Jim O’Rourke came slipping into my brainpan again a few months ago—well before I learned that this week he would be releasing the extraordinary Simple Songs, his first song-based solo album in 14 years.

A friend and I had ducked out of the frigid Toronto night into a little smudge of a bar to find a plucky post-college bunch from a town a few hours north doing a gig. The acoustic guitarist started finger-picking a lithe, sweetly familiar descending sequence. I strained to place it—Fleet Foxes? Early Bruce Cockburn? Maybe Mississippi John Hurt? Then the kid started breathing out lyrics over his scruffy lower lip, like a password into a keyhole: “Women of the world, take over, ’cause if you don’t, the world will come to an end.”

It was O’Rourke’s arrangement of the late eccentric Scottish artist Ivor Cutler’s “Women of the World,” from the 1999 album Eureka. “Wow,” I thought. “Kids that age still listen to Jim O’Rourke?” Then I reconsidered. “Well, of course they do.”

O’Rourke has passed from deep obscurity as an experimental composer and noisy, promiscuously collaborative free-form guitar improviser from early-1990s Chicago, to near-ubiquity as a player and producer in turn-of-the-millennium arty rock and “post-rock” circles (and contributor to films by Richard Linklater and Werner Herzog), to all but invisibility again after he decamped to Tokyo around 2006. But did his influence ever fully recede?

One argument would be that O’Rourke was part of a clutch of late-1990s artists who helped revive the troubled guitar innovator John Fahey’s rep in his final years with reissues and new collaborations. Fahey’s “American Primitive” folk-blues-and-beyond sound (honored on O’Rourke’s own 1997 instrumental album, Bad Timing) would become a key influence on a burgeoning national and global fingerstyle scene. Still, on that front, O’Rourke was but one of many movers.

A decade ago, you might have supposed his greatest impact would be as a studio guru: He had a decisive effect on Wilco’s evolution with 2002’s acclaimed Yankee Hotel Foxtrot and 2004’s A Ghost Is Born (for which he shared a Grammy)—not least by giving up his own regular drummer, Glenn Kotche, to the band. He also became a full-time member of Sonic Youth, co-producing and freeing up Kim Gordon from the bass, while producing and mixing for scads of other artists including Superchunk, Smog, Stereolab, Beth Orton, Joanna Newsom, and more. (He turned down the Rolling Stones.) But, in hindsight, few of those records were as big a deal as they seemed at the time.

Instead I would stump for the side of O’Rourke that few would have guessed existed until he put out a quick trio of solo records between 1999 and 2001—the recycled-pop artist, who made music that was actually catchy and lush, albeit with deceptive gaps and reversals, and morally ambiguous lyrics sung in a voice that could be either high and fragile or casual and crotchety. Eureka was as memorable for its then-unfashionably ornate, Burt Bacharach–venerating orchestral pop as it was for its blushing-pink cover painting of a man-baby rubbing his crotch with a stuffed bunny. It piqued the curiosity and pricked up the ears of a broader coterie, and was followed by the great Halfway to a Threeway EP and the twangier, scuzzier Insignificance, which Pitchfork would later include among the top 200 albums of the 2000s.

Those records came out at a moment when the pop world and the erstwhile underground still figured themselves to have irreconcilable differences, and at first people (me included) were unsure how to take O’Rourke’s turn to the pretty. Was he being sarcastic? The cover art said so, but the music seemed too beautiful and finely crafted, even as it drew upon uncool elements of the legacy of the ’60s and ’70s, from schmaltzy strings and cocktail piano to lite soul and slick California country-rock. Yes, the lyrics were dark and sardonic, but in retrospect not much more so than those of Todd Rundgren, Randy Newman, and Harry Nilsson or—more confoundingly to punk-nostalgic skeptics—Steely Dan.

A few of O’Rourke’s own associates were probing similar soft spots, notably Stereolab, the Sea and Cake, and, in another sense, Will Oldham, particularly on his Nashville Sound–alike Greatest Palace Music project. But only a few. This was long before the Yacht Rock Web-parody series that helped underwrite the cultural capital that the Doobie Brothers, Hall & Oates, Toto, and the Dan slowly began recovering in the late 2000s.

It was before Ariel Pink’s burst-bubblegum collages, Sufjan Stevens’ orchestral travelogues, LCD Soundsystem’s synthetic-sublime slouch into middle age, before chillwave or the meta-smooth horn sections of Destroyer’s Kaputt, before Future Islands was waitin’ on you, and before any critical manifestos in defense of schlock. And it is ancient history to PC Music, which represents a millennial mode of blenderizing commercial music that would have seemed highly suspect to most of O’Rourke’s own sellout-wary, late-Gen-X cohort.

After years of “ironic” punk covers of mainstream pop songs, O’Rourke was ahead of the pack in grasping that a pop “guilty pleasure” inevitably marks a spot where buried treasure waits to be unearthed, deeper down—that the most awkward and over-the-top feelings and gestures are where music is at its most nakedly human and, often, universal. (Not to mention its most binge-watchable on YouTube.)

In 2015, I think this is implicitly understood. As Chris DeVille has suggested on Stereogum, now the vein of ungainly, post-1960s–hangover music is being tapped all over the place, by the likes of Father John Misty (formerly of the Fahey-touched Fleet Foxes), Tobias Jesso Jr., Natalie Prass, Matthew E. White, Twin Shadow, and last year (less blatantly) Jenny Lewis—each sipping from the cups of Newman, Nilsson, Rundgren, Laura Nyro, Stevie Nicks, major O’Rourke influence Van Dyke Parks, and, in DeVille’s words, “Elton John when he could really send you to the moon.”

