It’s hard to believe now, but Bruce Springsteen almost didn’t reach stardom. He had a nice local following in New Jersey and, for some reason, pockets of fans in Virginia and Texas, but in 1974, when he entered the studio to begin recording his third album, Born to Run, he was widely seen by industry types and disc jockeys as a carbonated prospect who had fizzled. His first two albums had hardly sold, despite positive reviews. He carried the burden of being labeled the next Dylan by none less than John Hammond, the executive who discovered the original. Springsteen was signed by Columbia as a solo act, but he showed up with a band. Those who saw him in small clubs loved his spirited, tireless live performances, but there were lots of riveting artists who wrote a decent song or two, drew some acclaim, and then faded away.

Springsteen knew that the stakes for the third album were high. Garry Tallent, the bassist in the E Street Band, recalls, “We were ready to be booted from the label.” Keyboardist Roy Bittan remembers that Bruce “felt everything was on the line.” Guitarist Steve Van Zandt says that if the third record “didn’t make it, it seemed obvious that it was going to be the end of the record career.” To make matters more difficult, Bruce’s ambition was as towering as the pressure. He would not settle. Years later, he recalled, “When I did Born to Run, I thought, ‘I’m going to make the greatest rock ’n’ roll record ever made.’ ”

It took him six months during the spring and summer of 1974 to record the title track. Van Zandt now laughs at the thought of it. “Anytime you spend six months on a song, there’s something not exactly going right,” he says. “A song should take about three hours.” But Bruce was working with classic-rock motifs and images, searching for the right balance musically and lyrically. Born to Run marked a change in Springsteen’s writing style. Whereas previously it seemed as if he had a rhyming dictionary open beside him, now his lyrics became simultaneously more compact and explosive. What mattered to him was to sound spontaneous, not to be spontaneous. “Spontaneity,” he said, in 1981, “is not made by fastness. Elvis, I believe, did like 30 takes of ‘Hound Dog,’ and you put that thing on,” and it just explodes.

The alternate mixes of “Born to Run” that are available reveal some of the ways in which Springsteen experimented musically. In one, a female chorus joins him in the background when he sings, “get out while we’re young,” “got to know how it feels,” and “walk in the sun.” Musically, the strings at various points are more prominent than they would be in the final version. It’s easy to see why Bruce rejected this mix: The chorus and strings make the song too ethereal and distance it from the driving force of the beat. In another mix, Springsteen’s lead vocal is doubled, the chorus is still intact, and the strings at the end of the song are even more pronounced. Two other mixes play with the balance of strings and bass. At one point, the band experimented with different sound effects such as streetcars and drag racing.

The earliest live version of the song that is available dates from July 13, 1974, at the Bottom Line in New York, more than a year before a string of shows at the same venue that would astonish the industry. While musically the song is almost set, lyrically it is dramatically different from the final version, so much so that its meaning shifts. After “runaway American dream,” Springsteen sings, “At night we stop and tremble in the heat/ With murder in our dreams.” The song is darker. He is not singing to Wendy, whose name does not appear. The second verse opens, “So close your tired eyes little one/ And crawl within my reach. … [W]e’ll ride tonight on the beach/ Out where the surfers, sad, wet, and cold/ As they watch the skies/ There’ll be a silence to match their own.”

Springsteen is working the themes of loneliness and violence to the extreme. After “boys try to look so hard,” he sings, “Like animals pacing in a dark black cage/ Senses on overload/ They’re gonna end this night in a senseless fight/ And then watch the world explode.” Clearly, he is trying to stay consistent with other songs that he is considering for the album—at the same show he premiered “Jungleland.” The “broken heroes” of this early version of “Born to Run” have “a loneliness in their eyes,” and instead of loving “with all the madness in my soul,” the narrator seeks to “drive through this madness/ Oh burstin’ off the radio.” Sometime between July and the end of the summer, Springsteen transformed “Born to Run.” He told one writer, “I’m still fiddling with the words for the new single, but I think it will be good.” The notes of alienation, loneliness, and violence yielded to love, companionship, and redemption.

