In 1997, an unknown Florida hard-rock group called Creed spent $6,000 to make its debut album, My Own Prison. Talk about a good investment: An independent label, Wind-Up, signed the group, got Sony to provide distribution, and Creed became, for four years or so, one of America’s hugest bands. Its 1999 single, “Higher,” topped the modern-rock chart for 17 straight weeks. “With Arms Wide Open,” released the following year, reached the top of the pop charts, and won the Grammy for best rock song. Between 1997 and 2002, the band grossed more than $70 million touring. To date, it has sold 26 million records in the United States.

It was the perfect setup for a Behind the Music-style implosion, and Creed delivered. By late 2002, singer Scott Stapp was on a near-daily regimen of alcohol and Percocet—prescribed after a car crash—and he would soon add OxyContin and the steroid Prednisone to the list. In December of that year, Stapp stepped onto a Chicago stage visibly intoxicated, slurring his lyrics and performing one song while lying on his back. (Fans sued, unsuccessfully, for refunds.) It was the last show of a nationwide tour, and Stapp’s band mates didn’t speak to him for months. The next year, at home in Orlando, Stapp put two guns to his head, intent on blowing out his brains. Recounting this near-suicide, he has explained that he decided to put down the weapons after spotting a photograph of his infant son, about whom he’d written “With Arms Wide Open.” In 2004, Creed broke up, and as this recent New York Times piece shows, there is no disagreement within the band that it died for Stapp’s sins.

