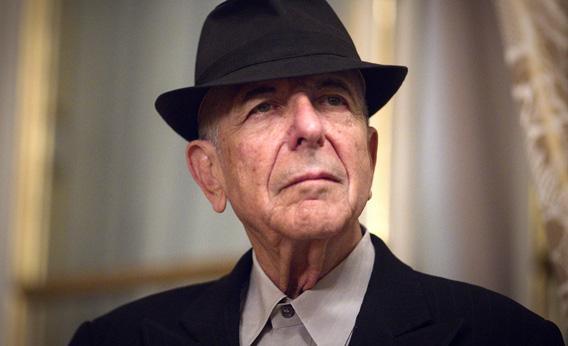

On the occasion of Leonard Cohen’s death, Slate remembers the artist with a reprint of this 2012 post:

Check out our Spotify playlist of the Leonard Cohen songs discussed in this essay.

Leonard Cohen has a new album out: Old Ideas, his 12th, and his first in seven years. He’s 77 now, and if you know Cohen you know his age will get its due in the new songs. The title, of course, has a double meaning, the second being that these songs are ideas about getting old. His life is his wellspring, and life has amounted to a long and singularly winding road for this troubadour.

Born in Montreal in 1934 of Polish and Lithuanian Jewish parents, Cohen was first a modestly successful poet. He learned guitar to pick up girls and got into songwriting partly because he was tired of being poor. His first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, came out in 1967, when he was 32. Probably it got green-lighted in the wake of Bob Dylan’s success, when Dylan had demonstrated to record executives that you could make highly personal, elusively poetic, scraggly sounding records that the public would buy. Of course, Dylan was riding a folk wave when he emerged in the early ’60s, and Cohen caught that wave too.

I’d like to compare those two, in the process of looking back over Cohen’s life and songs. He and Dylan have been working for decades without any visible connection or competition. In practical terms there is no competition, because Dylan has been by far the more visible and influential artist. But if Cohen has always sung in the shadow of Dylan, in the quality of the work I suggest he has been in nobody’s shadow.

A long career has done Cohen well by me, and I imagine a lot of listeners. In the ’60s and ’70s, I liked a few of his songs well enough, though I found the voice and the tunes not as striking as Dylan’s brassy honk and his unforgettable melodies in the folk days. “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Mister Tambourine Man,” any number of Dylan songs seemed timeless, as if they’d evolved through many voices over many years. (Some, including “Blowin’ in the Wind,” were based on traditional tunes.)

Cohen didn’t do that, probably couldn’t do that. He was never the tunesmith Dylan was, and in the early years his voice actually made Dylan’s sound pretty good. Cohen sang in a tenor you could call “reedy” if you wanted to be nice, “nasal” if you didn’t. They’re both mediocre guitar players; any number of high-school students could play rings around them. Cohen’s melodies tended to start at the bottom of his range, ascend toward the top of his range—which was not very far—then descend and screw around in the lower region for the rest of the verse. His early hit “Suzanne” is a case in point.

The lyrics were a different matter. Few if any Cohen songs would make a dent if not for the words. His first book of poems came out in 1956, when he was still an undergrad at McGill. Since then he has published several books of verse, plus a couple of novels in the ’60s. The experience has contributed to who he is: one of the finest, most distinctive, most authentic poets to write popular song in English in the last century or so. For one example of why, recall “Who By Fire?,” his meditation on untimely death and the ultimate unanswerable question.

And who by fire, who by water,

who in the sunshine, who in the night time,

who by high ordeal, who by common trial,

who in your merry merry month of May,

who by very slow decay,

and who shall I say is calling?…

And who by brave assent, who by accident,

who in solitude, who in this mirror,

who by his lady’s command, who by his own hand,

who in mortal chains, who in power,

and who shall I say is calling?

Who else in our time would or could write a lyric like that?

To put Cohen at the top of his trade is not to forget classic American song lyrics like the wordplay of Ira Gershwin or Cole Porter. But I wonder how often either of those geniuses, for such they were, actually meant what they wrote: “In time the Rockies may crumble,/ Gibraltar may tumble,/ they’re only made of clay,/ but our love is here to stay.” That’s from Ira Gershwin. It is, I submit, exquisite bullshit, music in itself. And I wonder in what respect Dylan means “Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot/ Fighting in the captain’s tower/ While calypso singers laugh at them/ And fishermen hold flowers.” You wonder sometimes if Dylan is earnest about much of anything other than his scorn.

