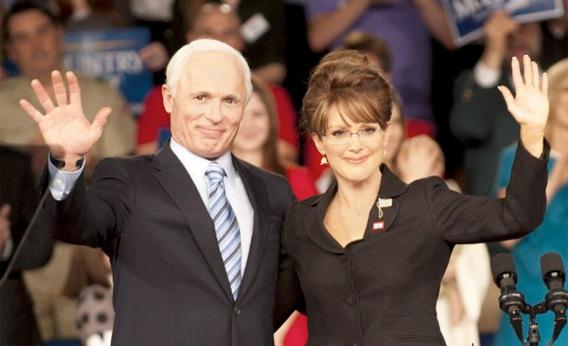

Danny Strong—the screenwriter of Game Change (HBO, Saturday at 9 p.m. ET), a brisk film extracted from the campaign-trail saga of that title—has delivered to Julianne Moore the meatiest role of her career. In turn, Moore, directed by Jay Roach, has aced the immodest task of humanizing the media beast called Sarah Palin. The real Palin (an ignoramus who condemned this nonideological film sight unseen) is a born star; Moore’s Palin is a victim of American politics, just like us. The performance is so compassionate that anyone with an imagination will feel her terror as a deer in the Klieg lights of the national stage. A militant atheist could admire this Palin’s religious faith. Moore makes a good liberal’s heart bleed.

Game Change begins and ends with snippets from a 60 Minutes interview, with Roach splicing together questions posed by the real Anderson Cooper and answers offered by campaign strategist Steve Schmidt (Woody Harrelson). The two hours in between these semi-re-enactments thus play a bit like Schmidt’s traumatic flashback. We are not limited to his perspective, but he serves as a guilty conscience and guide—maybe the closest thing Game Change has to a hero.

Heroism, after all, requires courage, and this movie is a study in disgrace under pressure—notwithstanding McCain’s refusal to let the dog-whistles out and use the “dark side of American populism” against his dark-skinned opponent. (Ed Harris plays McCain as a good guy trapped in “a bad reality show,” bubble-wrapped in the hotel rooms of the campaign trail, and isolated even from his own campaign machinery.) The movie picks up steam as his campaign is losing its own. “We desperately need a game-changing pick” for the Veep slot, says Schmidt. It’s not the smoothest line in the film, nor is it the clunkiest. (That would be, “Now I know why they call her Sarah Barracuda.”) But Game Change’s exposition-through-dialogue and its rewarmed morsels of sound-bite go down smoothly compared to the wads of recycled newspaper that clotted the earlier Roach-Strong collaboration Recount.

In any event, for a game-changing pick, the campaign decides to pander to women, and this account has it that discovering Palin was like discovering a total unknown at the soda-fountain counter at Schwab’s. Watching footage of the governor of Alaska on YouTube, one advisor exults, “She’s a star!”, as if she hadn’t been buttering up the Republican pundits since the summer before.

Early on, as Palin gets called up to the bigs, rushed through vetting and hustled onto the trail, Moore communicates an earnestness that is touching and an eagerness to please that makes you feel sympathetic toward Palin—even and especially when that eagerness is faintly pathetic. Elsewhere, hugging Down syndrome kids on a rope line and dandling her own on her lap, Palin is downright inspirational. And Moore amplifies the governor’s sexual charisma in a way that I shall need to discuss with my shrink. She wins you over.

Meanwhile, Schmidt and his colleagues do excellent muted-reaction-takes at early hints the woman is fundamentally unprepared for the task at hand. They’re wincing at their own fading principles and grimacing with indigestion at the bullshit they have forced themselves to swallow. You admire Mama Grizzly’s protectiveness when Palin expresses anguish at what the press does to her pregnant daughter. You admire nobody when, to soothe her, Schmidt says, accurately: “News is no longer meant to be remembered.”

The scenes that will clinch Moore’s Emmy are in the second act. As it becomes apparent to McCain’s team, via briefing sessions, that she is a know-nothing, they prep her on hot-button foreign policy issues—informing her that we fought Germany in two world wars, for instance. Here, Moore’s Palin takes notes with a diligence that at once enriches the farce and deepens the tragedy. After it becomes apparent to the world, via Charlie Gibson and Katie Couric, that she is a know-nothing, the camera tightens on Moore’s face at canted angles during subsequent tantrums, and we understand her resentment and paranoia. We can’t laugh at the surreal scene of Moore’s Palin watching Tina Fey’s Palin on SNL because the woman alone in front of the set is so, so far away from home—and farther yet from the first-born son who is away at war. He is prepared to die for a nation where she is a national laughingstock. Watching Palin escape a depressive funk by going to sleep—curling fetally on an anonymous floor in a hotel a bathrobe—I wished her sweet dreams, and ultimately found myself rooting for her to do well in her debate against Joe Biden.

When she does do well, she shifts modes, and so does the film. Schmidt calls her “the best actress in American politics,” and if you have spent much time with actresses, then you know that, sometimes, their egos become engorged when they read their own reviews.

With that taste of victory, Moore transforms again into a diva/demagogue/rogue. She had been a flawed human; now she’s a political animal. Someone needs to juxtapose footage of a) Moore’s Palin dabbing an impatient finger at her face to apply makeup before a rally and b) Moore’s Amber Waves making a similar gesture while on a coke run with Rollergirl. These are women filled by hollow needs.

Spoiler alert: Obama wins. Palin wants to go rogue and give a concession speech. Schmidt explains that such a thing has never happened in American history and that McCain will deliver a concession speech worthy of the occasion: “It’s not about you. It’s about the country.” But we already know that she, like most people, knows nothing of history, so why should it surprise us that she doesn’t understand? McCain’s parting words to her—an admonition that she not ally herself with “Limbaugh and the other extremists”—is perhaps the most gruesomely ironic line of dialogue delivered down the somewhat arduous home stretch.

But the most heartbreaking issues from the mouth of campaign staffer Nicolle Wallace (Sarah Paulson), who by election night has long since joined Schmidt and the rest of the staff in their new depths of fear and self-loathing on the campaign trail. She has followed her conscience in one meaningful way, and she cries when telling Schmidt about it. The camera can barely stand to look. She says: “I didn’t vote.”