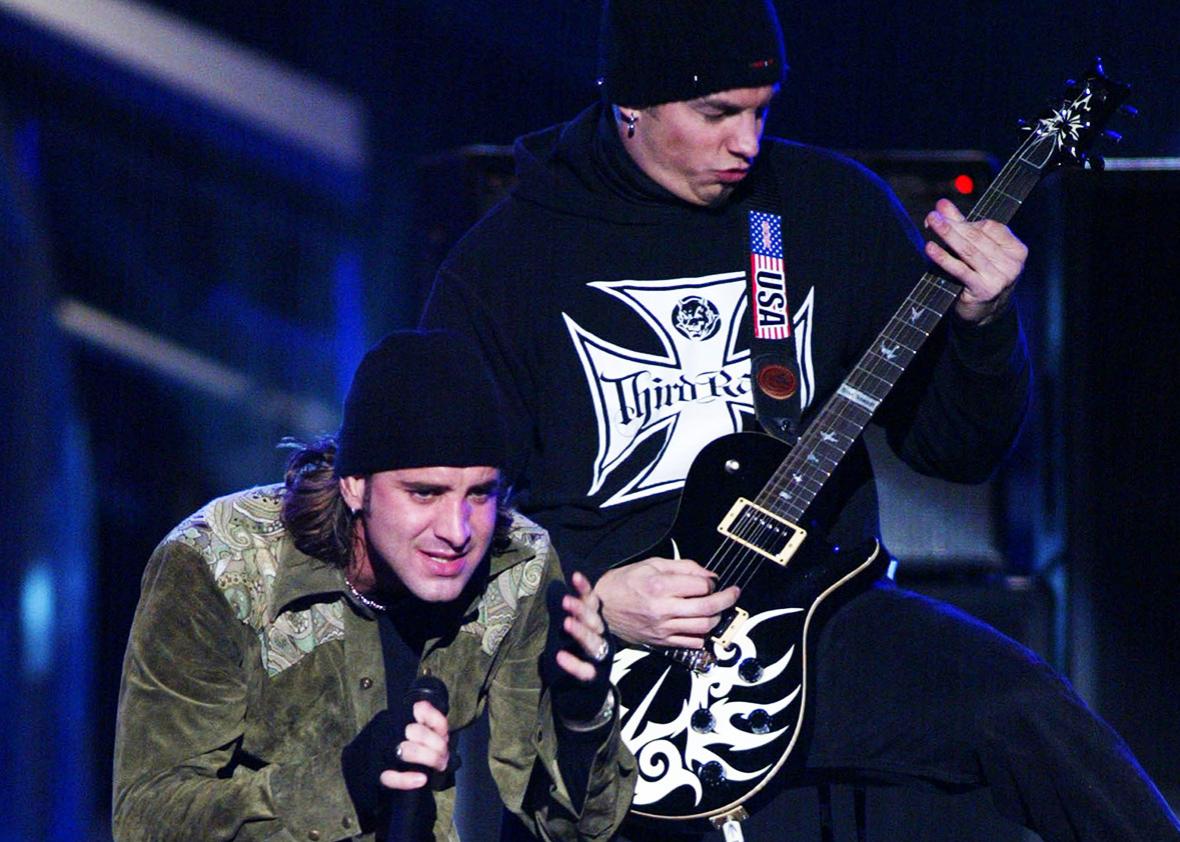

Today, Stapp has shaved his head, cleaned up his act, and Creed has reunited for a tour and a new album, out at the end of this month—the first single, “Overcome,” is a wailing survivor’s anthem. (ThisDetails story is a fine chronicle of the band’s dissolution and return.) Stapp’s lyrics have always been full of sweaty redemption narratives and howled prayers for second chances, so we could have seen this comeback bid coming a mile away. That is, if we’d had any reason to think about Creed at all. From the start, critical gatekeepers dismissed the band as derivative blowhards with a self-righteous Christian agenda, a consensus that did nothing to slow sales but that cemented in the popular imagination and took its own toll. In the Times article, guitarist Mark Tremonti said that he greeted the breakup with a degree of relief: “No matter how many records you sell, when you’re up there with a target on your head every day it’s not fun.” Along with Limp Bizkit (who made fun of Creed, too), Stapp and Co. are remembered today as poster boys for a turn-of-the-century musical nightmare we’re happily past.

There’s no telling whether Creed will make good on its second chance, but the band deserves a second listen. If your impulse on hearing that it has reunited is to groan, stifle it long enough to locate a copy of Creed’s 2004 Greatest Hits collection. It’s a fantastic baker’s dozen of first-rate schlock-rock, courtesy of one of the most underrated and unfairly maligned groups in pop history.

Listening to Creed today, it’s hard to reconcile the animus against the band with the music. (The animus against the group’s satiny tunics and slithery facial hair was always perfectly understandable.) In his lyrics, Stapp is a well-meaning, Bible-fluent doofus, easy to chuckle at but difficult to imagine hating. “The world is heading for mutiny, when all we want is unity,” he sings on “One.” The trouble wasn’t that he was a blustery, would-be messiah (that didn’t stop Bono’s canonization) so much as the unrepentant hamminess he brought to the role: ample baritone quaking and churning, arms outstretched atop mountains and hovering, Christlike, above crowds in music videos. On stage, Stapp was Charlton Heston in leather pants, humping the stone tablets. His brand of fist-pumping, hair-tossing, pelvis-swiveling rocksmanship was hardly without precedent; it just seemed obnoxiously anachronistic. An audacious throwback to the preening hair-metal era (and, even further, to Robert Plant’s roosterish sashay), Stapp audaciously reinflated rock’s hot-air balloon less than a decade after Kurt Cobain was thought to have punctured it for good.

And it’s not that the band didn’t deliver. To the contrary, Creed seemed to irritate people precisely because its music was so unabashedly calibrated towards pleasure: Every surging riff, skyscraping chorus, and cathartic chord progression telegraphed the band’s intention to rock us, wow us, move us. Tremonti was a brutally effective guitarist, and by 2001’s “Weathered,” he’d even added subtlety—or the hard-rock version of it, anyway—to his arsenal. Creed was formulaic, but that’s only an insult if the formula doesn’t work. One of the surprises involved in returning to Creed with a fresh pair of ears is how rocking, exciting, and, yes, moving, the songs can be. “Higher” might turn out to be the nu-grunge “Don’t Stop Believing“: dismissed by cognoscenti on arrival as bludgeoning and gauche but destined for rehabilitation down the road as a triumphant slab of ersatz inspirationalism.

There’s never any such thing as listening in a vacuum—see this recent New York Times Magazine story on the fascinating, ultimately paradoxical attempts of the music Web site Pandora to wean musical taste away from the sullying effects of “cultural information”—and it’s a lot easier to give Creed a sympathetic spin now that they aren’t so ubiquitous or so ubiquitously loathed. In fact, when you listen to the band’s third album, Weathered, with Stapp’s period of self-ruin in mind, its emotional heft is amplified. “Bullets” is a furious blast of metal and one of the most galvanizing persecution anthems ever penned: “At least look at me when you shoot a bullet through my head! Through my head! Through my head!” he howls, presumably at the band’s haters. At the other end of the spectrum is “One Last Breath,” a wounded ballad featuring one of Stapp’s most affecting vocals and a lovely refrain that foreshadows his suicide attempt: “Hold me now, I’m six feet from the edge and I’m thinking, maybe six feet ain’t so far down.” He vaults up an octave on the first “six,” cracking his voice a little in a heartstrings-tugging flourish.

The album’s biggest hit was “My Sacrifice,” a cornball barnstormer on par with “Higher.” It ends with a repeated plea: “I just want to say hello again.” Creed’s previous album, Human Clay, had gone platinum 11 times over, and Weathered was destined to ship 6 million copies, but Stapp already sounded like an underdog. Seven years later, it finally feels OK to start rooting for him.