The opening seconds of Vince Staples’ Big Fish Theory come on like a trance. A sound that seems to slide between a gust of wind, a police siren, and ambient tape hiss wheezes in the background as a synthesizer plays an ominous progression of minor chords that sounds like something Angelo Badalamenti might drop into Twin Peaks. Fragmentary, blinking tones come in, then a chirping, disembodied human voice. Justin Vernon is credited as a co-producer on the track, titled “Crabs in a Bucket,” but this certainly doesn’t sound like Bon Iver, at least not any more than it really sounds like anything. It’s a startling and transfixing introduction to an album that, by its end, a brisk 36 minutes later, has both confounded expectations and exceeded them.

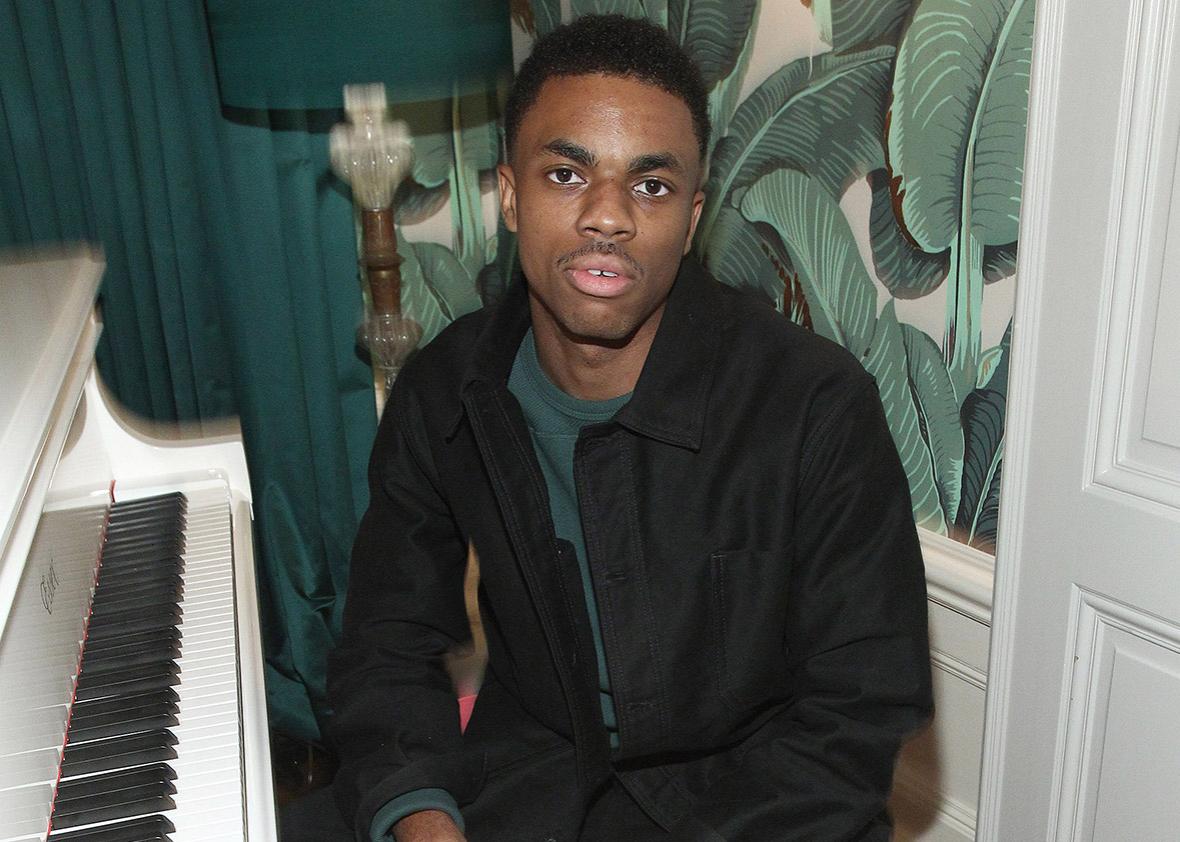

Big Fish Theory is an audacious and genre-defying work, a startling turn from Staples as we thought we knew him. For starters, it’s probably the most rhythmically sophisticated mainstream hip-hop release in recent memory. Big Fish Theory bears traces of Chicago house, Detroit techno, U.K. drum and bass, and a host of other genres and subgenres that in their 21st-century guises have been wrangled under the capacious acronym EDM, or electronic dance music. Tracks like “Homage” and “BagBak” pulse, rattle, and bounce; “Love Can Be …” boasts an honest-to-goodness, EDM-style build and drop; and the stuttering, syncopated tom-toms of “Party People” sound like something you’d be more likely to hear at Ibiza than on Hot 97. Big Fish Theory is only 12 tracks long, a little more than half the length of Staples’ 2015 acclaimed double-album debut, Summertime ’06. Summertime ’06 was mostly produced by Chicago legend No I.D. and was full of terse and percussive beats, the perfect backdrop for a rapper who seemed dedicated to dragging the L.A. gangsta tradition into the present and future.

