It was a decade ago that I became aware of Los Angeles songwriter Jenny Lewis, first lured in by “Portions for Foxes” by Rilo Kiley, the indie rock band she fronted with her then-partner Blake Sennett. It’s a guitar-tangled, messy-bedroom story, with Lewis’ slightly out-of-breath vocals banking around the corners of a lust triangle as if drawn by an inevitability:

And the talking leads to touching

And the touching leads to sex

And then there is no mystery left.

And it’s bad news, baby, I’m bad news

I’m just bad news bad news bad news.

It showed off many of Lewis’ strengths as a songwriter: an almost gossipy relish in people making bad decisions, especially sexually; a killer instinct for the consequential moment; and a fearlessness about calling herself out, but without slighting her own significance, no matter how screwed up she may feel. Her voice clinched it, an actor’s instrument by turns beguiling and standoffish, staking it all on the sheer energy of narrative. Ever since, listening to Lewis, I notice how she sifts the details of her stories and then gathers them up to verbal and musical peaks—the bits that demand repeat play, the lines you’ll sing back to yourself in the shower, the parts in italics.

There are many such heights on Lewis’ new solo album, The Voyager. On the second track, “She’s Not Me,” for instance, there’s the point when a Stevie Nicks groove of a gripe about an ex’s new lover gives way to another truth in a suddenly tougher Chrissie Hynde lip-curl: “Remember the night I destroyed it all/ when I told you I cheated/ and you punched through the drywall/ I took you for granted/ When you were all that I needed,” each stressed phrase thumped home with a double-strike of symphonic strings.

Then there’s the first single, “Just One of the Guys,” which has brought Lewis to new audiences thanks to a video featuring her Hollywood friends Anne Hathaway, Kristen Stewart, and Brie Larson done up as slimy dudes in ’staches and track suits. At its pivot point, the track’s girl-group wall of sound (produced by Beck) falls away and Lewis calls herself “just another lady without a baby.” Many listeners have taken it as confessing fertility angst, but it’s really about why someone like her is seen (including by herself) differently than any male musician her age would be. Notice that the song opens by complaining about her guy friends dating ever-younger women. The sharpest sting, though, comes at the end, when Lewis drawls, “I’m not gonna break for you, I’m not gonna pray for you, I’m not gonna pay for you/ That’s not what ladies do”—a rebuttal to decades of rock-guy songs like Bob Dylan’s “Just Like a Woman,” with its patronizing guff about how the object of his semi-attentions “breaks just like a little girl.”

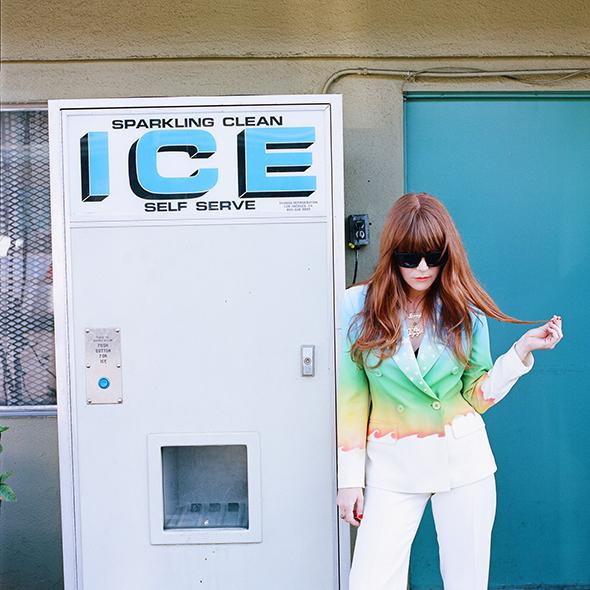

There aren’t a lot of songwriters who reliably locate these sorts of melodic, dynamic and emotional pinnacles. But it doesn’t happen in every song, and on first exposure, Lewis’ vocals and her style can seem merely conventionally attractive. That’s convenient for anyone who’d prefer to dismiss a pretty California redhead who carries casually her book and street smarts, vocal facility, dress sense, and sass. In navigating the passage between indie cult status and more mainstream fame, she runs up against people for whom the very obviousness of her appeal is a reason to resist it.

Rilo Kiley always walked a line between DIY authenticity, with its ties to Nebraska’s Saddle Creek label, and the fact that it was a thoroughly Californian outfit led by two former child actors (Lewis was a tween star in films like Troop Beverly Hills 25 years ago). But the band’s evolution to an ever more Technicolor, wide-screen sound was purposeful. As Robert Christgau pinpointed it in 2004, in “a subculture where obscurantism is expected, that [their songs] have meanings at all suggests why they sound the way they do. It’s a formal commitment. Rilo Kiley want to be understood.”

With Lewis’ and Sennett’s romance long ended, the wheels finally came off Rilo Kiley somewhere around 2010. The Voyager emerges after a period of mourning for that loss, as well as the death of her long-absent musician father and other personal troubles. The result is her first solo album that doesn’t sound like a side project—not exactly a coming-of-age, because I wouldn’t have called her immature a decade ago, but it’s definitely a kind of reckoning. Lewis is living with fellow songwriter Johnathan Rice (with whom she made 2010’s I’m Having Fun Now as Jenny and Johnny) and sizing up the implications of staying the course, both as a romantic partner and as a solo artist, including the pleasures and accumulated damages of the musician’s lifestyle.

