Oh man, boy bands and teen idols, right? They’re milquetoast, manufactured, eyelinered, and sexually neutered cash cows, excuses for tribes of girls to binge and purge on hormonal confusion before they move on to real music and real men. At best, they’re a necessary evil of the pop machine, fodder for future bachelorette-party nostalgia. If they have any genuine talent, they’ll soon enough grow out of the adenoidal simpering, and learn to actually play and write their own songs. Otherwise they’ll end up circuiting the casinos, or face planting into the next poolside platter of coke.

Well, with their latest releases, pop’s top boys of the past half-decade are working to grant their haters’ wishes. They all seem to be pivoting dutifully away from joygasmic affirmation anthems, to satisfy the needs of their maturing fans, more wised-up high schoolers, college kids, and maybe even a few parents—if they’re not simply quitting the field. And for once there seems to be a shortage of dewy dudes in the wings to service the next cohort of tweens. What is the sound of a million girls not shrieking? It’s either the rumble of a gender revolution, or the saddest silence of all.

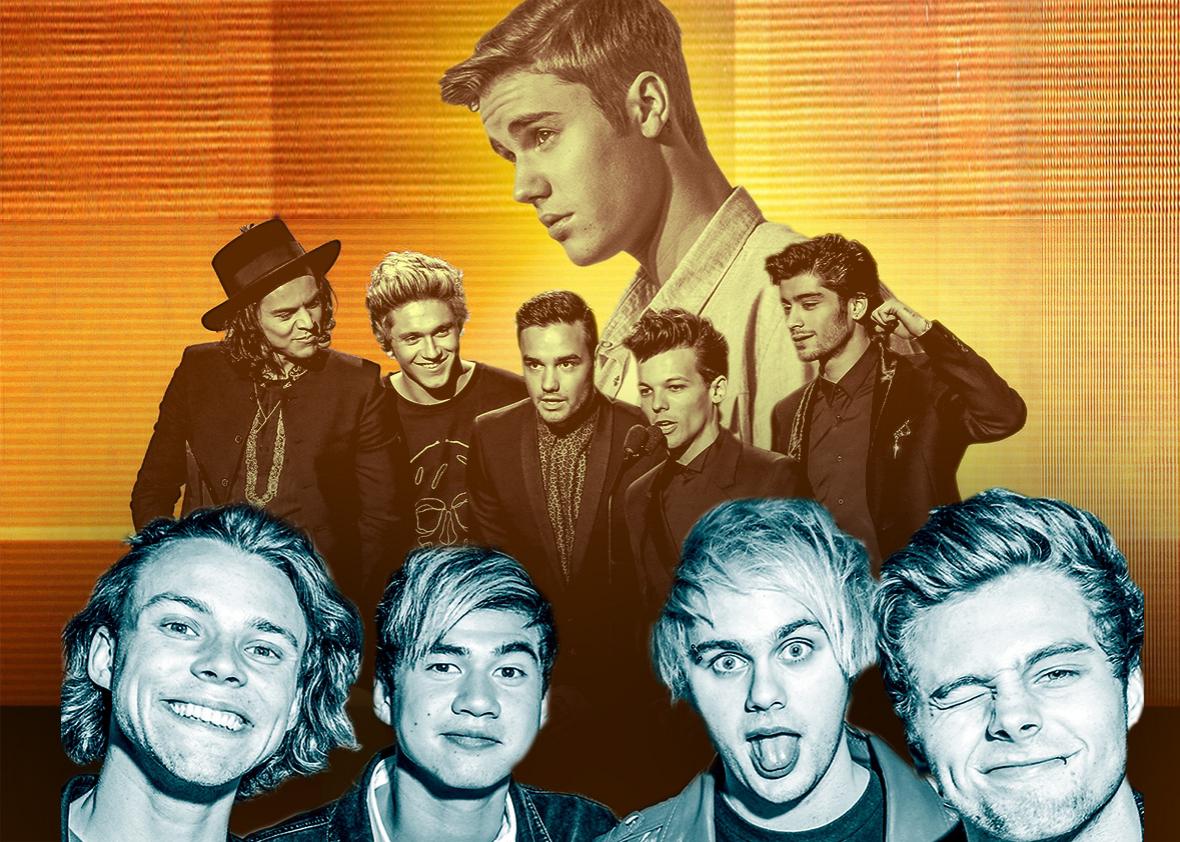

This week’s new Justin Bieber album, Purpose, is an extended hymn of funky penance for the 21-year-old star’s past couple of years of personal rumspringa and sins against Selena Gomez—set to some fairly adventurous beats and elusive electronic squiggles, many of them produced by Skrillex. But you probably know that, if you’re even a casual pop listener, thanks to its advance hit singles, “Where Are U Now?,” “What Do You Mean?,” and “Sorry.”

Indeed, what’s remarkable is that for the first time so many non-Beliebers are not only aware of what he’s up to musically (rather than just the latest tabloid headlines on mansion eggings and penis pictures), but excited about it, bringing him, finally, his first No. 1 single. As a capper, this weekend his camp released videos for all 13 tracks on Purpose, featuring a formidable ensemble of modern dancers but mostly starving fans’ eyes of the Biebs himself, a choice you’re pretty much forced to call artistic.

