Beck’s new album, Song Reader, contains no actual recordings. It’s an album of sheet music, 20 songs in total, handsomely packaged in a navy blue hardback portfolio. Each tune is printed on thick white paper in individual pamphlets, complete with hand-drawn color illustrations and amusing asides. The songs have titles like “The Last Polka” and “America, Here’s My Boy.” There are references to real songs from the late 1800s, whimsical snippets of other hypothetical songs, and elaborate fake period advertisements. The package is pleasing to the touch—a deluxe, relentlessly tangible object issued by the indie book publisher McSweeney’s just in time for Christmas.

When you hold Beck’s old-timey paper “album” in your hands, you can almost feel the amount of time and care that was clearly put into it. It’s more than a quaint retro pastiche. But it’s not a revolution, either.

Song Reader is charming—even sort of funny. You can almost imagine it as a plot twist in an episode of Portlandia—Fred Armisen transcribes all of his vinyl records into sheet music to one-up his indie neighbors with his retro cred. “The pop of the early 20th century had a different character,” writes Beck in the long, earnest preface. The songs back in this golden era, he muses, included “thousands of ‘moon’ songs, exotic-locale songs, place-name songs, songs about new inventions, stuttering songs—but even though much of the music was formulaic, there was originality and eccentricity as well.” (Song Reader also includes an introduction by Slate music critic Jody Rosen.)

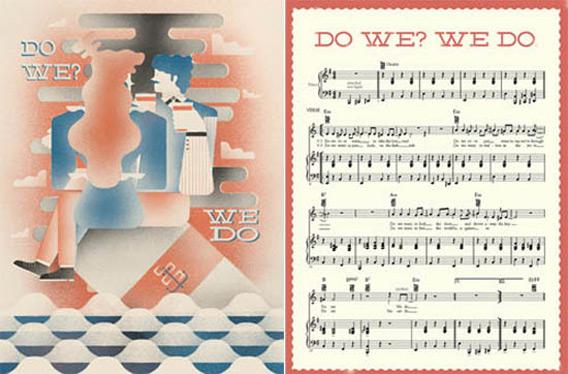

In another sense, Song Reader is as brilliant as it is obnoxious, a fuck you to the legions of MP3 downloaders who would have otherwise procured Beck’s new album for free within seconds. Want to listen to Beck’s new record? Too bad—you have to play it yourself. There’s a nontrivial barrier to entry: You’ll need to know how to read music, as the songs are written using conventional staff notation. (There are guitar tabs, too.) If you’ve taken a few years of piano lessons, it’s not a big deal. If you’re Jimi Hendrix—who couldn’t read music—it’s a struggle.

So what does the music sound like? I played through the songs on a keyboard, finally putting those grade school piano lessons to good use. They’re solid, catchy tunes, and the lyrics have an old-fashioned, slightly demented charm. (Some sample rhymes, from “Rough on Rats”: “Your crawfish fingers and your dirty dregs/ Your sideways stingers and your wooden legs/ They’re throwing out jewels like rotten eggs.”) Beck has taken pains to appeal to beginners; the majority of the songs are in C or G major. Some of the songs are more involved—“We All Wear Cloaks” sports a tricky 7/4 time signature; “Old Shanghai” includes additional parts for horns and ukulele. The guitar tabs are pretty basic; if you can play open chords in G, C, A, and D, then you can get through most of these songs. After two tries, I had mostly mastered my first Song Reader ballad, “Don’t Act Like Your Heart Isn’t Hard.” A prog-rocker pal of mine rolled his eyes after looking at the sheets, deeming them “not complex enough” to be worth his time.

Beck is encouraging people to post the results of their efforts, and dozens of people thus far have uploaded their versions of the songs, via YouTube, on songreader.net. (Beck has recorded demos of the songs on Song Reader, but they haven’t been released.) Many of the versions uploaded thus far, interesting as they are, are largely faithful to the sheet music. The variation comes in the tempo, the instrumentation, the singing, the occasional blunders. One wonders what would have resulted if Beck had instead dispensed with conventional notation and released more abstract graphic scores, like many of the experimental composers of the 20th century. Beck’s own grandfather, the late avant-garde artist Al Hansen, pushed a piano off the top of a five-story building in the 1940s—a famous performance art piece that later became known as “Yoko Ono Piano Drop.” The elder Hansen hung out at Andy Warhol’s Factory and counted John Cage and Nam June Paik as friends. Presumably, he would have thrown the traditional sheet music out the window with the piano, too.

Product shot.

