After a four-year hiatus, the Portland, Oregon, group the Decemberists opened its new album in January with a characteristically theatrical move. In a curtain-raiser called “The Singer Addresses His Audience,” frontman Colin Meloy sings, “We know you built your life around us/ Would we change? We had to change, some.”

As Meloy explained in interviews, “That was my imagining the viewpoint of a singer in a band.” Which sounded a bit like O.J. Simpson imagining he “did it”—a rather timid leap for a songwriter known for epics about pirate ships and forest queens—until Meloy clarified he meant “a boy band.”

It seems supremely “indie” to assume that even if you’ve had a Billboard No. 1 album (on a major label, no less), conventional pop stars’ experiences are utterly alien to you. Yet perhaps Meloy was being coy: In the latter half of the 2000s, his band commanded a devoted audience given to costumes, fan art, and mass sing-alongs. The scene was a bit like a One Direction tour crossed with LARPing. So the reconstituted Decemberists may well have wondered if their fans were prepared to let them change, or if the less manic sounds and more mature concerns of their new album would draw a “WHAT ABOUT ZAYN?” kind of backlash.

Other music listeners might ask if bands of the Decemberists’ vintage can change enough to feel pertinent in 2015. A decade ago, music blogs, film and TV music supervisors, Pitchfork, and other new media outlets boosted “indie” to a rare visibility. Now, many of those acts are returning from long absences to quite an altered atmosphere. Early 2015 saw new albums by Sleater-Kinney and Belle & Sebastian, after 10 and five years respectively. Late March and early April have brought releases from Modest Mouse (after eight years), Death Cab for Cutie (four years), and Sufjan Stevens (five).

These never really were artists you could lump together easily, but for years they seemed to get by with “indie” or “indie rock” as an umbrella. Many people still use these terms, but what do they mean today?

The distribution shifts that enabled the indie boom of the 2000s have only multiplied, divided, and subdivided since then. Artists break out on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Vine, and Instagram, then market themselves there, directly to fans, no matter how famous they get. This hasn’t democratized music anywhere near the way indie partisans once predicted, but as overall music sales continue to deteriorate, it has blurred any clear distinctions between insiders and outsiders.

Consider the press conference last week for the revamped music-streaming app Tidal, which has set itself in opposition to the low royalty rates of other streaming services: There, a murderer’s row of rich and famous performers made a show of signing an ownership agreement as if it were the Declaration of Independence. Among the mostly pop, hip-hop, and R&B stars on hand, there were also indie rock–ish representatives Win Butler of Arcade Fire (pictured in Billboard’s report raising glasses with Jay Z and Beyoncé) and Jack White.

Photo by Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images for Roc Nation

Streaming royalty rates are a real issue, and maybe Tidal can be a partial remedy. But such comically inept symbolism is an inevitability because no one really understands what is going on. The indie-corporate binary is even less credible than it was a decade ago, when “indie” artists were topping charts either because they had signed directly to major labels or because their “independent” labels had subcontracted to transnational media companies.

Most of the new spate of “indie” comeback albums, then, come from artists now twice removed from their beginnings as non-corporate DIY units. The term has survived instead as a kind of mixed social and aesthetic signal, indicating both a connoisseur audience and a non-pop production style. On those levels “indie” carries a coded sense of aesthetic superiority—the legacy of “corporate rock still sucks”—that has always been a canard.

You can make great records if (and because) you don’t care about them sounding popular. And you can make great records if (and because) you care a whole hell of a lot about them sounding popular. Modest Mouse’s 1997 album The Lonesome Crowded West is a huge sentimental favorite of mine, but its rough-hewn sound is not inherently better or more meaningful than the highly produced ones of Michael Jackson or Blood, Sweat & Tears or the Beatles.

This clash flows out of and into the endless “authenticity” debate in music fandom and criticism. But in the time that most of the indie comeback artists have been away, a general consensus seems to have been struck. Musical hipsters right now are as likely to sneer at white indie guitar bands as an undifferentiated whole as at pop stars—which is also an unfair over-generalization, but may be the necessary corrective. Even the erstwhile indie bible Pitchfork now gives plenty of respectful attention to pop, dance, and R&B records it once would not have deigned to acknowledge.

In itself that doesn’t subtract from the relevance of indie artists. Few of them claim to be fighting any kind of battle against pop anymore—fans are almost always worse than artists on that count. But this decade has also seen a more widespread suspicion and critique of the workings of social privilege, and “indie” has a problem there—because its creators and listeners seem so disproportionately white, male, and upper-middle-class.

In late March, Pitchfork itself published a passionate critique called “The Unbearable Whiteness of Indie” by Sarah Sahim, which jumps off from a “blindingly white” film by Stuart Murdoch of Belle & Sebastian into problems of exclusion and appropriation on indie stages and in indie audiences. I have a lot of quibbles with the piece (chiefly her historically short-sighted dismissal of riot grrrl and other white feminist interventions as “feel-good”—go ask Russia’s Pussy Riot). But her central point is undeniable.

In the New Republic, Noah Berlatsky points out that the problem is actually circular—music made by non-white people is routinely defined out of “indie,” so that white people making neo-R&B or hybrid blues sounds are included but FKA Twigs and Valerie June are usually not. As Berlatsky writes, this is routine to how genres are formed. Very often, not much divided the sounds of blues and country, or R&B and rock. They were grouped by the racial origins of their performers, which both reflected institutional racism and for the industry served to organize market segments.