Meanwhile, the new album by One Direction is more laidback, less anthemic and (somewhat) less approval-seeking than the ones that rendered the Simon Cowell–assembled British power-pop group the most eligible band in the world, to be chased through the streets and fantasized about in dirty fan fiction. It’s called Made in the A.M., but the sound it most evokes is late-1970s FM radio, with its debts to the likes of Fleetwood Mac and Boston. To my ears it’s also on the duller side for a 1D record, so it makes sense that they’ve announced that it’s their swansong for the time being (fifth member Zayn Malik decamped last spring and is now promising a solo debut). The album closes on a song called “History,” one more patented ode to the mutual awesomeness of 1D and its fans—“the greatest team the world has ever seen”—before they close the multimedia carnival down.

That leaves One Direction’s former tourmates, the Australian band 5 Seconds of Summer, to carry on, with their second album, Sounds Good Feels Good, released in late October. 5SOS has always denied being a boy band at all, however, and on this record the songwriting takes a turn away from giddy consumerism about how perfect a girl looked “standing there in my American Apparel underwear,” to young-adult issues of depression and aimlessness. They’re emulating the past pop-punk bands to whom they’d much rather be compared.

While Bieber’s is the most finely crafted as well as the best-selling of the three albums, 5SOS’s is still the most energetic and fun. Its counterbalance to its bout of the sads is an underdog generational solidarity reminiscent of their peer (and Australasian neighbor) Lorde: They declare themselves and their fans “losers, and we’re all right with that … we’re the kings and the queens of the new broken scene.” (Is the nod to Toronto’s gang of hip guitar slingers Broken Social Scene accidental? Unlikely, when you consider that the same song, “She’s Kinda Hot,” includes the line, “My neighbor told me that I got bad brains.”)

Even One Direction at its peak—while definitely a collection of cute boys among whom each fan can select a favorite—never has stuck to the boy-band formula, if you take that as meaning choreographed dance moves, coordinated outfits, and silky-smooth songs à la the Backstreet Boys or ’N Sync. They sent that whole notion up in their campy 2013 video for “Best Song Ever,” in which they stretched bald caps over their floppy ’dos to mimic record-company types concocting images and moves that the guys reject unequivocally.

One curiosity about 1D and 5SOS, in fact, is that they’ve represented a niche revival of the rock band, at a time when the rest of youth-oriented pop pretty much had abandoned it as a 20th-century relic—as if rock had become so old hat that it qualified as a fresh sound to 11-year-olds.

