Last year, in the company of a nurse, a priest, and several homeless men and women from the streets of Boston, I went on a pilgrimage. A short odyssey of the soul: We walked out of the city for 60 miles, sleeping in churches on the way, heading for some friendly monks in West Newbury. One evening, at a church in Haverhill, Massachusetts, a priest who had just joined us offered to read everyone a story. We’d had a long day, we were sitting around rubbing our feet: It was a campfire moment, natural story time. But what story, which author? I was approached by one of my fellow pilgrims. “Tell him, don’t read something that’s all about God,” he whispered urgently. “Tell him to read something about, like, a coyote eating a rabbit.”

I cherish that. It’s what fiction should be, basically, what it should be aiming at: the death-grip, the ultimate concern. The naked lunch. Or as Ted Hughes put it in “Thrushes”: No sighs or head-scratchings. Nothing but bounce and stab/ And a ravening second.

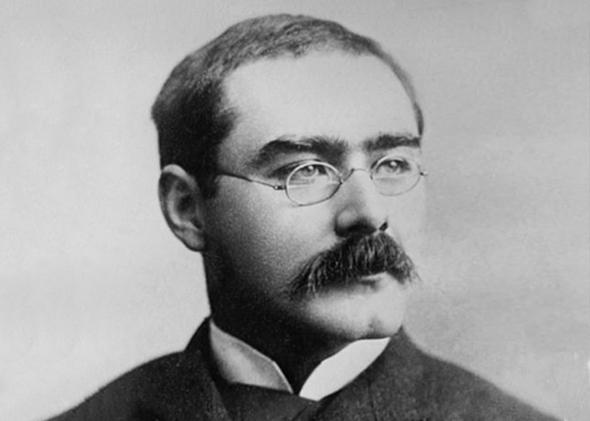

Rudyard Kipling was all about the ravening second. He called it “the undoctored incident”: Oh what avails the classic bent, and what the cultured word/ Against the undoctored incident that actually occurred? This is the wonderful thing about his Jungle Books, which function on one level as a moral primer for imperial schoolboys (Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scout Movement, worked up his Cub Scout catechism from stories like “Mowgli’s Brothers”) and on another level, much deeper, as a sequence of bone-white existential tableaux featuring coyotes eating rabbits. Or tigers eating villagers. Or, as we will be discussing today, mongooses eating snakes.

Rikki-tikki-tavi, eponymous hero of the first Jungle Book’s best story, knows who he is (a house mongoose in India), knows what he’s for (killing snakes), knows his place, damn it, and a bristling unbroken current of mongoose-osity runs right down his ultra-flexible spine. “Rikki-tikki licked his lips. ‘This is a splendid hunting-ground,’ he said, and his tail grew bottle-brushy at the thought of it.’ ” Saved from drowning by a family who have just moved into a bungalow in the “Segowlie cantonment”—a fictional garrison for soldiers of the British Raj—Rikki-tikki becomes sworn protector of the household, and in particular of young Teddy, upon whose pillow he dozes at night, lightly and happily, springing to combat-readiness at the slightest sound. In the bungalow’s explosively fertile garden—“bushes, as big as summer houses, of Marshall Neil roses, lime- and orange-trees, clumps of bamboos and thickets of high grass”—Rikki-tikki encounters the local fauna, including a pair of nasty cobras, Nag and his wife, the lethal Nagaina. After scuffling with this assassin-couple and doing a bit of trash-talking, Rikki-tikki learns of their terrible snakey designs upon his beloved English people. (“Go in quietly,” Nagaina instructs her husband, by the sluice that leads into the bungalow’s bathroom, “and remember that the big man … is the first one to bite.”) So now it’s on: a fight to the death.

“Kipling,” says a psychiatrist friend of mine, “was always pretending to be something other than he actually was—which was a 10-year-old boy.” His work, the best of it, has a boy’s barbarism and a boy’s conservatism. “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” succeeds so spectacularly because it is, in a sense, written by that 10-year-old boy—by little Teddy, the quietest character in the story but the one with whose special boyish loves and terrors the narrative is saturated. The slithering menace to the family; the white, scared faces of the parents; the atavistic intercessor/guardian … Of course “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” is also saturated with imperialist ideology, subduing the alien, etc., Rikki-tikki himself being the emblem of a kind of perfected native servant, house-trained but homicidally loyal. But to read it as an authoritarian fable is to miss the real action of the story, which is down in the unconscious, down with the prima materia, down by the bathroom sluice, where the creepy-crawlies hiss and fiddle and not even Father, the big man, can keep you safe.

Kipling was an instinctive anthropomorphizer—quite a heathen, in that way. He’d give a human personality as readily to a merchant steamer as to a mongoose. It’s the particular triumph of his animal characters, however, that they never become merely allegorical—or rather, they become allegorical while retaining their singularity and animality. Rikki-tikki in his violent happiness represents bravery and battle-joy and life-appetite, without ceasing for an instant to be a mongoose. Chuchundra the muskrat who creeps by the wall (“ ‘I am a very poor man,’ he sobbed. ‘I never had spirit enough to run out into the middle of the room.’ ”) is timidity itself, the unlived life, but he is also a wet-whiskered muskrat in a dark corner.

All of which brings us back to Kipling’s taste for immediate reality, for the ravening second and the undoctored instant. Get enough of that in there, by a paradox, and you will achieve true symbolism. Near the end of the story, having feasted murderously on 24 of Nagaina’s eggs (“He bit off the tops of the eggs as fast as he could, taking care to crush the young cobras …”), Rikki-tikki returns to the veranda with the last egg intact in his mouth—a hostage. “Teddy and his mother and father were there at early breakfast, but Rikki-tikki saw that they were not eating anything. They sat stone-still, and their faces were white. Nagaina was coiled up on the matting by Teddy’s chair, within easy striking distance of Teddy’s bare leg, and she was swaying to and fro …” The paleness and immobility of the humans, the fatal grace of the she-cobra, the suspended threat: It all seems to rise up, like a bad dream, from some prehistoric reservoir of fear.

In the event, at that church in Haverhill, our reader went with “A Father’s Story,” by Andre Dubus, which has a certain amount of God in it and no coyotes. We listened; some of us dozed, shallowly, like Rikki-tikki on Teddy’s pillow. It was a modest victory for literature. Dubus, whose grave is in Haverhill, entertained us in a serious way and perhaps enlarged us. But Rudyard Kipling, I do believe, would have eaten us alive.