There are exceptions, and have been from Jimi Hendrix through Bad Brains through Bloc Party or TV on the Radio. (Not to mention artists of mixed race, Asian, or Hispanic backgrounds, among others.) Without them, the regime of separation would be too transparent and indie’s self-consciously liberal audience would be turned off as well. After the civil-rights era, even country music managed to rustle up a Charley Pride. The counter-examples enable the system to persist in mostly excluding minority participants or, through social expectation, discouraging their interest to begin with. (For evidence, watch Afro-Punk: The Movie.)

Sahim and Berlatsky each in their own ways call for widening indie’s tent, but I think it’s more realistic to pull it down. Because its insularity is not only racial and gendered—it is also the effect of sorting by class.

I made this argument when then–New Yorker pop critic Sasha Frere-Jones offered his own critique of indie whiteness in 2007, and it’s remained true: Indie is an acquired and self-sequestering taste, an implication not only built into the name but now its only functional meaning—the distinctive cultural “sophistication” and social status of its audience. One of the rival terms in the 1980s and 1990s that indie eventually eclipsed (along with alternative, underground, etc.) was college rock. It was more honest, which is no doubt why it was abandoned.

There are contradictions within the debate about indie and race, for example, that will never be neatly squared. For instance, the dangers of stylistic appropriation and the dangers of self-segregation can present a double bind. Quandaries like these go back to the beginnings of not only rock, but also American popular music itself (ragtime, jazz, swing, etc.). But when widening divides in wealth and privilege (themselves strengthened and perpetuated by the higher education system) are a central social crisis, the self-selecting “indie” identity is no help.

What do we call the music, then? Given the decline of mainstream rock as an adversary, who cares? Call it rock, electro, whatever it sounds like. Call it twee and precious, if that’s what you mean. In the always fraught struggle to listen to the music itself and not the social category, “indie” is just another blinder.

And abandoning indie just might make for better music, too.

Some of the bands in the “indie” comeback crowd would be robust no matter what you called them. Sleater-Kinney’s post–riot grrrl ferocious complexity has never made for a bad record and it hasn’t now. Modest Mouse has had its ups and downs, but leader Isaac Brock’s voice is his own, and he faces the relevance problem on the new Strangers to Ourselves by grappling metaphorically with the implications of the environmental crisis. It’s compelling, though maybe not 15-songs compelling. (He’s always needed an editor.)

Belle and Sebastian’s effort at making a quasi-disco record with Girls in Peacetime Want to Dance, however, would be strengthened if the walls of their cloister could fall—if, instead of “disco enough for indie,” they had the ambition to compete vigorously with disco itself and its current dance-floor heirs. This studied sense of distance is why indie “appropriation” is usually less convincing than the pop variety.

Death Cab for Cutie’s Kintsugi sounds much like any Death Cab album—but time has not been kind to their placidly competent guitar-rock or to Ben Gibbard’s lyrics, which I don’t recall being so riddled with romantic, gender-stereotypical clichés. (Which may be to say that I was once less sensitive to those flaws than I am now.) Even if you try to ignore the fact that some of its passive-aggressive bull is directed at Gibbard’s ex, Zooey Deschanel, it irks. I switched it off after the tune with the chorus, “My love, why do you run? For my hands, they hold no gun.” Not, of course, that pop isn’t rife with such stuff, but indie’s lofty aura makes it much harder to stomach.

Likewise I am a bit skeptical that without “indie,” the Decemberists could even exist. If there were then still a call for a post-modern folk-rock Gilbert and Sullivan, it would have to have more of the courage of its strangeness. The band’s hiatus has done it some good, and the songwriting is more grounded on this year’s What a Terrible World, What a Beautiful World. But I still find Meloy’s unrelenting streams of conceits wearying, like a prog concept album from 1975 without even the gonzo musicianship to liven up the occasion.

More than any other band, they bring me back to the self-regarding turn that America made in the 2000s—the post-9/11 world-wariness and self-soothing. It would be too much to say that’s what made it an ideal period for “indie.” But when I listen to the Decemberists, I’m tempted.

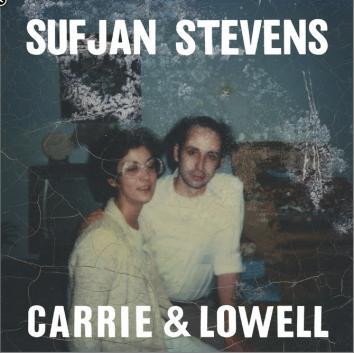

Album art for Carrie & Lowell

Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie & Lowell, on the other hand, may be the finest album of his career—and along with its deeply personal narrative of family, fear, and faith, it is partly because it’s free of the attention-grabbing cleverness of much of his 2000s work. You can call it a folk record, without scare quotes or the indie modifier. It is solitary but not at all withholding, as Ann Powers beautifully illustrates in her NPR essay centered around it (which, speaking of anti-segregation, parallels it to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly).

Finally, there’s one last thing I would hope abandoning “indie” might nudge ahead: a renewed search for non-corporate models of music making. Ones that speak to today’s questions and crises, without all the baggage and socially compromised affiliations that have accrued over the 40 years since the dawn of punk. The new model might be a crowd-sourced streaming service of some kind, or it might be an outgrowth of the SoundCloud pages some people maintain not as calling cards but as ends in themselves. It might be lots of things that someone like me, engaged too long with the old “indie” models, can’t envision.

It is true, after all, that hopes for digital democratization have degenerated and instead tend to reinforce the hegemony of the musical “1 percent”—the people on that Tidal stage and, more importantly, the corporations that sponsor them. Pro-pop populism can never be the complete answer. There are experiments to be made in screaming unpalatable truths, in sustainability in all its senses, and in the simple joy of making music with others on more localized, intimate grounds.

“Indie” can’t do it anymore. But musicians and audiences of all stripes could. Can we change? We have to change some.