Summertime ’06 was the sort of album that gets cranky, graying heads nodding in approval for its signifiers of “real” hip-hop; Big Fish Theory is the sort of album that will likely piss off some of those very same people. The lion’s share of these tracks was produced by 21-year-old Angeleno Zack Sekoff, a SoundCloud EDM prodigy, and Big Fish Theory often feels as much Sekoff’s album as Staples’, with tracks functioning as entire soundscapes in which the vocals are simply one instrument among an orchestra. As such, Big Fish Theory bears a glancing resemblance to Atrocity Exhibition, last year’s great LP by Staples’ fellow Joy Division enthusiast Danny Brown, although without the nightmarish, chemical hallucinations of Brown’s work. (Staples doesn’t even drink.)

Staples’ nonmusical vice of choice is basketball: He’s a full-fledged NBA nut, a lifelong Los Angeles Clippers fan, and a vocal hater of the team’s star point guard, Chris Paul. As an MC, Staples shares a wealth of stylistic affinities with CP3, though: He’s brilliant, prickly, and boasts an attention to the details of form that minimizes the self so effectively that it becomes its own rare brand of self-effacing virtuosity. Staples is a genuinely hilarious dude, as anyone who follows him on Twitter can attest, but for all his approachability, his music is unlikely to inspire the sort of personality cults that surround Drake, Kendrick, or Kanye, and Big Fish Theory won’t beget the think-piecing and politicking by proxy that those artists do. For all of Staples’ affable outspokenness, his public statements on Big Fish Theory have often been mischievously opaque. Back in May, Staples described the album as “Afrofuturism,” then a few weeks later claimed he was trolling, telling The Daily Show’s Trevor Noah that “I like saying stuff about black people to white people.”

Big Fish Theory is an album of hip-hop music that requires us to approach it as music first and foremost, in a few senses. Staples is a great rapper, but this isn’t an album made for the online exegetes at Genius, and it’s also a work that’s best entered after you’ve checked your genre expectations at the door. Big Fish Theory isn’t a record that stands still, nor does it ever really seem to do the same thing twice. It boasts a raft of guest stars, but their contributions are woven into the patchwork seamlessly. Luminaries like Vernon and Damon Albarn are present in the album’s credits but almost undetectable. By the time Kendrick Lamar pops up on “Yeah Right” the presence of another rapper is almost startling. And one of the album’s most striking tracks barely features Staples at all: “Alyssa Interlude” opens with the spectral voice of Amy Winehouse from a 2006 interview, talking about love as a quietly pattering drum beat races behind her. As she slips away, Staples appears for only a blurry half-minute before giving way to the late, great David Ruffin, lead singer of the Temptations, intoning their 1967 smash “I Wish It Would Rain.”

The album’s final track, “Rain Come Down,” sends it out on perhaps its highest note. The opening moments belong to the great Ty Dolla Sign, intoning the phrase rain come down in a weary auto-tune. Throughout the song, the meaning of the phrase seems to shift, from weather to bullets (“take a ride on my side, where we die in the street/ and the cops don’t come for some weeks”) to strip-club currency (“Make it rain in the club/ Don’t you dream on how it feels to be in love?”). By the time Staples’ last lines roll around—“What you drinking? Need a buzz?/ Don’t drown in the brown, just drown in the sound”—it feels like a mission statement for the entire record.

Twenty-first-century hip-hop’s relationship to EDM—much like early hip-hop’s relationship to disco—has been complicated and imbued with thorny dynamics of race and class: There’s an unmistakable waft of moneyed whiteness that clings to these scenes, at least in their more spectacular public guises. But Big Fish Theory feels like a significant waypoint in the long-developing convergence of the two forms, a journey that’s lately been helped along by the futuristic Atlanta trap of Mike Will Made It and Metro Boomin, the ongoing musical midlife crises of Kanye West, and, most recently, the instrumental polyrhythmic collages of Indianan footwork producer Jlin, whose stunning sophomore album, Black Origami, released in May, feels like a sort of spiritual companion piece to Big Fish Theory.

Listening to Big Fish Theory also offers a bracing reminder of the degree to which a lot of contemporary hip-hop has strayed from the music’s origins as dance music. I love Kendrick, Drake, and Future as much as (maybe more than) the next person, but there’s a reason young people are still ending their nights dancing to chestnuts like “Hypnotize,” “The Way You Move,” and “Gold Digger.” I’m not necessarily complaining about this, but Big Fish Theory’s emphasis on the bodily pleasures of the dance floor feels like a return to something fundamental, even if nothing else about this album feels remotely like a throwback. The image of the “big fish” usually conjures the setting of a small pond, but the one Staples is swimming in is absolutely enormous. Good thing, too, because he’s an even bigger fish than we thought.