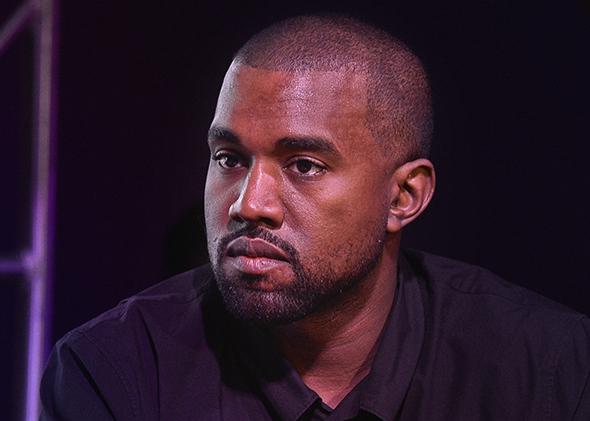

In late May 2013, on the eve of the release of his sixth solo album, Kanye West sat down with New York Times music writer Jon Caramanica and gave one of the most memorable interviews of this past year. It was a brilliant, obnoxious mix of cartoonish overstatements and grandiose aphorisms, most of which were—like so much of West’s career—more right than wrong. At the interview’s end West declared, with characteristic modesty: “I understand culture. I am the nucleus.”

Shortly thereafter, the nucleus went nuclear. In mid-June West unleashed Yeezus, one of the most confounding and aggressively alienating albums ever released by a major pop artist. Lyrically it was an ill-humored stew of scattershot anger, juvenile shock-peddling, and preening, grotesque misogyny. Musically it was a revelation, a work of bruising and savage beauty—seething, incendiary, new. Taken as a whole it felt like a paradox, a work born of stunning confidence yet ravaged by petty insecurity. Many people hated it; many others loved it, but reservedly; Lou Reed loved it nearly unreservedly, a stance that now seems vaguely portentous. Six months later, confusion still abounds. The album has appeared on countless year-end lists but the placements feel halting and apologetic: apologetic for putting it on at all, apologetic for ranking it first, apologetic for putting it on but not ranking it first.

Many years from now, when people talk about Kanye West—and oh, they will—2013 will loom large in their tales. This year West commanded the cultural conversation to a degree rare for a pop artist and unprecedented for a hip-hop artist. Yeezus was the most widely discussed album of the year, the most widely discussed album since West’s last album, and the work and its maker sparked conversations about the place of hip-hop in the cultural hierarchy, the complex interplay of race, class, and social capital, whether something like a poly-artist might exist in contemporary culture, whether only something like a poly-artist might exist in contemporary culture. Yeezus also probably inspired more far-ranging and necessary discussion of misogyny in hip-hop than any album before it, although still probably not enough, nor soon enough. (For all Yeezus’ sins, the self-pitying woman-bashing of 2008’s 808s and Heartbreak, dressed up as emo truth-telling, seems perhaps more insidious and probably more influential.)

Photo by KellyReeves/Flickr via Creative Commons

Through it all West has emerged, unmistakably, as the first hip-hop star to be widely spoken of in the terms of genius. Whether or not we agree with this is beside the point (I think the mantle is deserved, but find it deeply unjust that he’s the first to receive it): It has happened, and it is hugely significant. His ascendance is evidenced by the amount and diversity of attention his work attracts, the extreme critical and cultural benefit-of-the-doubt extended to him, preciously rare for any artist in any form. When Yeezus dropped, its most immediately beloved track was the closer, “Bound 2,” the hit buried at the end and the nearest thing the record offered to “classic” Kanye. There was the cleverly obscure soul sample, the lovely hook from Charlie Wilson, the irrepressible play of the lyrics, knowingly sending up his own tabloid romance: “Yo, we made it Thanksgiving / Maybe we can make it to Christmas.” A perfect line: funny, stupid, arrogant, simultaneously self-aggrandizing and self-deprecating. It doesn’t even bother to rhyme.

