6 Man

What’s so Canadian about Drake? Our Toronto-based music critic offers his own views from the 6.

Photo illustration by Slate; Photo by Bruce Bennett / Getty Images; iStock

As divisive within hip-hop as Kanye West is outside it, the rapper-singer Drake surprise-released a compelling new album/mixtape/alleged-ploy-to-fulfull-his-contractual-obligations this month. Surprisingly, for a putative “mixtape,” If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late reverse-BASE-jumped to the steel broadcasting antenna at the tippy-top of the album charts, with Drake taking over a record 40 percent of Billboard’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart. What’s no surprise at all is that the new tracks find Aubrey Drake Graham continuing to barnstorm for the post of chief cultural ambassador for Toronto, his hometown and mine.

The former co-star of prime-time teen soap Degrassi, in which he played the northland’s wheelchair-rocking Jimmy, Drake has lately stumped hard for the metropolis he’s insisted on rebranding “the 6”—in honor of its 416 and 647 area codes, as well as the current megacity’s 1998 amalgamation out of six separate municipalities. (Past Toronto rappers came up with “the T-dot,” while older locals referred to “TO” or “Hogtown.”) Drake presses the matter on If You’re Reading This, with songs such as “6 God,” “6 Man,” and “You & the 6,” not to mention the infectious hook on “Know Yourself,” “I was runnin’ through the 6 with my WOEs.” The projected title of his next planned 2015 release? Views From the 6.

But Drake is not only the first Torontonian to summit the rap game, he’s the first from our whole northern nation. So the Toronto-centrism of Drake’s output obscures a larger issue: What is Canadian about Drake, and how does that affect how listeners feel about him?

I’d argue his nationality is actually one of the reasons American observers often find Drake’s persona hard to decipher, but all too tempting to read: He’s playing with a maple-leaf-embossed rulebook that doesn’t entirely translate south of the border. Where an American rapper might tackle a topic, Drake body-checks it; where another would slam-dunk, he dekes.

In the interest of cross-cultural understanding, then, permit me to suggest the six most Canadian things about Drake, or perhaps the six Drakiest things about Canada.

1. Official Multiculturalism

The press’ standard shorthand for Drizzy is “biracial, half-Jewish, former-child-actor Canadian rapper,” and that’s enough to mark his difference from the standard U.S. hip-hop template of rising from the streets. But in Canada that’s not such an oddball rap sheet. The makeup of minority communities here doesn’t share the same history nor follow the demographic patterns of U.S. cities.

The diasporic black community in Toronto, for example, is heavily Caribbean, from diverse islands and outposts, and hip-hop in Canada has long been as much inflected by reggae and dancehall (not to mention South Asian and First Nations sensibilities) as by black American styles. In that context it wasn’t much phonier for white rapper Snow to borrow his neighbors’ Jamaican patois in the oft-clowned-on “Informer” (back when Drake was 6) than it was for Eminem to swipe his rap-battle partners’ patter from either side of 8 Mile Road.

Nor is it so strange for Aubrey Graham to sound off in island slang on occasion, as he does in the arty promo film for If You’re Reading This. As Toronto music critic Rawiya Kameir tweeted, “lmaooooooooo at everyone who said drake has a ‘new accent’ obviously you’ve never met a toronto roadman before.” (Toronto ex-Mayor Rob Ford doing the same inebriated in a late-night patty shop is a dicier matter.)

Every Canadian kid learns in Social Studies that Canada’s federal policy on immigration is in contrast to the American “melting pot” model of assimilation, instead aiming at a “cultural mosaic” in which newcomers retain their heritage—keeping the hyphen active and hot in terms such as African-Canadian, Italian-Canadian, Jamaican-Canadian, etc.

Official multiculturalism has proved to be no panacea for racism. It’s not as if Canadian cities don’t have ethnically disenfranchised ghettos. But they tend to be more mutable and unstable, less entrenched over decades. So it’s not so contradictory as it might sound for Drake to claim a mobile stake in the more hazardous corners of gang-afflicted Scarborough as well as in affluent Forest Hills—where, for all the flak he drew over “Started From the Bottom,” he and his chronically ill, divorced Jewish mother lived in lower-middle-class digs till he started bringing in TV paychecks.

Meanwhile Aubrey spent occasional summers in Memphis with his African-American dad, who like his more famous siblings is a former high-level studio musician, but fell on rougher times, including jail stints. On If You’re Reading This’ moving song for his mom, “You & the 6,” Drake implores her to join him in forgiving the old man. What I want to hear someday is the yarn of how Dennis Graham and Sandi Sher hooked up in the first place.

Drake arrived on the scene at a point when Kanye, in particular, already had opened up space for more middle-class, introspective black voices in hip-hop. That’s Drake’s kind of hustle. But dismissing him as a silver-spoon kid via remarks like “Gangsters don’t have Bar Mitzvahs” is kneejerk. Is Drake the one over-romanticizing poverty and struggle, or has he simply been yielding to the pressure of constant U.S.-minted cred checks?

2. Broken Social Scenesterism

Claus Andersen / Getty Images

For decades the mantra in Canada (where the population is one-tenth that of the U.S. across an even larger area) was that if you wanted a career in the arts you would have to leave. For a while in the 1970s and after, a wave of cultural nationalism brought generous government funding for the arts, but that’s gradually dried up under Canada’s ongoing version of Reaganomics.

Still, the 21st century has seen independent Canadian artists, enabled by the access online culture allows, seeking ways to reach out without severing their roots. Drake signaled his own approach on his breakthrough 2009 mixtape So Far Gone when he declared he was “hardly home but always reppin’.”

His strategy isn’t unlike that of Toronto indie bands such as Broken Social Scene (including adjunct members like Feist) and Montreal’s Arcade Fire and Godspeed You! Black Emperor, whose collectivist ethos led them to bring international success back home in the form of studios, labels, mentorship, venues, and festivals.

Callbacks to hood and hometown are standing rap requisites, but a border is a hard barrier, so Drake’s homebound commitments aren’t merely rhetorical, nor confined to propping up the morale of the Toronto Raptors (as he does courtside so many nights). The prime mover of his throbbing after-dark sound has been homegrown collaborator Noah “40” Shebib—incidentally another ex-child-actor and the son of Donald Shebib, the writer-director of the landmark 1970s Canadian independent feature Goin’ Down the Road. 40 and Drake have stuck by each other, lately joined (as on this record) by other GTA-based producers such as Boi-1da and WondaGurl.

Drake’s own OVO Sound label has been signing and grooming Toronto rap and R&B talents to follow earlier protégé The Weeknd into the limelight. He shrugged it off when his annual OVO Fest, the largest hip-hop event Toronto has ever seen, caught heat for receiving a $300,000 government grant—hey, that’s just how the left hand washes the right, here in the sloppily socialist north.

The flip side of this one-for-all mindset, though, is the risk of provincial insularity. Drake is happy to swap bars with all of rap’s rich and famous, but at a more intimate level he’s stuck with his paranoid “No New Friends” policy. Two years back you could hear it on “Started From the Bottom” (“No new niggas, nigga, we don’t feel that/ Fuck a fake friend, where your real friends at?”) and you can still hear it, more pointedly and I think more sadly Canuckishly, on new track “6 God”: “No one really likes us except for us.”

3. Media Criticism

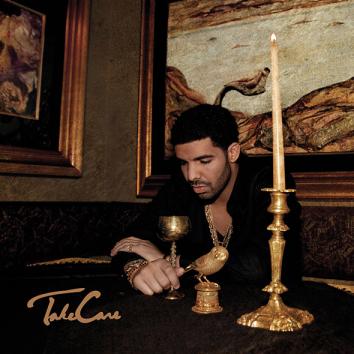

How does Drake love and hate communications technology? I’ll let the venture capitalists at Genius total up the ways, but ever since the drunk-dialing rhapsody “Marvin’s Room” on Take Care, he’s claimed the laurels of the 21st-century bard of telephony. While he’s hardly the only millennial MC to obsess over his smartphone, I can’t think of another whose digitally mediated desires have him so thoroughly wrapped around his own fingers.

Take the new track “Star67” (named for the old touchtone code for call-blocking), on which Drake meticulously details his practices for screening calls. No, Drake isn’t letting it go to voicemail when Yeezy or Weezy rings up, but according to the new album, when he gets a “text from a centerfold,” what does he do? “I ain’t reply—let ’em know I read it though.” Or take “Energy,” on which he disses dames for badgering him for his Wi-Fi password (“so they can talk about they [Facebook] timeline/ And show me pictures of they friends/ Just to tell me they ain’t really friends”) and dismisses somebody by saying he’s “bout to call your ass an Uber.”

Then again, he plays hard to get with tech, too, again on “Energy,” sneering, “Fuck goin’ online, that ain’t part of my day.”

And why? Because he’s Canadian.

Thanks to dispersed populations who endure long winters indoors, yearning to reach out and touch someone, Canada has been a leader in telecommunications—from the days of Alexander Graham Bell, through the radio-collage compositions of Glenn Gould, to the early adoption of cable TV, to the reign of the BlackBerry.

Perhaps as a result, many of the country’s leading thinkers have been media critics, such as Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan, and (U.S.-born Vancouverite) William Gibson, the author who coined the term cyberspace.

This multimedia fluidity is also why, as Grantland noted last year, it’s hopeless to try to out-meme Drake, no matter how hard mockers try: “You can’t invent Draking. Drake’s been Draking for 27 years.” It’s just like how Americans never realize they can’t come up with a Canadian-dullness joke that Canadians didn’t think of first.

4. Sexual Agoraphobia

Drake’s teledildonic preoccupations plug neatly into another distinctly Canadian cultural trope: the weird-sex problem. It’s an onanistic nation (again, all those chilly shut-in days) colonially hemmed in by British repression on one side and American post-puritan sexual commodification on the other. These pressures end up bursting through novel channels, some liberating, some revolting.

This is a country in which one of the landmark literary novels is about a woman who becomes erotically fixated on a bear. It is the home of David Cronenberg’s exploding orifices and Atom Egoyan’s creepy, voyeuristic cinema. One of our more famous contemporary short stories, by Toronto writer Barbara Gowdy, is about an enthusiastic young female necrophiliac, titled “We So Seldom Look On Love.” (Drake’s hometown paper once asked, “Why is Canadian sex so creepy?”) Where America’s representations of perversity often seem to be about being bought or buying, used or using, Canada’s are, as Toronto’s great queer new wave band Rough Trade once put it, “all touch and no contact”—distance, alienation, and fetishistic substitution.

And that’s Drake on Take Care’s “Doing It Wrong,” mumbling, “Touch if you need to, but I can’t stay to hold you, that’s the wrong thing to do.” He alternates between gallantry and gaucheness, romanticism and narcissism, solicitude and selfishness, all within one series of sexts. On the same album’s “Lord Knows,” he demurs about “a couple of porn stars that I’m ashamed to mention.”

The same guy who’s parodied as going to the farmers market and asking a bruised apple, “Who did this to you?” can be heard, on the new album, crowing that he’s so sexually knowing, “I got strippers in my life but they virgins to me.” On that same song (“Energy” again), he whines about everyone “tryna drain me of this energy,” and comes off like General Ripper in Dr. Strangelove ranting about the communist plot to infiltrate Americans’ “precious bodily fluids.”

People like to lampoon Drake as rap’s Morrissey, but his slurry of solicitude and sexism makes him less like an O.G. than one of Canada’s O.S.G.s: original sensitive guys, such as Leonard Cohen, Gordon Lightfoot, and Neil Young, who blame their gloomy troubles on the same temptresses they beseech to be their saviors. They’re gynophobes disguised as ladies’ men. If “A Man Needs a Maid” weren’t a title on Young’s mellow-gold 1972 classic Harvest, it could easily have been ripped from a Drizzy mixtape.

5. Passive-Aggressive Self-Pity

But Drake’s roundabout, sexually undermining come-ons are only a subroutine of his general modus operandi as the ultimate “humblebraggart,” as Jody Rosen dubbed him. He is the type of dude who wants to have his pound cake, his luxury “safe house,” his “two mortgages ($30 million in total),” his strippers, and his chart supremacy and despise them all, too. It’s probably Drake’s most consistent ploy, the poor-little-rich-man stance, and I can’t blame people for hating it. Because I do, too.

Listen to him on the hook for If You’re Reading This’ opener: “Oh my god, oh my god, if I die, I’m a legend”—bemoaning that he is trapped in his greatness now, and how will he ever live with that? Similarly, Drake might claim that those “WOEs” he runs around with are his crew, who are all “working on excellence,” but this is a guy who’s slung a pun or two, and he’s well aware we’ll hear it as talking about his troubles, too.

A tortured relationship to your own success isn’t a great look, but Drake is helping make it an epidemic trope in 21st-century hip-hop—it puts me unpleasantly in mind of The Wall-era Pink Floyd, when arena-rock stars first pivoted from basking in their glory to bemoaning it. It’s the decadence that follows a genre’s imperial phase.

But I do feel Drake here, because being a famous Canadian is to come pre-condemned. This country is deeply infested with “tall poppy syndrome,” an urge to take down anyone who rises above the crop. Drake is well-acquainted with this part of the national character: On last year’s tossed-off hit “0 to 100/The Catch-Up,” he recounts a friend saying, “You know that if you wasn’t you, you would be dissin’ you, dawg” and he admits it’s true. In those circumstances you begin anticipating and defending against the envy by taking yourself down first. It might begin with humor but it can easily decline into self-pity.

Drake is equal parts full of himself and the very picture of the Joni Mitchell summation of the Canadian character, “You brush against a stranger, and you both apologize.” Canadians say “sorry” a thousand times a day, but we’re not genuinely sorry—we’re trying to exempt ourselves from any possible blame. The politeness we’re praised for is often veiled hostility.

So when I dislike Drake for his self-admitted passive aggression and hangdog humblebrags, as I especially did on his first few records, it’s surely partly because he’s reminding me of myself. Viscerally I find myself preferring the more untrammelled aggression of much of If You’re Reading This, but I actually think it makes him a less interesting character. What gives him dimension and humanity is his highly Canadian authentic inauthenticity, his outsider-insider stance, one step removed yet invested all the way. I agree with the Atlantic’s Spencer Kornhaber that “he’s at his best when he’s going hard at being soft.”

Anytime that makes me squirm, it may be less Drake’s Canadian problem than my own.

But then I think again about the title of his new whatchamacallit: If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late, written apparently in his own hand. Whether or not he’s trolling his record label, it also calls to mind the wording of a suicide note. It’s another one of his threats to hold his breath till he turns blue unless he gets his way, as if he hasn’t already had it his way as much as Frank Sinatra going to Burger King. Damn it, Aubrey, you’ve still got it, you hoser.

6. Orthography

All right, then, Drake, let’s make a deal: Would you promise to revert to Canadian spellings, as you initially seemed to when you released Nothing Was the Same’s tough-fronting “Worst Behaviour,” or when you tweeted demanding YOLO royalty “cheques” from Walgreens?

If so, I’ll really, really consider calling Toronto “the 6,” at least once in a while.