The building of the First Transcontinental Railroad is a great subject for a cable drama; however, on the evidence of the first five episodes of Hell on Wheels (AMC, Sundays at 10 p.m. ET), it is not precisely a good one. The series’ primary setting is the middle of this continent in the middle of the 1860s, not long after the Surrender at Appomattox Court House. But with an early title blaring that “the nation is an open wound,” the setting is, first and last, a sovereign republic of metaphor. Not content to exploit their subject’s inherent themes, the series’ fraternal creators, Joe and Tony Gayton, have adhered them promiscuously, pasting neon Post-it indications of symbolic import in a way that obscures moments of straightforward drama.

Out on the prairie, a fair lady observes that the land “hasn’t changed since Lewis and Clark first saw it 60 years ago”—and then promptly witnesses a raid by natives. Elsewhere, characters divest themselves of con-artistic monologues about Manifest Destiny, rumbling speeches about Reconstruction, paeans to the vast possibilities of America, lilting tributes to the frontier, and homilies on the Promised Land delivered beneath looming crosses. Less frequently, they express recognizable human emotion.

The hero is Cullen Bohannon, played by Anson Mount with a grizzled animality and gaunt humanity that help the character to shoulder the burden of history. Bohannon fought for Confederacy. He was a slave owner, but he freed his slaves before the Civil War began, guided by the influence of his wife: “She convinced me of the evils of slavery.” She also did needlepoint, as we see in a dewy-eyed flashback to the days before Union soldiers raped and killed her. Bohannon has been serving revenge to the perpetrators on the toasty side, and his quest soon leads him to the frontier of the industrial age—to the mobile tent city that followed the railroad’s westward progress from Council Bluffs, Iowa.

The path was long and winding, as dictated by Thomas Durant, who was the vice-president of Union Pacific Railroad and who owned a swath of Nebraska across which the railway uselessly switched back and forth, much to his personal enrichment. Played by Colm Meaney, Durant is a pioneer of corruption, an avid propagandist, a beastly exterminator of brutes, and a fat little florid orator who hogs all the ripest lines. “What is the building of this grand railroad if not a drama?” he asks at one point. He’s practicing a sales pitch, maybe, and presenting a mission statement for sure.

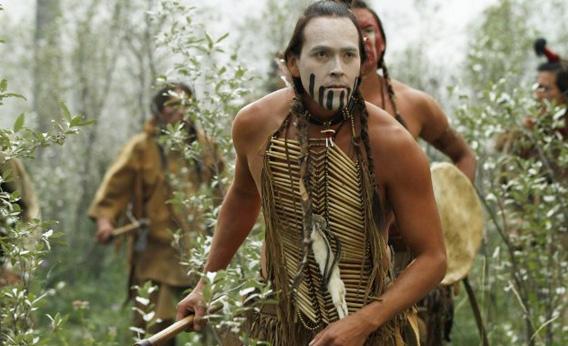

The players in this drama are figures in a panoramic diorama. In its world of mud and sepia, feral whores face down lank preachers, Irish immigrant brothers seek their fortunes, Scandinavian-born enforcers looms as creepily as The Seventh Seal’s Grim Reaper, and noble savages keep on keeping on. Second billing goes to Common, who plays Elam Ferguson, a former slave working for Union Pacific. The actor does a lot of good simmering and dutiful glowering, and his character’s relationship with Bohannon is the richest one on screen. The performance is just good enough to distract you from the fact that Ferguson less resembles an individual than an archetype addressing a few centuries’ worth of racial grievances.

None of Hell on Wheels’ juicy eruptions of pulp or sporadic glimpses of soul impedes the myth-belching progress of a story about the little engine of empire that could. The shots are heavily styled in a way that is variously enrapturing and distancing, taking cues from landscape paintings, Mathew Brady photographs, and revisionist Westerns—all to the end of toying with the old myths of the New World. But you can hardly see the world for the myths, and the show seems bent on encouraging a sophisticated audience to set its intelligence aside in a sophisticated way.

Hell on Wheels

Why can’t anyone on this show act normal and not all mythical?

Chris Large. © 2010 AMC. All rights reserved.

Advertisement