Wondering what will happen next is a natural response to any good piece of serialized narrative art. Between chapters of Crime and Punishment readers likely gathered round the samovar to trade speculations on the fate of Raskolnikov, with a full month for their theories to foment. The nature of the whodunit—or whydunit, in the case of Dostoevsky—is to perpetuate that question, to lead readers and viewers down various garden paths before slicing up the middle with the truth.

So it’s not surprising that much has been made of solving True Detective—not just who (or what) is killing all those women and kids, but the various riddles of the show itself. After io9 tipped everyone to the show’s literary touchstones, there’s been something of a Web-wide race to figure out how those references might indicate where things are headed. “Decoding the secrets of True Detective,” one headline reads. “How do you think True Detective will end?” asks another piece. And many publications, including this one, have dedicated panels to not just analyzing what we’ve seen so far but predicting what’s to come.

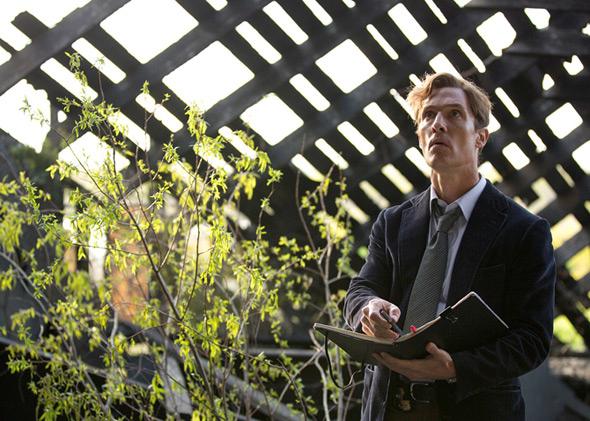

Guessing games can make for a decent way to burn time between episodes, but they seem to have obscured what kind of show True Detective actually is. From its schlocky title, to the expositional conceit of complementary (and contradictory) police interviews, to the various ways in which viewers are treated as detectives alongside its heroes, the show is highly self-conscious and frequently metafictional. Unlike its superficially similar contemporaries, The Killing and Top of the Lake, it’s less about the pursuit of a solution than an exploration of storytelling itself. As a work of television, it might be best understood as parody.

That word tends to evoke, say, Hot Shots Part Deux or anything featuring Leslie Nielsen. But True Detective calls to mind the “more human and capacious modes of parody” that the critic Michael Wood has described in writing about Thomas Mann. Books like The Magic Mountain and Dr. Faustus, Wood argues, “invisibly hollowed out rather than brilliantly exploded” notions of what a novel might do or be; as a parodist, Mann’s work was never a lampoon, but a subtle travesty of the form. Another useful point of comparison is Vladimir Nabokov, who viewed parody as a game, a riddle, something in which one might participate and play. Think of the anagrams that dot Lolita, or the sly, literary Easter eggs scattered throughout Pale Fire.

If we think of True Detective as a parody in these terms—that it nods toward certain conventions only to manipulate and muddle their strictures and codes—it might coax us out of our pursuit of trajectory and meaning, and ultimately help us appreciate the show more on its own terms. “I think we’re doing a good job of telling the story that this genre demands,” series creator Nic Pizolatto told the Daily Beast. “I think we’re also poking certain holes in it and looking at where these instincts begin, both in the type of men that Hart and Cohle represent—and in ourselves as an audience.”

Maybe a reading of True Detective as so intentionally self-conscious feels generous. Certainly elements of the show border on just plain hackneyed, from the bickering cop duo at odds with their boss (“We need more time!”) to the too-familiar opening image of the entire series. (How many episodes of Law & Order: SVU have begun with that same, nameless, naked dead girl, minus the antlers?) The requisite “gun and badge” moment in Episode 6 (echoed when Marty sheds his own gear to dust it up with Rust in the parking lot—they’re the same!) never really stepped outside the prescriptions of the same scene from every police procedural ever. And if True Detective’s vapid gender dynamics are intended to comment on the ways in which women are often depicted in these types of stories, they have yet to ripple, let alone puncture, the veneer of those portrayals. (The ex-hooker Marty screwed in Episode 6 should be cause for an eye-roll and a sigh.)

But the show clearly strives to remain aware of the familiarity of its material—and to play around with that familiarity. Its self-consciousness becomes evident when characters appear to be speaking directly to viewers—most obviously in Rust’s quasi-metaphysical interrogations of chronological narrative. “Time is a flat circle,” he mutters, right after describing this world as a place “where nothing is solved.” Pizzolatto has claimed that this speech could well be “a character in a TV show railing against his audience.” As direct address, it’s more subtle than the talking-to-the-camera moments in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, which were both a recognition of artifice and a ploy for intimacy, and less of a purely aesthetic choice than the Shakespearean soliloquies of House of Cards. Here there’s no fourth-wall rupture: Marty stays in character, and the statement’s real-world echoes exist only for the viewer.

There’s at least one precedent for something similar on TV: Twin Peaks. As Molly Lambert has noted on Grantland, it too was a small-town murder mystery with dalliances in the supernatural, and it invoked certain tropes (e.g., the naked dead girl opening) only to resist or fracture the anticipated outcomes. It was also, essentially, about watching television. Both shows have likewise aimed for a more experiential than teleological response from viewers. “The most satisfying part of a mystery is rarely its resolution,” Lambert writes. “Sustained anticipation is much of the thrill.”

Every time True Detective hits an expected mark—the apparent discovery of Dora Lange’s killers, for example—the story, instead of moving toward resolution, seems to unravel even further. (Each major plot-point, in Pizzolatto’s words, “keeps subverting [previous] subversions.”) Back in Episode 3, the 2012 testimony of Rust and Marty started to diverge from what we were seeing in flashback; in Episode 6, when the former partners finally reunite, the past catches up to the present. One might expect this point of confluence to correspond to some renewed narrative certainty and direction, but I, for one, am more (happily) bewildered than ever. In fact, it was in the week since that I’ve become less invested in thinking ahead to the show’s finale than, like Rust and Marty, reconsidering what’s already happened and how we’ve gotten where we are.

If we accept that one of the show’s goals is to align the audience’s experience of the events onscreen with the murder investigation, retrospection feels like it might be one of the intended responses. Detective work, after all, is less about projection than revisionism; the solution to any mystery is only the sum of its historical parts. Yet in forcing us to look back, True Detective seems to be attempting to conflate the experience of past, present and future—to flatten the circle of televisual time—both for its characters and viewers.

Pizzolatto has told the Wall Street Journal to expect that “the show’s agenda won’t be clear until the eighth episode has ended.” It’s a worrisomely pedantic-sounding statement; some pat lesson or takeaway risks compromising what’s most compelling about what we’ve seen so far. For two more weeks I will be happy to watch, and to try to focus on more immediately compelling things about True Detective than who killed whom or which state official will end up being the biggest Satanist. What Thomas Mann’s novels resisted, according to Michael Wood, was “sterility or the endless repetition of old forms.” Thankfully, one show, which really is unlike anything else currently on TV, is trying to reinvigorate those old forms through parody, and getting us to play along.