friends ended, it has become clear just how hard it is to make a straightforwardly pleasant sitcom, one that 20 million people want to watch and discuss. What Friends did so effortlessly has become, noticeably, very difficult. (Parks and Recreation, a sweet and funny show starring a very talented cast, can’t reliably attract 4 million viewers.) Nostalgia demands that we see the past through rose-colored glasses: The aggravating and the annoying, the painful and the piercing, these things fade away, leaving us with a soothing memory of a more carefree time. But Friends really did begin in a more carefree time. It was the quintessential Clinton-era comedy, existing in the historical period between the end of the Cold War and 9/11—even though the show went on for three more years, into 2004—and in a TV era when the networks could still reliably mint mass-appeal sitcoms. No concern—sandwiches, pet chickens, naked neighbors—was too small when times were so good.

The tug of nostalgia is strong, but Friends, which was “nothing more” than a very funny, anxiety-free sitcom starring a supremely talented cast, almost doesn’t require nostalgia to be glowingly appreciated from this particular vantage point: The pure pleasure-giving sitcom has never been a rarer thing. (Nostalgia, or memory loss, is required to forgive the dreaded Rachel-Joey romance.)

* * *

The pilot of Friends was not particularly well-reviewed, but it plays well in hindsight. It begins with the gang, sans Rachel, hanging out at Central Perk, endlessly chatting, one conversation fading out and another fading in. The group talks about Chandler’s dreams and Ross’s divorce with a chatty, wannabe art-house cinema vibe. This discursiveness wouldn’t last, but most of the characterizations would: The sarcastic, neurotic Chandler, too-reasonable Monica, space-cadet Phoebe, and lovelorn Ross are all here, more or less fully formed. Only Joey, more of a meathead in the early going, would really transform, into someone more sweetly stupid.

And then into Central Perk walks Rachel, in a wedding dress, demanding and spoiled, incapable of making a cup of coffee or living without her father’s credit card. As the show went on, the characters leaned into their quirks, or grew new ones—Ross developed his paranoid-frantic physical-comedy side, Monica’s OCD got shrill—except Rachel, who grew out of hers. Aniston has spent the last decade being a celebrity and the star of mostly middling movies, but her Rachel is a towering comedic performance. She took a cliché—a ditzy JAP with a nose job and no sense of responsibility—and exploded it, keeping Rachel funny while turning her into an everywoman, the only character not reducible to a tagline.

Unlike with so much contemporary TV, there is no barrier to entry with Friends. Do you like to watch attractive people being funny while doing amusing and sometimes romantic things? Do you want to hang out with people who feel like your own friends? Think about the current comedy universe—which Friends, with its eight episodes a day and with Aniston, especially, still all over the tabloids, arguably inhabits. Some critically acclaimed comedies (Louie, Girls) are barely concerned with laughter, and can cut more painfully than the most poignant dramas. And series that center on a group of friends are often alienating in their generational exactitude. The characters on New Girl are older than those of Friends were, but they’re even more childlike. The best Friends copycat of all, ABC’s canceled Happy Endings, played like a feverish generational in-joke.

These shows have absolutely no truck with broad—specificity is what they are all about. This, especially in the case of Girls and Louie, is an artistic choice, but it also reflects the larger TV landscape: Regular viewers may not care very much about the general collapse in TV ratings, but the kind of shows that get made now—series aiming at ever smaller, hopefully passionate demographics—reflect the drying up of a large general-audience pool. This has given us lots of great, edgy comedies, but it has also given new network comedies a light sheen of anxiety—they have to do everything they can, right away, to find an audience—and a tough choice: Should they be unbearably broad, in the hopes of attracting everyone, or self-defeatingly narrow, in the hopes of inspiring the passion of the cool kids? In comparison, Friends is wonderfully relaxed, casually assuming it has a claim on your attention even when it has made an entire episode about Ross’s misguided leather pants or the time the gang was going to be late.

Friends has an inviting, welcoming air. The only thing it is really specific about—the only thing it needs to be really specific about—is the friends themselves. The best episodes exist entirely within the fictitious world the show created—episodes set entirely in Monica and Rachel’s apartment, for instance, or with video flashbacks to their lives in the ’80s or trivia contests featuring questions only about each other. This is the reason it has aged so well: Not only is it relatively timeless for a sitcom, watching Friends turns you into a friend, initiated into the ins and outs of their relationships and personalities, their inside jokes, the PG way to flip somebody off.

Different viewers find pleasure in different shows, but pleasure is the only reason that most of us watch TV at all. And yet pleasure is often the elephant in the TV room: Describing something as merely pleasurable seems like a knock on it, a sign of some fundamental superficiality. (It is the fallback explanation for watching reality TV, after all.) Twenty years after it started, Friends reliably, effortlessly delivers more pleasure than most contemporary sitcoms. Good jokes, no stress, great company, soul mates who end up together forever, just like lobsters? Let’s go watch it again.