Bieber, on the other hand, was solidly in the lineage of classic puppy-love pushers in his early years, both in persona and in song structures; he often reminded me of his fellow Canadian Paul Anka, who sang “Diana” in 1957. But his hunger to grow up and get cool (more like his own mentor, Usher) has been evident for ages, particularly on his 2013 R&B compilation Journals, though the repentant mandate of Purpose requires it to back away from that set’s raunchier lyrics.

The music industry and the press tend to start demanding more “maturity” from teen idols fast, demonstrating how little respect they have for young female audiences and their tastes. All three of these albums take some of the prescribed steps: There’s more emphasis on the artists’ individual creative contributions as songwriters and musicians, their knowledgeable tastes, and the “edge” to the lyrical content. The gold standard is always Michael Jackson’s moonwalk out of child stardom to world conquest (ignoring all the fallout for pop’s ultimate Peter Pan). More recently, it’s Justin Timberlake, who miraculously remade himself from symbolic ’N Sync puppet to the grown-ass song-and-dance virtuoso who cleans up nice in a suit and tie.

All of which might seem only natural. People do, after all, grow older. But as the critic Margo Jefferson has written about Michael Jackson, “There is nothing natural about child stars. They are little archaeological sites, carrying layers of show-business history inside them … Child stars have to live out adult mythologies.” When it comes to baby-faced male pop singers, the myth is that if they want to be taken seriously they must claim control over their careers by asserting their masculinity—and for young teen female singers, by appearing more sexually available. Adulthood is equated with gender polarization.

Despite all the snooty smears from pop pundits and stand-up comics, the best joke ever told about teen idols and boy bands is still The Simpsons’ early-1990s invention of Non-Threatening Boys Magazine, through which Lisa follows the exploits of her celebrity darling, Corey. But it still trivialized too much the bonds between girls and their boy idols. First of all, as Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess, and Gloria Jacobs pointed out in their essay “Beatlemania” (written around the same time as that Simpsons episode), it’s not immature but sensible for girls to feel sexually threatened—by male coercion and a bright array of social stigmas and double standards, not to mention pregnancy, etc.

There’s more than just refuge in the androgyny of the boy bands, very much including the early Beatles, whose “long” hair read as queer to a crew-cut Kennedy-era America. They can make sexuality seem playful and fun instead of burdensome. They’re boys who are allies rather than opponents in some arbitrary game. Their supposed effeminacy allows fans to identify, and in turn absorb the musicians’ other attributes, including their potency and freedom. (Before you object to calling the Beatles a boy band, look at those early haircuts, matching outfits, and practiced stage moves, all products of manager Brian Epstein’s grooming. They patterned material after the popular American girl groups of the day and, exactly like 1D, says Paul McCartney this week in Billboard, wrote songs that were “completely direct and shameless to the fans: ‘Love Me Do’; ‘Please Please Me’; ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand.’ ” It was a template they had to set before they could break it, as of course they did.)

It is not only “softness” that marks teen idols as unmanly, but the very fact of being performers, gazed upon the way women traditionally are. Straight-girl fans of boy bands get to be the objectifiers instead of the objectified, and the pursuers instead of the pursued—don’t underestimate the force stored inside the word crush. Like a Beatle in 1964, a One Direction member wandering the city unguarded today risks being torn literally limb from limb by the mania of their modern Maenads. Perhaps Lisa’s periodical should have been called Non-Threatening Boys and Really Quite Threatening Girls Magazine.

Finally, teen-idol fandom is as much a mediator of intimate relationships among girls themselves as it is about the putative objects of their desire. Ehrenreich and company even claim that early-1960s Beatlemania was a foreshadowing of the feminist movement to come, “the first and most dramatic uprising of women’s sexual revolution.”

Obviously queer boys and girls (and straight boys who have the nerve, for that matter) have a lot to gain from public showcases of unconventional masculinity—witness Kate McKinnon on Saturday Night Live. The apparently desexualized gentleness of early-teen pop also makes it a place where sounds can traditionally be smuggled across racial borders, in sugar-coated form—a pattern from Pat Boone to the Beatles to Backstreet to Bieber.

