Master of Terror

Maurice Sendak understood that children need to be terrified.

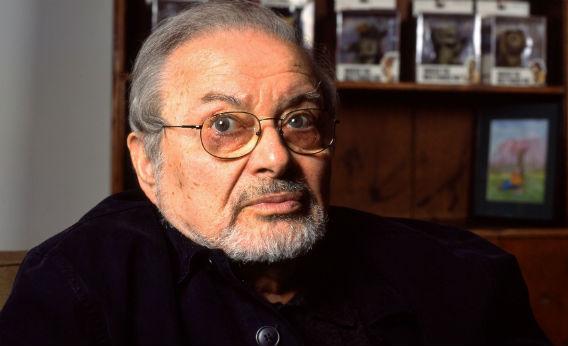

Photograph by David Corio/Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images.

Also in Slate, see Emily Bazelon’s tribute to Maurice Sendak’s particular type of genius. John Plotz explains how Sendak was a creator of crazy worlds.

When I heard that Maurice Sendak died what may or may not have been the “yummy death” he had hoped for, I was, like scores of adults trying to go about their normal adult lives, suddenly transported for a moment back to the frightening and exhilarating dreamscape of Where the Wild Things Are, and In the Night Kitchen. And I wondered, for the zillionth time, why do children love those books so passionately? Why do they become part of us in ways hundreds of other children’s books that are read to us don’t?

Sendak once told a reporter for the Guardian that he was crazy, and that was why his work was so good. It seems to me that part of that craziness, or rather the insight produced by that craziness, is that he wasn’t afraid of writing very dark and disturbing children’s books. In fact, he understood that what children really want is to be disturbed, ruffled, terrified. He wasn’t interested in writing sweet or charming books for children like Angelina Ballerina, or Olivia. "I refuse to lie to children," he said. "I refuse to cater to the bullshit of innocence."

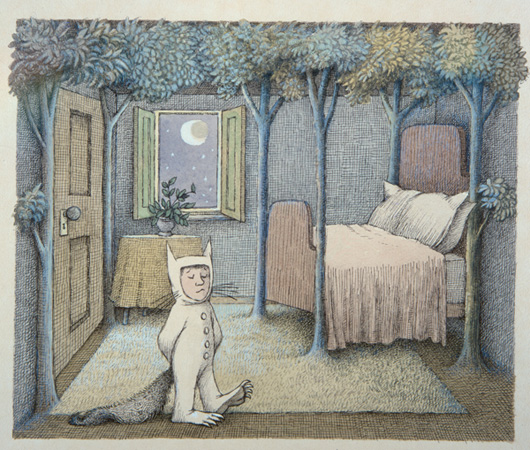

And because of his colorfully unhappy childhood, Sendak seemed to have some special access to the fears and miseries of childhood. There is the moment in In the Night Kitchen when the child falls naked out of his bed through his darkened house, calling for a parent who can’t save him. There are the truly ominous fat bakers, who try to bake him into a cake. There are, in Where the Wild Things Are, the wild things with their terrible claws and terrible teeth, who want to keep him on their island forever. And then there is the impotent, invisible adult world, the punishing or neglectful parents, off the page, who won’t or can’t help. Sendak is taking on the primal, irrational fear: You are not safe in your room.

Of course the tousled boy characters are not killed by mauling wild things or baked in a hot oven by bakers with Hitler mustaches, and the moment that the tousled boy character sails off in a boat, or makes a plane out of dough, or dives naked into the giant bottle of milk is thrilling precisely because the scenario he has escaped is so vividly upsetting. (Sendak’s more recent books like Brundibar, and Bumble-Ardy deal with even more unsettling material, with dead or dying parents and Nazis.)

But the point is that like many great children’s book writers before him, Sendak is writing nightmares, not dreams. (Think of poor Alice in Alice in Wonderland with the Queen of Hearts cutting off people’s heads, or of Charlotte’s death in Charlotte’s Web.) The children’s books that rehearse and access children’s deepest fears or anxieties engage them and fascinate them on a whole different level than those that merely entertain or please them.

Our instinct to shield young children of say 2 or 3 or 4 from upsetting subjects, from death or abandonment, or creatures with big teeth, or bakers that mistake them for milk, may be misguided. It may be precisely the upsetting subjects—the secret terrors, the fear of death or disappearance or abandonment—that they want to see illustrated and pinned down.

Freud wrote about the “fort/da” game of peekaboo, in which children master the absence of the mother. He discusses the thrill of the game, which is pretending the mother is missing (or lost or dead) and the joy of her return. The rehearsal of the child’s great fear somehow soothes and excites him, with a mastery of anxiety, and this idea is something Sendak played with. The child wins, in the end, and is unscathed, but not without a very serious brush with terror, loneliness, angst.

Sendak’s fierce unsentimental view extended even to the nature of love itself, as expressed in the transcendently great line which readers may, this afternoon, say to the grumpy brilliant author himself: “Please don’t go. We’ll eat you up we love you so.”