“I’m food bad boy Tony Bourdain,” said food bad boy Tony Bourdain, last Sunday night on The Simpsons. “There’s nowhere I won’t go and nothing I won’t eat as long as I’m paid in emeralds and my hotel room has a bidet that shoots warm Champagne.”

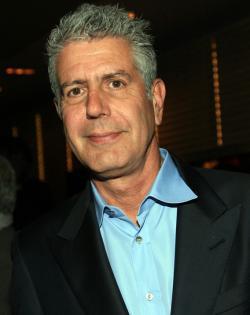

The episode, titled “The Food Wife,” found Marge earning plaudits as “Fun Mom” for introducing Bart and Lisa to the exotic pleasures of Springfield’s restaurant scene. Then she started fretting that Homer—very suddenly eager to trade in his doughnuts for artisanal beignets—would steal her foodie thunder, and a handful of celebrity chefs appeared to Marge in an anxiety dream set at a Singapore food stall. There was Mario Batali sporting his own line of Crocs on his feet, Julia Child wearing her signature pearls, and the Swedish Chef lurking behind his trademark mustache, but foremost there was Anthony Bourdain, pairing sandals with a blazer and fondly parodying his existence as the sharpest knife in television’s drawer of professional gourmands. He presented Marge with a “triple-spicy barbecued stingray stuffed with pig organs” and then stood by, mellowly aghast, as Homie swallowed it whole.

If you enjoyed this scene and are eager to digest more of the same, then tune into The Layover (Mondays at 9 p.m. ET), where Bourdain exhibits a further willingness to present himself as a cartoon. The new show is a lesser cousin to Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations, a travel show that succeeds beautifully precisely because Bourdain proceeds less as the host of a travel show than as the narrator of a compact odyssey. He offers lyricism without preciousness and awe without hype, and his observations about food and culture do something to nourish the soul. Where watching No Reservations is like settling into a riveting essay, watching The Layover is like thumbing through a branded pocket guide.

In the first episode, Bourdain touches down in Singapore for a 30-hour visit, puffy-eyed after a 17-hour flight. The snappy graphics detail how a tourist can take the train in from the airport for two bucks or the bus for even cheaper. Bourdain takes a $25 taxi, justifying the expense by citing an urgent need to evacuate his bowels: “I’ve gotta download the brown file.” In pungent detail, Bourdain then explains why he was reluctant to do so in flight. Long practiced at using his frankness to seduce an audience, the man is now exploring its possibilities as a repellant.

Thankfully, we spend much of our time at the other end of his alimentary canal. Peanut pancakes, wonton noodles, carrot cakes, Hainanese chicken rice—the delicacies fly by. The pace is brisk, hurried, harried. Bourdain is up to ingest anything, except for the liquiform tourist trap of the Raffles Hotel’s Singapore Sling. He declares it “a disgusting drink,” preferring a gin-and-tonic at cocktail hour and a lime juice at any time of day, in a sense: “I had some of that for dinner the other day—for lunch—for breakfast yest—for breakfast today.” Jet-lagged and disconnected, he comes by his crankiness honestly, which does contribute something authentic to the texture of the show. Bourdain moans about being forced, for the sake of continuity, to wear the same outfit throughout the taping: “I smell like I’ve been rolling around in sheep guts.” The equatorial heat does not treat his “asscrack” favorably.

The problem with these moments is not that they’re mildly gross but moderately gratuitous. Is the simplest way for this city-skimming show to convey the illusion of depth to hammer Bourdain’s personality into a persona? Or could it be that Singapore’s authoritarian streak so excites his bad-boyishness that it breaks out like a bad rash? A discussion of the local censoring of Sex and the City turns back to Bourdain’s foul language: “I was published here without any edits at all, and I wrote a filthy, filthy book.” And a discussion of vice laws inspires an unfortunate attempt at a grisly joke told in voice-over: “Ordinarily about now, I’d be beating a prostitute to death, covered in gore and frantically trying to dispose of the evidence. … Damn you, nanny state!” The first installment of The Layover represents a travel show turned out as a piece of performance art, and it misses its connection.