Or go back even further to Rudy Vallee and Bing Crosby, as DePaul University’s Allison McCracken does in her great recent book on the “crooner” idols of the early recording age, Real Men Don’t Sing: “Every time a new, young, white singer with a soft voice attracts attention, the cycle of containment begins anew: Critical ridicule or dismissal, charges of effeminacy or emasculation, and calls for masculine rehabilitation, if possible … This nonsensical, punishing process has been so naturalized that it is largely unquestioned.”

When teen idols are pulled into the gears of the conventional de-feminizing, manning-up process, we should wonder why that’s the only option, and lament the magic of the teen no-man’s-land they are leaving behind. That’s part of what I hear in the mournful weariness of Bieber’s tone on Purpose. What is so automatically great about being a “real man” instead of a made-up boy? One element of MJ’s greatness is that his music refused to stop asking that question. By contrast, this month’s trio of new post-boy-band albums could be subtitled, “Today I Am a Man. Unfortunately.”

The hopeful sign is that the pop boys of this decade have never quite conformed to the old models, and neither have their fans. One Direction’s members are boisterously, intimately physical with one another in their shows and videos, unafraid of giving off homoerotic signals and welcoming of their gay fans—they don’t even seem much spooked by the obsessive “Larry Stylinson” conspiracy theory among some Directioners that two of the members are secret lovers, an epidemic of slash-fic taken literally (although they finally called foul when it led to fans harassing their girlfriends).

Besides, the center of pop gravity has shifted away from boys altogether—as if girls suddenly realized they could simply cut out the middleman and move on to directly idolizing each other. The stadium pandemonium for Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, and Beyoncé this decade has been every bit as deafening as for any males, and Swift cosigns that trend by parading her own “squad” of female friends in front of her fans, onstage and on Instagram.

As girls run 21st-century pop, they also rule social media, despite male trolls’ best efforts. This flips the script, too, perhaps leaving less of a role for the top-down machinations of would-be Brian Epsteins, Lou Pearlmans, and Simon Cowells of the future. If we can’t see many pop-music boy idols for current tweens, perhaps they’re looking somewhere else, for more creative interaction, even informed by a Rookie-style, more peer-to-peer feminism. (Could we call it fourth wave?)

Though both Bieber and 5SOS were YouTube discoveries, they were quickly assimilated into the corporate industry. But now, at least according to a Variety survey last year, the most influential personalities among young teens are the micro-stars of YouTube and Vine, comedians and chatterers such as Smosh and PewDiePie, all but invisible to adult eyes. One of the few male breakout pop idols of the past couple of years is Shawn Mendes, who cultivated his following in six-second bursts on Vine—and he stakes his identity more as a songwriter, a junior James Taylor type, than as a performer in the standard tween mode. This could be a Taylor Swift effect (see also her pal Ed Sheeran), but it may also be that on social media, it’s a reflex to expect that all users speaks for themselves.

In its conclusion, Real Men Don’t Sing suggests that American kids today are growing up in a more girl-positive and sexually fluid culture, pointing to the popularity of Glee’s out, gay, falsetto-singing characters earlier in the decade, as well as the rising visibility of trans youth, and gender non-conformists on pop-competition programs like The Voice. That rings true, though on the other hand machismo and anti-effeminacy still run rampant. But the mopey moods of younger male supremacists such as Drake and the Weeknd do make them seem queasy about some aspect of manhood they never manage to name.

For now, you have to look to Korea to find classic-model boy bands, as the K-pop training camps turn them out (and girl bands, too) like clockwork. In America, perhaps the sun really is going down on the era of doe-eyed, group-choreographed, peach-fuzzed pop guys, in favor of something fresh and unknown. But if all that emotional work ends up going untended, the girls surely will find them again. Just follow the screams.