In 2007, AMC was best known for what it was not: not the theater chain that shares its name, not a place for original content. The fledgling channel had broadcast one homegrown Western and was still mostly airing American movie classics when it premiered Mad Men that year, and then, a year later, Breaking Bad. Just like that—one, two—AMC made excellent television look easy. It is not. AMC has spent the five years since making it look much harder. Its new crime drama, the stifling, dreary, enervating Low Winter Sun, which premieres Sunday night right before Breaking Bad and does not benefit from the comparison, makes it look hardest of all.

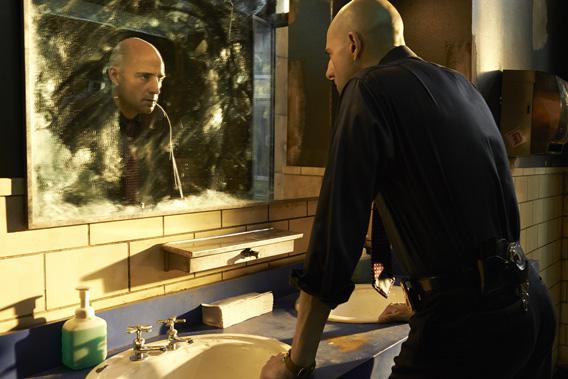

Let’s take out the Quality-TV Cliché Checklist, spread it on the table, rub out the wrinkles, and begin: Low Winter Sun, based on a two-part British miniseries of the same name, opens with the show’s leading man, Frank Agnew (Mark Strong), drinking too much in order to gin up the courage to murder someone (antihero, check; violence, check). Frank is a cop in Detroit (specific geographic location that hints at the squalid inner life of its characters, check) and the man he is about to murder, Brandon, is also a cop, a dirty one (moral ambiguity, check). Frank’s accomplice, another detective named Joe (Lennie James), insists that Brandon brutally slaughtered Frank’s maybe-prostitute girlfriend (sexual violence, check; antihero with a soft spot for prostitutes, check). Frank and Joe do the deed beneath a flickering fluorescent light and, to the strains of a rock song that sounds something like the Rolling Stones covering “A Day in the Life” (Scorsese and Mad Men influence, check, check), try to make it look like a suicide. The next morning, after we see that Frank lives on a street where every house but his is abandoned (ruin porn, not a quality TV cliché, just a Detroit cliché, check), he arrives at his decrepit precinct, just ahead of internal affairs, in the form of Breaking Bad’s very own Gale Boetticher. IA was investigating Brandon, whom they can’t locate. Frank becomes suspicious that Joe, who was Brandon’s partner, might not have been telling him everything (who can you trust?, check), even as he is tasked with finding the murderer of the guy he murdered. All of this is filmed in really, really low light (darkness, check).

The show that Low Winter Sun is most obviously indebted to is The Wire. Like The Wire, it wants the city it is filmed in, Detroit, to be a “character,” but unlike The Wire, it seems to know only the stereotypes about Detroit: dangerous, dying, once great. The comparisons to The Wire don’t end there: The show’s major B-plot focuses on Damon, a tough but soulful white guy, and his all-white crew, trying to come up in the drug world. (Low Winter Sun employs a number of black actors, but it is still remarkably white for a show set in a city that is 82 percent African-American.) Damon is played by James Ransome, a David Simon regular who starred on the second season of the Wire as Ziggy. (He’s grown up since then, filled out and broad shouldered—quiet and macho, a man to Ziggy’s twiggy, antic adolescent.) Low Winter Sun is aware of Detroit’s racial politics—Damon’s girlfriend remarks that Detroit is a “black man’s town”—but I wondered if it made its ambitious, handsome, charismatic criminal-on-the-rise white just so no one would confuse him with a member of the Barksdale crew. Though that would be a pretty perverse concern for a show about yet another tortured white guy. (Check.)

We are very deep into the golden age of TV’s copycat phase. Shows that take various parts from series that came before, reassemble them and tada!—it’s Breaking Shieldpranos! —are legion, and not all of them, even, are bad. (Many of TVs best shows use hand-me-down parts, though never just. The Wire itself relied on genre cop show tricks, like getting the squad back together at the start of each season.) The easiest way to tell the difference between the good and the bad doppelgangers is to apply a modified-for-TV Turing test: Do the characters on screen resemble actual human beings? The hard-boiled, stressed out, depressed types on Low Winter Sun do not. They all seem to be suffering from the same malaise, one that makes them violent and miserable and likely to conduct all conversations in stage whispers.

In the show’s first few minutes, Joe, encouraging Frank to go ahead with the murder, lectures: “Folks talk about morality like it’s black and white. Or maybe they think they’re smart and when they’re at a cocktail party acting pretentious they say it’s grey. But you know what it really is? A damn strobe, flashing back and forth, back and forth all the time, so all we can do is try to figure out how to see straight enough to keep from getting our heads bashed in.” Low Winter Sun is at that cocktail party. It is delivering, yes, a pretentious speech about morality by way of introducing itself, one that sounds self-aware, but is just nonsense: Morality is a strobe? That keeps bashing people’s heads in? Maybe that’ll convince the drunk, grieving guy, but he’s the only one.

Last week, The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum tweeted that a reliable mark of a great drama is that it is, on occasion, very funny. She didn’t identify it by name, but 10-to-1 Low Winter Sun was the seed of this particular insight. In every instance, even in the scenes that are supposed to contain jokes, it is entirely without humor. It tries to make up for what it lacks in originality with unending bleakness—Malick shots of a mangy dog running through the streets with a rat in his maw, characters who never smile—as if being relentlessly somber were proof of quality. The results are beyond claustrophobic. All the characters want out. So did I.