There’s an unmistakable sense that Leonard Cohen means every word he sings, in his irony and his cynicism, in his pain and his exaltation. For me, all that didn’t sink in for quite a while. After the mid-’70s I lost track of Cohen. I’m a classical musician, perennially struggling to pursue my craft while somehow paying the rent. For decades, the little time I had to spare for pop music I spent on the Stones, Beatles, Creedence, Joni Mitchell, Dylan, Zappa, et al. Like a lot of people I was too lazy to come to terms with Cohen’s lyrics. Then cruising cable one night about 15 years ago, I came upon him standing in his usual suit, at the foot of a staircase somewhere, behind a little keyboard, singing “Democracy.” It was a dry and understated but strangely powerful performance, and the song slayed me. At the end he was ushered up the stairs by a couple of babes in tight dresses. It was a memorable turn for an aging bard and self-proclaimed ladies’ man.

For the first time I heard Cohen’s new voice, the whiskey baritone that I like better than his old voice. His melodies may still be on the plain side, but the voice says so much more than it used to. In that voice there’s a lot of years, a lot of cigarettes, stimulants, lust, regret, and hard-won wisdom. When he gets spiritual, the voice questions that wisdom but doesn’t destroy it—see “Anthem” and his much-covered “Hallelujah.”

The day after catching him on TV, I went out and bought The Best of Leonard Cohen and More Best of and have been listening to them ever since. I’ve got more songs from various albums in the mix, but mostly it’s those collections and a few of Ten New Songs, from 2001. He put together the best-of albums himself, and he chose well.

If Cohen is the finest poet of our songwriters, he’s hardly a simple or a predictable one. You can never guess which direction a line is going to come from: cynical, surreal, earnest, bitter, exalted—no way to know. Eventually it adds up to a strange sense. Beside Dylan’s flights of fancy and rage, Cohen’s sentiments seem more immediate, more real. Or maybe I just have a touch more preference for Cohen’s familiar depression tinged with something like religion than for Dylan’s wit and wildness and biliousness. A prime example is “Democracy,” the song that brought me back to Cohen.

Look at how the trajectory of the lines builds to an unexpected climax.

It’s coming through a crack in the wall,

on a visionary flood of alcohol,

from the staggering account

of the Sermon on the Mount,

which I don’t pretend to understand at all.

It’s coming from the silence

on the dock of the bay,

from the brave, the bold, the battered

heart of Chevrolet:

Democracy is coming to the U.S.A.

That’s what I mean by never knowing where a line is going to come from. The trajectory of that verse careens among, roughly, 1) surreal/alcoholic, 2) the New Testament, 3) Otis Redding, 4) surreal/economic, before we arrive at the stunning refrain.

None of this is intended to put down Dylan. At his best he’s incomparable. Consider the beginning of “Highway 61 Revisited“:

Oh God said to Abraham, Kill me a son.

Abe say, Man, you must be puttin’ me on.

God say, No.

Abe say, Whut?

God say, You can do what you want, Abe, but, uh,

next time you see me comin’, you better run.

Abe say, Where you want this killin’ done?

God say: Out on Highway 61.

That’s not exact because I’m quoting it from memory. Even at their weirdest, you can often quote Dylan lyrics from memory. This song is sublime in its way, also hysterical. It begins with a succinct send-up of religion before dissolving into surrealism, which is where most of the song dwells.

If Cohen is not as wild a poet as Dylan, he’s closer to the heartstrings—his and ours both. He’s got his surreal side too, but it’s in support of his essential realism. And in many ways he’s gotten better as he got older, which few would claim about Dylan. Cohen’s best songs do what I think popular song ought to do: Capture something meaningful in our lives and put it into melodies worth singing in the shower.

I’ll be adding to my mix songs from Old Ideas as I get to know it. (You can hear it streamed here.) In this one Cohen doesn’t bother with the music so much, and he barely bothers to sing—or maybe his voice is too frayed for that now. He’s homing in on the words, in that sense maybe returning to his roots as a young poet winning prizes and admirers. The valedictory quality is inescapable, starting with the titles: “Amen,” “Darkness.” It begins with “Going Home,” which is a stern and sardonic address to the poet from his muse, or from God, or maybe they’re the same:

I love to speak with Leonard,

he’s a sportsman and a shepherd,

he’s a lazy bastard livin’ in a suit.

But he does say what I tell him

Even though it isn’t welcome—

he just doesn’t have the freedom to refuse.

The song has one of Cohen’s unforgettable refrains:

Going home without my burden,

going home behind the curtain,

going home without this costume that I wore.

Over the decades, Cohen’s songs have steadily darkened, even as five years in a Zen monastery during the ’90s tempered some of his lifelong depression. In Old Ideas, Cohen reaches maybe the deepest black yet in “The Darkness.” Here darkness is at the center of all, evoking death, naturally, but also love and regret: “Winning you was easy, but darkness was the price.” Yet there’s still always a small niche for hope and renewal: “Come healing of the reason, come healing of the heart.” In the new album there’s a kind of aura around every line, a sense of something said once and for all, and it’s not all bleakness, and it’s terrifically moving.