Peter Knobler, a writer for Crawdaddy, got an early listen in Springsteen’s Long Branch house. The place was cluttered with motorcycle magazines and old 45s. Over Bruce’s bed was a poster of Peter Pan leading Wendy out the window. The detail is suggestive: “Wendy let me in, I wanna be your friend/ I want to guard your dreams and visions.” To Knobler, the “song sounded huge, like a Spector spectacular. I still couldn’t make out many words, but through a wall or on a cassette Bruce had worked up to simulate a car radio, it sounded to me like Hit City. The end was fairly pulsating and as it faded, Bruce chimed in ‘WABC!’ [AM hit radio] and, honest to God, it sounded inevitable.”

By early 1975, any attempts to shorten or change the song would have been too late, because it had already become something of a hit. Mike Appel, Springsteen’s manager, was eager to get the single airtime on the radio. It had been a year since the previous album, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. On Nov. 3, 1974, Springsteen appeared with DJ Ed Sciaky on WMMR in Philadelphia. Sciaky was an early and boisterous supporter. He had a surprise for listeners that day: the radio premiere of “Born to Run.”

Within weeks, Appel also sent tapes to Scott Muni at WNEW in New York, Maxanne Sartori at WBCN in Boston, and Kid Leo (Lawrence Travagliante) at WMMS in Cleveland. To Leo: “ ‘Born to Run’ was the essence of everything I loved about rock ’n’ roll. Bruce held on to the innocence and the romance. At the same time, the music communicates frustration and a constant longing to escape.” Leo played the song every Friday afternoon at 5:55; one fan remembers it as the start to the weekend happy hour. Nearly two dozen more stations had it by the new year. All this exposure, with no record in sight, made the record company nervous. When listeners heard something they liked, they usually wanted to buy it right away. But in this case, hearing the song on the radio helped build anticipation for the album.

That Bruce and the band had “Born to Run” down is evident from a show at the Main Point in Bryn Mawr on Feb. 5, 1975. Whereas the premiere performance of “Thunder Road” and performances of other songs that would appear on Born to Run later in the year only partially resembled the final recorded versions, the band rocked “Born to Run” as if they had been playing it for years. Bruce had a lot of work ahead of him in the studio, but “Born to Run” was done.

The rest of the album proved just as challenging. “We were recording epics at the time,” recalls Bittan, who along with Max Weinberg joined the band after “Born to Run” was recorded. “I mean ‘Jungleland’ and ‘Backstreets’ are not easy songs to record,” Bittan maintains. “It’s like trying to drive a Grand Prix course: Every time you go around one turn, there’s another.”

Bruce kept struggling to get on tape the sound he had in his head, and at times it seemed like he was ready to give up. Long nights at the studio ended in misery, the atmosphere tense and rancorous. To stay awake, engineer Jimmy Iovine would take a piece of gum, throw it away, and chew on the aluminum wrapping. In the end, Springsteen was miserable: “After it was finished? I hated it! I couldn’t stand to listen to it. I thought it was the worst piece of garbage I’d ever heard.”

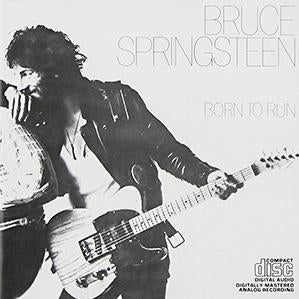

He almost didn’t release it. But Jon Landau, who had stepped in as a producer, helped persuade him to let go. According to writer Dave Marsh, Landau called Springsteen and said, “Look, you’re not supposed to like it. You think Chuck Berry sits around listening to ‘Maybellene’? And when he does hear it, don’t you think he wishes a few things could be [changed]? Now c’mon, it’s time to put the record out.” The album appeared in 1975, and it launched Springsteen toward megastardom, getting him on the covers of Time and Newsweek simultaneously. Reviewing the album in Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus proclaimed, “It is a magnificent album that pays off on every bet ever placed on him—a ‘57 Chevy running on melted down Crystals records that shuts down every claim that has been made. And it should crack his future wide open.”

Born to Run, song and album, fulfilled its destiny. By fusing the pop sounds of the 1950s and 1960s to the generational desires of the 1970s, it defined its time and transcended it. Even Springsteen eventually came around to appreciate what he had accomplished. In 2005, on the 30th anniversary of the album’s release, he admitted that “[i]t’s embarrassing to want so much, and to expect so much from music, except sometimes it happens—the Sun Sessions, Highway 61, Sgt. Peppers, the Band, Robert Johnson, Exile on Main Street, Born to Run—whoops, I meant to leave that one out.”