Then last month the video came out, four minutes of West and his fiancée, Kim Kardashian, having what must be unpleasantly nerve-wracking sex atop a speeding motorcycle, careening through the world’s most garish Trapper Keeper. It seemed the latest and greatest installment of Kanye West Goes Too Far, until renowned art critic Jerry Saltz weighed in, dubbing the video “the New Uncanny,” comparing it to Jeff Koons and Lars Von Trier, and suggesting it deserved a spot in the next Whitney Binennial. At which point we all nodded vigorously, then slunk away to quickly delete our Trapper Keeper tweets. And that is the kind of year it’s been for Kanye West.

Both in spite of and because of everything above, West also pisses a lot of people off. He’s the avant-gardist and the Internet commenter rolled into one, visionary, vain, and perpetually aggrieved, a man who’ll complain that he should be even more famous than he is in one breath, then complain about everyone else’s celebrity-obsessed culture in the next. He comes off as an asshole, and not in the cool aloof way that Dylan came off as an asshole once upon a time, where you watch Don’t Look Back and think, yeah, but he would have been nice to me. I’m not sure there’s ever been a star of West’s magnitude so lacking in conventional “star power,” that magnetizing-yet-distancing distancing quality that cordons off its holders from the vulgarity of common judgment. West isn’t lacking in sanity, he’s lacking in social graces, and for all his hunger for adulation he’s oddly unconcerned with personal appeal. In an era in which the very idea of likability has been worn away by billions of unthinking mouse-clicks, he’s something like post-likable.

Last Friday, the music world experienced its most seismic happening since Yeezus, when Beyoncé released her latest opus, Beyoncé, with no advance warning or promotion (you might still have heard about it). At the time of this writing the dust hasn’t settled, and may not for a while. Beyoncé is a magnificent album, brilliantly executed and enormously enjoyable, easily the most explosive bundle of musical star power released this year. Track-for-track it is probably the best album Beyoncé’s ever made, fulfilling and surpassing expectations, a resounding affirmation of what now must be considered the most powerful consensus in pop music.

I bring this up because in all these ways—to say nothing of its much-debated but at least existent feminism—Beyoncé feels like the anti-Yeezus, a consensus-shattering work if ever there was one. I also bring it up because one of the most notorious events in West’s enfant terrible portfolio involved Beyoncé quite centrally, and speaks to West’s importance to 2013 and beyond. In 2009 West rushed the stage at the MTV Video Music Awards to protest Taylor Swift’s “You Belong With Me” winning Best Female Video over Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies,” a result that in our current context seems frankly unfathomable.

In true Kanye fashion, he was right; it was every way he went about being right that was wrong, and those ways are what we remember. But part of what caused West to lash out that night was his own recognition that the music industry relies on the creative labor of black artists to a disproportionate degree, while each year heaping disproportionate prestige and commercial advantage onto white ones. As Michael Arceneaux recently argued in an online piece for Esquire, this trend has lately coursed through pop music with a vengeance, and as Chris Molanphy points out over at the Slate Music Club, no black artist topped the Billboard Hot 100 in 2013.

One of West’s favorite talking points is that he’s never won a Grammy when going up against a white artist. It’s not actually true, but it’s true that he’s never won the Grammys’ crown jewel, Album of the Year. The last time West was eligible, for My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy in 2012, he wasn’t even nominated, despite having made one of the best-reviewed albums in history. That year the award went to Adele, a white British soul singer. In fact, it’s been 10 years since Album of the Year went to a rap album, and the list of hip-hop artists who’ve never won the award at all can be summed up as “everyone who’s not Lauryn Hill or Outkast.” That may change this year, as (drum roll) Macklemore and Ryan Lewis are favored to win for the increasingly aptly named The Heist. West, once again, isn’t nominated.

West’s thin-skinned vanity, unseemly scorekeeping, and obsessive grievances may have been the defining aspects of his public persona in 2013, but they shouldn’t be so quickly discredited: At a time when we’re too often content with smarmy symbolism and well-learned politesse, Yeezus is raising hell. Nor should they drown out the music he made, courageous and difficult and hellraising in its own right, music that will outlast any of us, even the nucleus Himself. As West remarked in that Times interview all those months ago, “I am so credible and so influential and so relevant that I will change things.” In 2013, Kanye West was the genius we deserved, even when we didn’t. Maybe we can make it to Christmas.