I once ran into David Bowie on the street in New York City about 10 years ago. He was walking down the Bowery with a hood pulled over his head, avoiding eye contact and moving swiftly, the way famous people do. That same year, I ran into Lou Reed in midtown, Brian Eno at JFK Airport, and Philip Glass on the F train, but none of those moments were as jarring as passing by David Bowie on the Bowery. It felt strange to see him bounding down the street like a normal person. Perhaps the man who fell to Earth was human.

Bowie retains a potent mystique, the whiff of übercelebrity. He possesses a certain coolness—in both the cultural sense and the emotional one. Bowie seems less “real” than other classic rock stalwarts, like the Rolling Stones; his slight otherworldliness keeps him intriguing. “My statement is very pointed—except it’s very ambiguous,” Bowie said to NME in 1975. That pointed ambiguity lingers four decades later; at some level, we still don’t know who David Bowie is. The cool distance he injects between himself and his audience is part of his enduring seduction.

Bowie is a master at the art of the mix, picking up fragments from culture—literature, art, film, music, fashion—and melting them down into something that sounds like no one else but him. At several points in his long, storied career, Bowie defined the zeitgeist, and his constant shape-shifting worked in his favor. “I never thought of myself as a futurist,” he said to Melody Maker in 1978. “I always thought I was a very contemporary sort of figure, very Nowish. Rock is always ten years behind the rest of art; it picks up bits and pieces.”

At his best, Bowie didn’t chase after trends; he helped to create them. In 1977, Bowie was in Berlin with Brian Eno and Tony Visconti brewing strange synthesizer epics and experimental rock songs, not in London where punk was exploding. In the 1980s and 1990s, Bowie jumped on trends with mixed results, in albums like 1997’s drum and bass-influenced Earthling.

The Next Day, Bowie’s first album in 10 years, appears Tuesday, seemingly out of nowhere. Instead of releasing a dubstep album to keep up with the kids, Bowie hews close to his classic work in the 1970s without sounding like a retread of the past. The Next Day is the best album Bowie has made since the curiously underrated Outside, produced with Eno and released in 1995.

Produced by Visconti, whose fruitful partnership with Bowie extends back to Space Oddity in 1969, The Next Day is, by all measures, a huge success. On the pop charts, Bowie is reaching heights he hasn’t hit since the ‘80s; in the press, the album is garnering nearly universal critical acclaim. “David Bowie’s The Next Day may be the best comeback album ever,” declared Andy Gill in the Independent. In Rolling Stone, Rob Sheffield enthused that Bowie’s latest single “The Stars (Are Out Tonight)” was “like Bowie decided to fuse ‘Heroes’ and ‘Space Oddity’ into the same song, a feat he’s never attempted before.” The Telegraph pronounced the album “an absolute wonder.”

The Next Day is indeed a great album. But the hosannas are a bit surprising, given the limp reaction to Bowie’s previous two rock albums, Heathen and Reality, which were also produced by Visconti. The albums had strong moments but went largely unnoticed. Part of the problem with Reality—an album that was, in part, a meditation on the world after 9/11—was that we didn’t want Bowie’s reality. We wanted artifice, camp, fantastical stories, and soaring anthems. Earnestness and candor are boring; we craved a grander illusion, one that Bowie is so expert at architecting.

The Next Day is a propulsive rock album with stronger songs and more drama. Many of the songs on The Next Day are not autobiographical but are tales culled from Bowie’s readings of medieval English history. These age-old stories are often harrowing, visceral: In the album’s title track, Bowie howls “They chase him through the alleys chase him down the steps/ they haul him through the mud and they chant for his death/ drag him to the feet of the purple-headed priest.” Narrating dark tales based loosely on history, or on great works of fiction, is an old Bowie technique: 1973’s Aladdin Sane was full of vignettes, most memorably “Panic in Detroit,” which took its cue from Iggy Pop’s tales of the White Panther party, and 1974’s Diamond Dogs drew inspiration from George Orwell’s 1984.

Another reason for The Next Day’s remarkably successful reception is time. After 10 years of silence from Bowie, we craved his presence—not just as music fans but for our culture at large. We missed him, and we wanted him back.