Musically it is her most Californian album yet. Produced mainly in the studio of self-styled auteur Ryan Adams, it owes a lot more to Linda Ronstadt, Fleetwood Mac, Brian Wilson, the Bangles, and even Sheryl Crow than to anything indie, or to the Appalachian drag Lewis affected on her first solo record, Rabbit Fur Coat (2006). It’s also supremely Californian in its sexual and psychoactive-substance mores, fuzzy psychoanalysis, hotel hedonism, flirtations with polyamory, and general body consciousness. She deals in contradictions, but less often in irony.

It’s a feminist album in many ways, but more in the vein of interpersonal dramas of recrimination and regret than the broader social confrontation you might expect from a like-minded songwriter in Brooklyn. Lewis is driving away in designer sandals, not stomping out in army boots, with a sticker that reads “The journey, not the destination,” on her rear bumper. Hell, this is an album that comes complete with its own wine pairing. You either raise a glass to her brazenness or pour the thing down the sink.

Everyone’s aware of the East Coast–West Coast split in hip-hop. The subject doesn’t come up so much around rock. But I can’t be alone in carrying an anti–West Coast bias, and particularly an anti-SoCal one. Maybe it traces to growing up in the hair-metal era, when all the silliest spandex-wrapped groups in music videos stalked the Sunset Strip. Or maybe it’s just an instilled prejudice against Los Angeles itself, which I never visited before I was an adult and pictured as a car-clogged hellscape of shallow disconnection and cash-powered culture, because New York propagandists like Woody Allen told me so.

Today, having spent some time in L.A., I think differently: Its art and literary scenes seem more ornery and independent than on the East Coast, where there’s always an underlying pull to suck up to established cultural power, and musically L.A.’s diversity is overwhelming. I’m still a bit startled whenever I find out a friend once paid sincere attention to, say, the Red Hot Chili Peppers or Faith No More, but as I’ve become more aware of how much of the downtown NYC cool I once idealized doubles as a smoke screen for bullshit, I’ve come to appreciate how upfront L.A. is, its bullshit generally undisguised save for a light application of gold leaf.

Lewis’ songwriting is no more narcissistic than, say, the cars-and-booze romanticism of the Hold Steady’s Craig Finn—she’s just more willing to serve it straight, gambling that if she’s unflinching enough, it will connect, because self-absorption is a universal burden as much as it is her specific one.

It’s tough to choose a favorite from the album’s first half (it flags a bit in the middle), but mine is “Late Bloomer,” a yarn about a bisexual three-way on a teenage escape to Paris. Its lilting, winding tune reminds me of Marianne Faithfull’s classic version of “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan,” which is about an older woman (“at the age of 37”) regretting never having had those bohemian experiences. Lewis hasn’t missed any chances, and just past 37 herself, she looks back with affection on her adventure. But she’s also aware she’s lucky to have come through unharmed—that this “furious and restless” teen in her “Chelsea Girl haircut” was a bit out of control among these sketchy adults murmuring about “that fire burning in you, little child,” in the middle of the AIDS crisis. Factual or not, the story is charged—at one point Lewis feels obliged to interject, “Forgive me my candor,” before admitting, in italics, “I just had to have her.”

Lewis has been working through such stories about her youth since she started writing, and with good reason. I think her backstory helps explain people’s ambivalence toward her, an unspoken class anxiety about whether this is a privileged girl whining about first-world problems (insomnia, her band breaking up, etc.) or someone who made her way up on her own. The answer is both, in a peculiarly Hollywood way.

Lewis’ parents were third-class showbiz, a peripatetic Sonny and Cher–style duo. After they broke up, her father (once one of the Harmonicats) stayed on the road while her mother went on welfare—until Lewis was almost randomly recruited as a child actor, eventually making them wealthy. As Lewis has explained in interviews and songs, that money was squandered. She became estranged from her mother (who fell prey to bad habits), quit acting, and discovered a substitute family and renewed vocation in Rilo Kiley.

In that light the fury and self-sabotage of that 16-year-old in “Late Bloomer” takes on broader meaning, along with Lewis’ other quandaries about identity and how to be. On “You Can’t Outrun ’Em,” composed after her father died, she sings, “I am living proof that history repeats,” trying to reconcile with her parents’ missteps through her own experiences of how bohemian paths can go astray.

As her state’s great portraitist Joan Didion wrote of Patty Hearst in “Girl of the Golden West”: “This was a California girl, and she was raised on a history that placed not much emphasis on ‘why.’ ” Lewis comes from that kind of stock, and her artistic fixation is seeking possibilities to answer that absence, at least provisional ones. Some listeners might want more, a clean four seasons rather than a gnawing unsolvable heat—the bare sun that climbs and falls through her stories like Sisyphus’ stone. But then you’d miss the summits, when it bathes the landscape in italicized light.

So it makes more than just regional sense that Lewis’ sound has moved from the explicitly, artily arresting guitar rock of “Portions for Foxes” to The Voyager’s smoothness, described by one critic as “background music for a sand bar.” The sophistication of these kinds of pop arrangements is that they leave the engagement level up to the listener, as opposed to the with-us-or-against-us clench of indie rock. Lewis still wants to be understood, but she no longer insists.

Being in the unusual condition of having felt both the desperate scrape at the bottom of American life and the airlessness of its heights, she’s disinclined to anchor her adulthood on a tribe. She has to work out a third way for herself—which might be another typical American mistake, but at least it is her own. You can closely track the signposts of her quest, or lean back and enjoy the trip, but she’s not going to brake for you, either. That’s not what ladies do, not when they know the risk that, as Lewis sings on The Voyager, “Where you come from gets the best of you.”