Looking over his songs from the last decades, one has one’s complaints. In some periods I wish there were more acoustics and less synth and slick production. For a while he was afflicted with Phil Spector. To mention another regret: I dearly love “The Land of Plenty” from Ten New Songs, right from its gently wafting opening lick, but I wish he had let this one blossom around its unforgettable refrain:

May the lights in the land of plenty

Shine on the truth someday.

Instead, Cohen takes it into some kind of vaporous personal kvetch:

I know I said I’d meet you,

I’d meet you at the store,

but I can’t buy it, baby,

I can’t buy it anymore.

I have a fantasy that someday he’ll give in and write two or three verses for “The Land of Plenty” that are worthy of its refrain. It could be a song to make things happen, the way “This Land Is Your Land” and “We Shall Overcome” do. But in Ten New Songs he’s generally near his prime. “My Secret Life” and “Here It is” are among the great ones, and “A Thousand Kisses Deep” is becoming the classic it deserves to be.

Love, lust, bitterness, transcendence. In his art the range of his concerns and his responses to life inescapably reflect his experience. The long list of his lovers, short- and long-term, includes Joni Mitchell and Rebecca de Mornay, with a celebrated-in-song encounter with Janis Joplin—“giving me head on the unmade bed/ while the limousines wait in the street.” True, he later regretted those lines (“My mother would be appalled”). In person and in song, Cohen is funnier than you expect. That’s another part of his range, his life. Cohen is reported to be an observant Jew and is an ordained Buddhist monk, and I’m not kidding. Yet some of the most memorable imagery in his songs is Christian:

Here is your cross,

Your nails and your hill;

And here is your love,

That lists where it will.

As for listing, I’m the sort of annoying person who trots out lists of favorites. With Dylan songs I’m not so sure what they are, because the nature of surrealism is that one bit of surrealism is more or less equivalent to another, and his rants and putdowns (see “Positively Fourth Street”) only intermittently entertain me.

But with Cohen I know my favorites. Here are three to illustrate why I call him the finest poet of our songwriters. As usual the lyrics shine while the music is along for the ride—but particularly good rides in these cases.

The one already mentioned is “Democracy,” which is generally the first song I play for people who don’t know Cohen. It invariably knocks them out. Maybe my favorite is “Closing Time,” partly because it’s a terrific tune as tune, actually a fine thing to dance to, thanks to some splendid sidepersons.

It has all Cohen’s fractured, paradoxical brilliance on display. The first verse sets a boozy Saturday-night scene:

Ah, we’re drinking and we’re dancing

and the band is really happening

and the Johnny Walker wisdom running high.

And my very sweet companion,

she’s the Angel of Compassion,

she’s rubbing half the world against her thigh.

And every drinker every dancer

lifts a happy face to thank her,

the fiddler fiddles something so sublime.

All the women tear their blouses off

and the men they dance on the polka-dots

and it’s partner found, it’s partner lost,

and it’s hell to pay when the fiddler stops.

It’s closing time.

That mix of quotidian horniness, Biblical overtones, party trance, and down and dirty jealousy is classic Cohen. But everything turns on that little refrain. It reminds me of refrains in Yeats, one of Cohen’s touchstones: Daybreak and a candle end. In the course of “Closing Time,” the refrain evolves from the closing of a bar to the closing of love to the closing of life:

I loved you when our love was blessed,

and I love you now there’s nothing left

but sorrow and a sense of overtime.

And I missed you since the place got wrecked,

and I just don’t care what happens next:

Looks like freedom but it feels like death,

it’s something in between, I guess.

It’s closing time.

If “Closing Time” is my favorite all in all, the one I call Cohen’s greatest is “Anthem.”

This song doesn’t wander off into personal bitterness and regret. It sets the sights high and keeps them there. It’s a sort of gospel song celebrating the brokenness of life, everything flawed and incomplete, and the possibility of redemption in that. In its refrain there is a kind of truth the like of which is hard to find in popular song.

Ring the bells that still can ring.

Forget your perfect offering.

There is a crack, a crack in everything.

That’s how the light gets in.

I don’t know if the end of that verse comes from some venerable Eastern text. It’s good enough for that, but I suspect it’s all Cohen. In the song, that sad revelation is inseparable from his whiskey baritone, and irony always hovers in the wings. But you don’t forget it. It’s the kind of truth that is cinched by the perfection of its saying. These are words to engrave not on a wall, but on your soul. Here’s what our troubadours can do when they’re truly great, and when they truly mean what they say.