The very first shots of the very first episode of Breaking Bad were so bright and clear, they almost hurt your eyes. Cacti, rock formations, a mesa, and then Walter White’s famous pair of billowing, belted khakis silhouetted against a cerulean sky, objects of such stark clarity and solidity they looked as though you could snatch them out of the TV set. Since this start, Breaking Bad’s distinguishing characteristic has been this sort of hyper-reality—not just of objects, but plots and people and places as crystalline as the blue meth Walt and Jesse Pinkman have spent the past five seasons slinging. While other great dramas hew to murky syntax, opaque motivations, suppressed emotions, Breaking Bad has always been a creature of the desert, operating in direct sunlight. Its arc was stated (Mr. Chips would become Scarface), its morality expressed (a man really can break bad, and that’s not good), and its characters etched as lucidly as those pants against the sky. We know intimately who Walt and Skyler White, Jesse Pinkman, and Hank Schrader are, even though we don’t know, always, what they will do, or what will be done to them. Breaking Bad is as psychologically exacting as it is outlandishly thrilling, complex, intricate, and heart-stopping, but it has never been mysterious: The only real mystery—and it sets my nerves jangling just thinking about it—has been how it will end.

When we left off, Walter White, deep into the rococo phase of his megalomania—a giveaway symptom of which is spouting Destiny’s Child lyrics with a menacing leer on one’s face—had decided to walk away from his life as a drug lord. Having recently arranged the prison murders of nine men and having personally killed Mike Erhmantraut, Walt had no enemies left to vanquish, no competitors left to squash. He could go clean, even if it was way too late to go good. Had Walt any challengers remaining, he might not have quit. His competitive drive and egomania is such that he would never finish on anyone else’s terms. But with all immediate, noncancerous threats dispatched and so much cash on hand that silverfish were sure to take much of it, he let Skyler convince him to get out of the business. And then his DEA brother-in-law Hank, motivated by a once-in-a-lifetime desire to read poetry for fun, finally realized Walter White was not his mild-mannered confidant, but the highly dangerous drug kingpin he had been tracking for years. Walt has worked all the way up the chain of adversaries from scumbag to drug lord to honest-to-god good guy. The final confrontation is at hand.

In the first episode of the new season, Hank’s reaction to this revelation is visceral: It makes him physically sick. But if you go back to the first season of Breaking Bad knowing what you know now, you can see Walter White’s worst qualities simmering inside him all along. Walter White was once a law-abiding chemistry teacher, disrespected in his classroom, emasculated in his own home, beset by cancer and credit card bills, and motivated by a desire to provide for his family. But he was also a keeper of secrets and nurser of grudges, a spectacular liar with an explosive and violent temper, a man with a predilection toward emotional and sexual bullying, nursing the deep belief that he had been wronged and overlooked by the world.

At first his behavior seemed badass: beating up a jerk who teased his son; blowing up an insufferable rich guy’s car; returning home at the end of the pilot having murdered two men in an RV to take Skyler from behind (“Is that you, Walt?” she asked). Or it seemed explicable, at least: choking a man to death after less than a week on the job; trying to force his wife to have sex with him against the refrigerator post-murder; obsessing about meth craftsmanship. But these were just harbingers of more unhinged, ruthless actions to come. We underestimated Walt by overestimating him, seeing good intentions where there was also always his thrumming, humming, unquenchable need to be recognized.

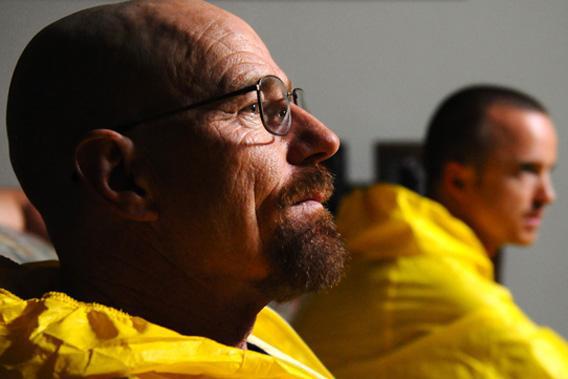

For many seasons, the sheer charisma of Bryan Cranston’s performance kept viewers on Walt’s side, even as we watched him poison a small child and let a woman choke on her own vomit. No actor has ever lied so well on camera—been simultaneously so transparent to the audience and so believably opaque to his peers. But the writers’ view of Walt eventually won out. Breaking Bad has enormous sympathy for the ethically compromised. The show wants us to feel for Skyler, who is now deeply engaged in laundering drug money; for Mike, a problem-solving multiple murderer; and, most of all, for distraught, disturbed, haunted, drug-dealing, people-killing Jesse. But Breaking Bad has no truck with Walt’s pride and self-delusion, his amoral quest for immortality.

Breaking Bad, like all truly great shows, is an endlessly rich text. Among many other things, it is a dark comedy about Marxist alienation and DIY culture, a tragedy about the precariousness of middle-class life in America, a riff on global business practices, scenes from the disintegration of a marriage, and a thrilling action adventure. But most simply it is about a man steroidally, homicidally motivated not to die of no importance. Walter White, like every tyrant and also every selfie-taker, just wants to be—as the tagline points out—remembered, and as more than a regular guy and by more than just those who love him.

What Walt wants, much more than money, is long-term infamy and respect. He cannot have that. The flaw of Walt’s ambition is built right into the command “Remember My Name.” The name that Walter White wants everyone to recall is Heisenberg, and that name already belongs to someone else. Walter White has perverted and poisoned his life, and the life of everyone around him, to construct an “empire” in someone else’s name, built on the only thing less stable than sand—speed. Not just the blue stuff, but the stuff of time itself, which Walt is running out of. Walt has made himself a myth as if that could sustain his life, and that is the biggest self-delusion of all.

Writing in Time, James Poniewozik rightfully argued that, as it sprints toward the finale, it’s not Breaking Bad’s job to punish Walter White: “It’s important, and necessary, and unavoidable, that we should ask what Walter White deserves,” he writes, “But it would be a mistake to decide that Breaking Bad has a responsibility to give Walter a just punishment—that it owes it to him, and to us, and that if it doesn’t … then Breaking Bad is a bad show, both dramatically and morally.” But Breaking Bad’s high-wire plotting works so in concert with its ethical outlook that almost all of the show’s many possible outcomes—Will Walt kill Jesse or Hank? Will he die? Will he kill Jesse or Hank and then die? What will happen to his family? Will he succumb to cancer? Will he have to go back to teaching chemistry? Will he thrive?—mete out punishment to Walt, even if it is not as much as he has earned. Justice always finds the man who thinks that he can live forever. It will find Walter White, too.

Catch up on Season 5’s first eight episodes: