There’s an uncanny symmetry of form to the way that Björk’s new album, Vulnicura, came into the world last week. Superficially it resembles recent releases by Beyoncé, D’Angelo, and others, as a so-called surprise album drop—this time around, not as a marketing strategy but as a tactic to counter an Internet leak. (It was meant to come out in March.) But what’s been “dropped” in this case is more like emotional ordnance, a neutron blast that fissures the self while the surrounding landscape stands undisturbed and the march of days carries rudely on.

The recording’s sudden appearance mirrors its subject: Vulnicura is an anatomy of how heartbreak—no matter how predictable or anticipated—lands as a singularity, a before-and-after point. Once there was warm certainty, now cold distance; once there was we, now only I; once there was you but now you are him. It is an album about a life exploding.

The intimate detonation here, as fans and art-world gossips will know, is the Icelandic singer’s split with visual artist Matthew Barney, her romantic and sometimes creative partner of more than a decade, and the father of her 12-year-old daughter, Isadora. Vulnicura, a title hybridized from the classical Greek terms for wound and cure, consists of nine songs, most of them long and slow. In the lyric booklet, three are dated some months before and three some months after the calamity, and then there are three undated pieces listeners might take as time-stamped roughly now, post facto, when each new morning is no longer strapped to the moment of rupture by measured lengths of viscera.

It’s a pattern everyone who’s been through major heartbreak will recognize. The fact that time does heal is merciful but also reducing. It renders our past losses unjustly banal. Perhaps to counteract that effect, the bulk of the album unspools in media res, as if transcribed straight from her interior monologue. Her Icelandic accent is differently conspicuous than on previous records, the exotic contour of a vowel or trill of an r making each lyric feel yet more private and personal. In the opening track, “Stonemilker,” Björk sings “moments of clarity [clah-rrri-tee] are so rare / I better document this.” One of the qualities that sets Vulnicura apart from almost any other “breakup album” is its cinéma vérité ambience.

Björk’s own comparison, in her intense recent Pitchfork interview, was to Ingmar Bergman and Liv Ullman’s Scenes From a Marriage, a four-hour domestic drama that often makes you want to hide your eyes as if you were watching Leatherface chain-sawing a bare torso. The hour-long Vulnicura can be similarly uncomfortable, not just due to the flayed emotions but because so much of the music is ravishingly ugly. Many of the electronic sounds are generated by her co-producer, the young Venezuelan-born adept Arca, who’s worked with Kanye West and FKA Twigs. Björk has engaged him as her one consistent interlocutor here, in a duo in which the sounds he makes stand in for the absent romantic partner.

As the crisis deepens from song to song, lucid violas and cellos increasingly surge out of sync with craggy beats and lurching synth lines, like lovers arguing past each other, like thoughts coming unsprung in gut spasms of remembrance. There are absorbent tonal clusters and then disorienting gaps. Disputing with her lover and herself, Björk—or multiple Björks in overdub—often sings each melodic line as a monadic unit that may or may not relate to the previous or the next: “one. feeling. at a. time,” as she dissects it in the second track, “Lionsong.” You can feel the performative stamina these songs demand, deep in your own chest.

The way the disparate parts of the music don’t quite interlock reminds me of the way Anne Carson frames desire through classical Greek poetry in her exquisite study Eros the Bittersweet: “The boundaries of time and glance and I love you are only aftershocks of the main, inevitable boundary that creates Eros: the boundary of flesh and self between you and me. And it is only, suddenly, at the moment when I would dissolve that boundary, I realize I never can.” The clutter, shimmer, and skew of Vulnicura seem to reflect the rare state in which those boundaries can dissolve: when the object of desire is gone. All the negotiation of edges that comprises a relationship (vividly, if one-sidedly, depicted in the first few pre-breakup songs) drops away, and there is a void where that friction used to be—an excess running off into an undifferentiated “Black Lake,” as the album’s bleak 10-minute centerpiece is titled.

The task from there is to recover an outline of the self not defined by its proximity to the beloved. As Carson writes, “When I desire you a part of me is gone; my want of you partakes of me.” One compensation to being left alone is to make fresh acquaintance with that missing piece.

This is not pop and it is not soothing chamber music. But its candidness makes it magnetic and graspable in a way Björk’s records haven’t been since 2001’s Vespertine. Albums such as Medulla and Biophilia were impressive conceptual and technical coups, but felt more like gallery installations than music that urgently wanted to inhabit its listeners’ lives. Those projects smacked of the art world, and perhaps it’s not immaterial that they overlapped with her partnership with art star Barney. Now, in extremis, it is as if she is appealing for succor to a more reliable relationship, the one she’s shared for decades with her audience.

NPR critic Ann Powers accurately labels Vulnicura “an inquiry into melodrama,” that long-standing form of “women’s culture,” as feminist cultural theorist Lauren Berlant says in her book The Female Complaint. Melodrama calls a presumed community into existence, an “intimate public” in Berlant’s terms, of women who share “the bitter vigilance of the intimately disappointed” (as well, traditionally, as those who are excluded from domestic intimacy due to queer sexuality). Berlant writes, “Everyone knows what the female complaint is: that love is the gift that keeps on taking,” and on this album it has taken nearly everything.

Melodrama makes the implicit bargain that if the artist offers up her agony, her public will reward her with its tears, of identification, of sympathy, perhaps even of solidarity. Yet the staging ground of conventional melodrama is the lace-curtained middle-class home under peril. How does it translate for a famous, affluent, techno-pagan bohemian internationalist on the threshold of 50?

While Vulnicura may be like a 21st-century Blue, “boho-genius-superstarwoman” was an identity Joni Mitchell had to invent and achieve. Björk Guðmundsdóttir was effectively born that way. She was raised partly on a commune, made her first pop album at 12, and was involved in punk rock and radical art collectives in her teens, in an island nation that within her own lifetime leapfrogged within from a mythopoeic sea-village culture to postmodern globalism.

In Björk’s past work, the domestic sphere has seldom threatened to take precedence over realms oceanic, subatomic, microbial, or interstellar, much less those cross-cultural, cyberspatial, political, collaborative, and hypersonic. So it’s startling to hear her cry out, like Bette Davis or Jane Wyman in a midcentury weepie, “Did I love you too much?” or level a grievance against Barney such as “Family was always our sacred, mutual mission, which you abandoned.” To hear Björk in this condition is as dismaying and disarming as a first reading of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking—the same sense of the urbane sophisticate stripped down and laid low by grief, albeit all the more articulate in her strickenness.

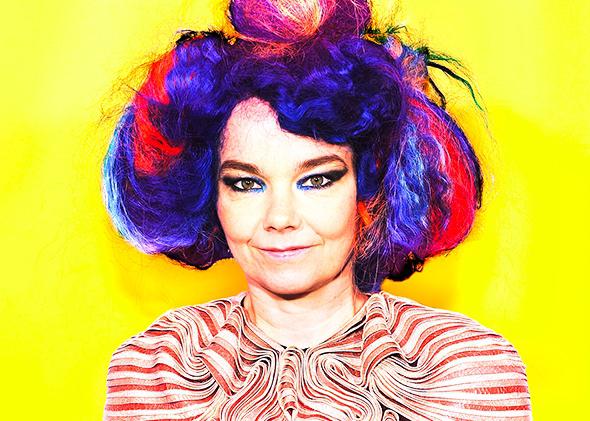

But being a generation younger than Didion and a European feminist artist who is in tune with her sexuality even in her distress, Björk locates her melodrama not in the home but in the body. The closer a song lies to the narrative epicenter, the loss itself, the more physical its vocabulary: The final “before” song is “History of Touches,” about the last time the partners have sex; the first “after” song, “Black Lake,” starts with the declaration “Our love was my womb,” but adds that now “I am one wound, my pulsating body, suffering being.” Together these lines evoke the album’s cover image of Björk clad in black, bristling with febrile emanations, with a vulvalike cavity opening raw across her chest.

With this album Björk is crossbreeding melodrama with the messy self-experimentation of 1960s and 1970s feminist body art by the likes of Yoko Ono and Carolee Schneemann (though since this is Björk, one must also think of science, fashion, clubbing, community choirs, and handicrafts). On “Mouth Mantra,” she fondly addresses her own jaw, mouth, and throat, “this tunnel [that] has enabled thousands of sounds,” referring at once to the silencing power of her grief and her surgery in 2012 for vocal cord polyps. “I thank this trunk, noise pipe / I have followed a path that took sacrifices / Now I sacrifice this scar.” (I also wonder if bringing these two highly gendered genres into play is a subliminal way of talking back to Matthew Barney, whose own most famous work, the Cremaster video cycle, is an exhaustive study of tropes of masculinity.)

Björk’s callbacks to historic feminine-culture modes on Vulnicura highlight, and perhaps protest, the invisible emotional work that continues to fall to women even in the most supposedly enlightened and artistic milieus and partnerships. It’s what Berlant calls “the sentimental bargain of femininity”: the labors of family and romance, emotion and Eros, tend to be conflated and confused into “ongoing circuits of attachments that can at the same time look like and feel like a zero.”

But Björk is a stubborn optimist and futurist far more than she is a critic. This is the woman, after all, who’s on record as threatening, “If you complain once more, you’ll meet an army of me.” For all her righteous, unanswerable anger that there is no “place where I can pay respects for the death of my family” (sung over thumps and scraping knife blades, one of the album’s most punishing moments), before too long she is asserting that “a swarm of sound around our heads” can “make us part of this universe of solutions.”

This is the unexpected gift that is Vulnicura, that it both breaks with the hermeticism of her more conceptual projects and transcends its own melodrama, coming through its vale of tears reawakened, damp and shiny. “When we’re broken we are whole,” she concludes, “and when we’re whole we’re broken.” Can she get an amen? It’s painful to feel like we witness Björk undergoing the ordeal that Vulnicura memorializes and ritualizes, but that ordeal has pried open an unforeseen range of expression in her that may restore her bond with listeners who’d drifted—and endear her to new intimate publics. In the Björkian calculus of cosmic balance, this may not recompense all her sorrows, but it does amount to much more than zero.