Song Reader encapsulates Beck’s web of contradictions. When I first saw Beck play live—17 years ago at Lollapalooza—he was a smirking twentysomething with a knit cap pulled over his head, mumbling his way through “Loser” while staring at his sneakers. Fast-forward four years, and he’s dancing like James Brown onstage at the VH1 Fashion Awards, yelping at the mic and owning the party. He cycled through countless personas and big-name producers over the years, releasing hit album after hit album, but claims he’s a shy guy. “I was never the guy out all night in bars, hanging out with people in other bands,” he told the New York Times’ Dave Itzkoff in 2008. “I was home watching Antonioni movies, or reading, or going for hikes.” In Song Reader, the guy who once rhymed “tweak my nipple” with “champagne and ripple” on Midnite Vultures gives us antediluvian lines like “The wolf’s on the hill, the baby’s in the briar.”

Another Beck hobby is the Record Club, where he and his friends get together and play a classic album start to finish in a day. (Record Club choices thus far have ranged from Songs of Leonard Cohen to Yanni: Live at the Acropolis.) With Song Reader, Beck seems to want to get everyone in on his Record Club by encouraging listeners to participate in the process of making music. “Learning to play a song is its own category of experience; recorded music made much of that participation unnecessary,” Beck argues.

It’s an odd sentiment for a former sampling maven whose hit albums like Odelay were created with the Dust Brothers—whose production credits include the Beastie Boys’ collage masterpiece Paul’s Boutique. If anything, recorded music enabled new forms of participation to happen—sampling, DJing, and remixing, for starters. With sampling, you could “play” a recording like an instrument. Recorded music made hip-hop possible—hip-hop got its start, after all, with two turntables and a microphone.

Which is another way of saying that sampling helped make Beck’s career. Want to play “Jack-Ass,” one of Beck’s best-known songs? It’s tough to notate in sheet music because it relies heavily on a looped sample of a song from 1966—Them’s cover of Bob Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” Beck’s song is more than the melody; it’s the grain of the sample itself, the watery timbres, the hazy soft-focus memories implied by the ‘60s riff.

The advent of recorded sound upended our notions of what music could be. Rock, jazz, hip-hop, dub, reggae, disco, and most other popular genres born in the past century are tied to recordings; their life is not in sheet music. Recorded music gave us an array of new possibilities, new sounds, and new confusion about authorship.

Song Reader takes us back to an era when sheet music was king. In this simpler, seemingly halcyon time, friends would gather around a piano in the parlor and play popular songs together. Sheet music served another purpose, too; it was a commodity that could be bought, sold, attributed to a single author, and copyrighted. (The copy machine was decades from being invented.)

Product shot.

Song Reader was partly inspired by the story of a song called “Sweet Leilani,” released by Bing Crosby in 1937. “Apparently, it was so popular that, by some estimates, the sheet music sold 54 million copies,” Beck marvels. “Home-played music had been so widespread that nearly half the country had bought the sheet music for a single song, and had presumably gone through the trouble of learning to play it. It was one of those statistics that offers a clue to something fundamental about our past.”

The funny thing is, Bing Crosby couldn’t read sheet music. He wouldn’t have been able to sing his best-selling “Sweet Leilani” from the notation. By all accounts, Crosby had a great ear; he could apparently learn a song after hearing it once. Crosby became increasingly dependent on recording and eventually helped to ignite the recording revolution in America.

In the late 1940s, Crosby wanted to prerecord his popular radio shows, so he could play more golf and spend more time with his family. The lacquered transcription discs of the era, used for voice recording, didn’t sound good enough. But tape machines were capable of capturing high-quality audio, which could then be edited. In 1947, Crosby saw a demo of the German Magnetophon tape recorder in action and was highly impressed; the Germans made the best tape machines at that time. Crosby quickly realized that tape recording was the key to more golf. In 1948, Crosby helped kick-start Ampex, the legendary American tape-machine maker, which was then in its early stages, by cutting the nascent company a check for $50,000.

In some small way, Crosby helped make Beck possible. Few artists are more savvy about the possibilities of the recording studio than Beck; he routinely collaborates with top producers like Nigel Godrich and recently took a turn as a producer himself. In 2002, Beck broke up with his long-term girlfriend, and fun party-music Beck made way for painfully sincere acoustic-guitar Beck. But the “stripped-down” sound of the resulting album, Sea Change—made with Godrich’s help—is just as painstakingly constructed as Beck’s sample-heavy records. Listen closely and you’ll hear the subtle effects on the vocals, the layers of overdubs, the reverb on the guitar. It is a product of the recording studio, just like everything else Beck has done.

Song Reader is the latest signpost of the new earnestness in our culture, a culture that McSweeney’s is a part of, too. Like pickling, building your own furniture, or painstakingly recreating cocktails from the 1920s, Beck’s Song Reader encourages us to work on a craft, to revive a bygone era. It’s not a bad thing—it’s a constructive impulse, and a sincere one.

Take it as an opportunity to spend a few fun hours with a sibling during the holidays, or use it as an excuse to pick up a guitar again, or even as a way to think a bit differently about what it means to live in the age of recorded music. Just don’t mistake it for a manifesto.