Misty’s self-parodying perv persona is especially reminiscent of Oldham’s and O’Rourke’s tuneful rear-guard assaults on rock masculinity. As for Jesso, he is even being promoted on the model of the late Stan Cornyn’s notorious, drolly self-deprecating early 1970s ads for Newman, Nyro, and Parks. (Each of those originals, by the way, was a more deft act of countercultural co-optation than the “Buy the World a Coke” confection that Mad Men’s finale attributed to Don Draper, who could never even get down with Volkswagen’s tongue-in-cheek “Lemon” campaign.)

Perhaps O’Rourke can’t be credited with inspiring any of that, but simply with anticipating it. His name is not dropped often by his apparent successors. A perpetually dissatisfied artist who’s seldom fond of repeating himself, he seemed to drop the smooth-rock project cold after Insignificance, busy with the better-paying Sonic Youth and studio gigs until his expatriation to Japan.

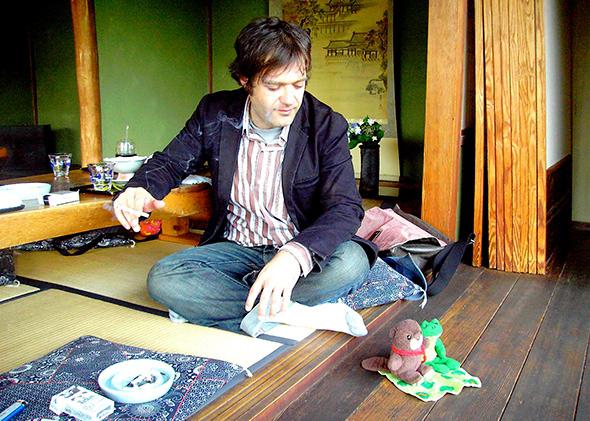

In Tokyo, the compulsively productive O’Rourke continued to do film scores, produce, improvise, and record. In 2009 he released the superb, multigenre instrumental The Visitor, a single 32-minute piece on which O’Rourke played every part—which involved, for example, studying trombone for six months to lay down one 10-second line. But almost nothing else he’s done has reached North American listeners, save the few inclined to scout out his noise albums with artists like Keiji Haino and Akira Sakata (e.g., And That’s the Story of Jazz) or his droning, 19-album Steamroom series.

How to account, then, for the belated appearance of Simple Songs, and how does O’Rourke’s take on pop come across in 2015? In part he has said that, after losing Kotche to Wilco, he could never find another drummer who could follow his exactingly off-kilter rhythmic sense. Then a few years ago he finally came across Yamamoto Tatsuhisa, who had the feel he needed. Adding bassist Sudo Toshiaki and pianist Eiko Ishibashi, O’Rourke spent years training the group almost like a “drill sergeant”—a clue to the degree of micro-detail engineered into these seeming pop bagatelles. One question the album raises is “how would a Japanese avant-jazz band have played 1970s AOR?”, an inquiry that could only come out of O’Rourke’s own specific cross-cultural experience.

That dislocated position, in space and in time, also factors, in the grooving opening track “Friends With Benefits,” into O’Rourke’s uncertainty about his own standing to sing (“It’s been quite a long, long time/ But not enough to find the line/ To get me goin’ once again”) and ours to listen (“But then what do I expect?/ You missed that boat a long time ago”). Yet in the song’s second section, which shifts into a wistful mode suggestive of the Canterbury Sound, the narrator explains he’s had trouble keeping in touch because he’s so busy with his obligations to the dead: “I hear from them every morning/ About all of their longing.” Spoken like a true exile, or a true 46-year-old—anyone in a “Half-Life Crisis,” as the title of another track puts it.

Overall Simple Songs is less mellow than Eureka and less boogie-woogie than Insignificance, constructed in equal measure around standup piano vamps and headstock-waggling guitar riffs, all punctuated by the glam sounds of Queen and particularly Sparks, those princes of artifice, with chimes and bells and cinematic swells.

In “Hotel Blue” an exquisite Leonard Cohen–esque Spanish-guitar ballad turns on a dime into a pounding power anthem featuring a Roger Daltrey–like scream. The closing “All Your Love” builds from a coffeehouse introvert’s meditation into a full-scale White Album–era Beatles jam à la “Dear Prudence.” Simple Songs has all the cantankerous energy of O’Rourke’s previous pop albums but also a freer hand, less to prove.

The gist seems to be less about conferring beauty upon degraded materials, the way the original trio of records did, and more about treating all musical forms as equal resources, as information to be sifted and put to use, like that Dutch design photo circulating this week of a hundred different kinds of food each cut into a perfect cube.

Though he is obsessive about procedures and processes, O’Rourke always has professed distaste for fetishizing any one element of music—he’s said he’s baffled by musicians who “love” their instruments, for example. They’re all simply tools to convey ideas. He relates to genres and sounds the same way. And in retrospect, that’s the most prescient aspect of O’Rourke’s career relative to 2015, when the fringes of pop music are full of people like him, the ones who might have advanced degrees in composition but split the academy for the trenches of popular culture.

I’m thinking of the sorts of figures you might hear at the New York City club Le Poisson Rouge, such as Nico Muhly, Dave Longstreth of Dirty Projectors, Flying Lotus, Ben Frost, Shara Worden, Owen Pallett, and others, who can talk about Luc Ferrari or Merzbow in one breath and Chic or Led Zeppelin in the next. Like O’Rourke, what they ask of any kind of music is not its pedigree or whether it’s cool but what else it can become; not even whether you like it, but how it alters a space. No songs are simple, unless all of them are, and they never remain the same.