“Here am I, not quite dead, my body left to rot in a hollow tree,” Bowie announces on the album’s bracing opener. He’s telling a story, of course, but several critics have taken Bowie’s forceful words as evidence that he is commenting on his own mortality, the passing of time, and perhaps his health. (He suffered a heart attack in 2004.) But the theme of death is a familiar one for Bowie: He has been singing about mortality since the beginning. Dark, dystopian themes pervaded Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold the World; 1972’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars played heavily with themes of life and death. “We are the dead,” Bowie sang in Diamond Dogs—an album that opened with Bowie creepily intoning “And, in the death, as the last few corpses lay rotting in the thoroughfare … ” and closed with the ghoulish lock-groove loop of the “chant of the ever-circling skeletal family.”

The Next Day’s elegiac first single, “Where Are We Now?” is the album’s most personal song, conjuring his storied past in Berlin in the 1970s, the spiritual home of the “Berlin trilogy” of albums (Low, Heroes, and Lodger) made with Eno and Visconti. “Sitting in the Dschungel on Nürnberger Strasse, a man lost in time near KaDeWe,” Bowie sings. His lyrics are loaded with landmarks in space and time: The Dschungel was a well-known club in West Berlin where Bowie, Iggy Pop, and many other famous rockers and artists hung out, and KaDeWe is Berlin’s iconic department store, which outlasted both World Wars to become a symbol of the city in the 20th century. It’s rare for Bowie to sound this wistful about his deep past in a song; Bowie is usually hesitant to discuss his own history. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London is mounting a major Bowie retrospective later this month, and he is not expected to attend the opening.

The Next Day offers a tantalizing window into the Bowie of the 1970s. The album is densely self-referential, though many of the references are sonic rather than lyrical. One song ends with the unmistakable shuffle of “Five Years”; another song recalls the swing of “Drive-In Saturday.” “Dirty Boys” sounds like vintage Iggy Pop circa The Idiot—an album Bowie famously produced with Visconti’s help.

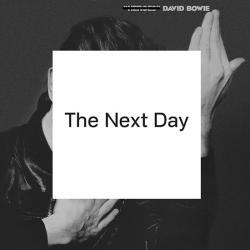

The cover art, too, travels directly into the memoryscape to the Bowie of yesterday—the angular, black-and-white portraiture of 1977’s Heroes, his iconic face blanked out with a white square. It’s a clever reference not only to the past but to the common perception of Bowie as a blank slate, a canvas onto which his various personas are projected. A sly full-page advertisement for the album in the Guardian last week played with that notion, putting the album cover front and center with the words “Your idea of David Bowie here” written across his face in the white space.

But Bowie isn’t a blank slate. Read old interviews and he talks in great detail about his creative process. He’s deeply engaged with art, music, and film—not just as a producer but as a deeply committed fan who can nerd out about Renaissance art, Fassbinder, Buster Keaton, Scott Walker, Kurt Weill. In the 1990s, he moonlighted as an arts journalist for Modern Painters and traveled to Switzerland to interview the late, enigmatic painter Balthus.

We can take Bowie at face value—he invites us to—but dig deeper and there’s more to the picture. We can doubt his sincerity, his myriad poses, the constantly shape-shifting celebrity that Lester Bangs once called “pure Lugosi, eyes glittering, ready to strike.” But if Bowie seems difficult to decode, it’s because his best music gives words to the strange, conflicted feelings we weren’t able to explain ourselves. In 1978, when Melody Maker took him to task for a “chilly, technological feel” to many of his records, he responded “I don’t think they’re chilly emotions—I think they are just rather surprising emotions that are lurking in one’s head that are very rarely expressed, possibly because one doesn’t feel there is an occasion to express that kind of emotion. I still don’t know whether there is an occasion to express that emotion, but I’m expressing it on those records in case anybody needs it!”

After nearly 50 years of making music, Bowie, now 66, has shown he still has a few surprises up his sleeve. The Next Day won’t shift any grand paradigms, but it’s a welcome reminder that Bowie still exists, and he’s still working to refine his vision.

“For me, the early ‘70s period was the thing that gave me my opening,” Bowie told Rolling Stone in 1984. “I don’t think I could ever contribute so aggressively again. But the interesting thing about rock is that you never think it’s going to go on for much longer. I’m 37 going on 38, and I find myself thinking, ‘I’m still doing it!’ So you’re redefining it all the time.”