When I was a child growing up in the 1980s, Ravi Shankar was like a kindly uncle to me. I knew him only through his records; his burly, smiling face adorned the covers of the many Shankar LPs and cassettes that filled my parents’ house. The albums didn’t just offer endless hours of music—they offered lessons, quite literally. On The Sounds of India LP, released in 1968, Shankar talks us through Indian classical music, patiently introducing its complexities. “Ragas are precise melody forms,” Shankar says in precise, careful English. “A raga is not a mere scale—nor is it a mode.” I learned what a raga was from listening to Ravi Shankar, and millions of other people did, too.

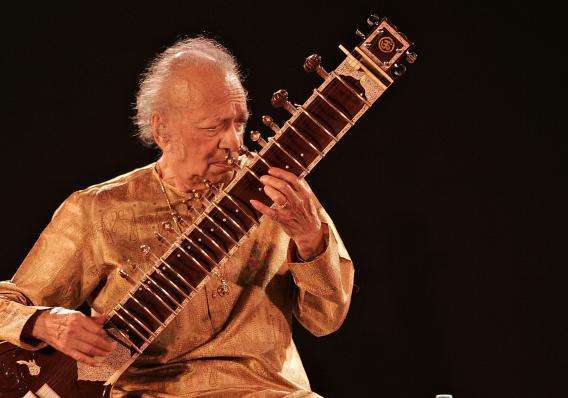

It is impossible to overstate Shankar’s impact on popular music and culture. He was more than a great sitar player; he was an essential bridge from India to the Western world. Shankar was the only South Asian star to achieve status as a bona fide household name in the United States.* No one—not even the biggest Bollywood stars like Amitabh Bachchan—come close. Shankar helped make India matter in the eyes of the West. He helped make generations of South Asian immigrants feel like they mattered.

My parents moved to the United States from India in 1967, from a small village in Northern India to an apartment in Hoboken. Like many others moving to the United States, they were initially bewildered by America and everything in it—the paved, wide-open roads, the crime, the pizza. The West’s then-raging fascination with the East made life slightly easier. My mother wore batik-painted blouses from India, and was surprised at how much people in America seemed to like them. My father played tabla, the traditional Indian drums that often accompany sitar—and by 1967, thanks to Shankar, the sitar was cool.

That was the year that Shankar played at the now-infamous Monterey Pop Festival. At Monterey, Pete Townshend of the Who smashed his guitar at the end of “My Generation.” Jimi Hendrix smashed his guitar, too, and lit it on fire. Shankar played sitar for four concentrated hours. It was just as intense and theatrical, but in a completely different way.

For Shankar, music was all-encompassing. It was everything to him, and he demanded everything from his listeners. He decried the “mind-expanding” chemicals that were rampant at ’60s festivals like Monterey. The music, Shankar argued, was transporting enough. “If one hears this music without any intoxication, or any sort of drugs, one does get the feeling of being intoxicated,” Shankar said in a 1967 interview. “That’s the beauty of our music. It builds up that pitch.”

In the classic 1971 documentary Raga, which my father made me watch as a child, Shankar revisits his guru in India, the famed musician Allauddin Khan. “If you want to learn music, you must leave everything else,” Shankar says. It was a lesson that his guru taught him. Khan demanded nothing less than total surrender. “Those months, years, we spent in his little room, on one piece, one raga, until it became alive,” Shankar says. “And we both would shed tears.”

Shankar was more than the Indian guy who hung out with the Beatles, the sitar player who rocked Woodstock. That stuff is important, of course, and his friendship and collaborations with George Harrison, especially, were sincere and lasting. Some of Shankar’s best work happened before the 1960s—in his collaborations with the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, and in his scores for Satyajit Ray’s classic Apu film trilogy. In Pather Panchali, the sounds Shankar creates are often extremely minimalist, even jarring. Much of Shankar’s best work happened after the 1960s, too—a massive body of work that was always varied, intense, interesting. His music continues to have new relevance for new generations of listeners.

Shankar continued playing and teaching until his death at the age of 92. He seemed ageless, practically eternal. Last year, he was funny and sprightly in an interview with The Guardian, name-checking Lady Gaga as a recent artist he had heard. When asked what advice he would give to a young musician, he responded “I wouldn’t give them advice; I would learn from them.” We are all still learning from Shankar’s long, rich legacy.

Correction, Dec. 12, 2012: Due to an editing error, the piece originally and incorrectly referred to Shankar as South Indian. (Return.)