This week marks the 50th anniversary of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. This piece was originally published on its 40th anniversary.

Thousands of apocryphal tales about Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band have been told and retold in the 40 years since the record’s release, but the loveliest is a true one. Immediately following the completion of Sgt. Pepper’s in the wee hours of April 21, 1967, the Beatles decamped from Abbey Road Studios to Mama Cass’ apartment in Chelsea, where they flung open the windows and blasted an acetate of the album into the London morning at top volume. In the surrounding buildings, windows slowly rose in reply, and neighbors leaned out to listen to the Beatles’ newest songs. It’s a delightful image, a metaphor for the flood of joy and wonderment that the four Liverpudlians loosed on the world, and on England in particular—the windows, the minds, that were nudged open by the Beatles’ sonically questing, love-affirming, sad, funny, irrepressibly tuneful music.

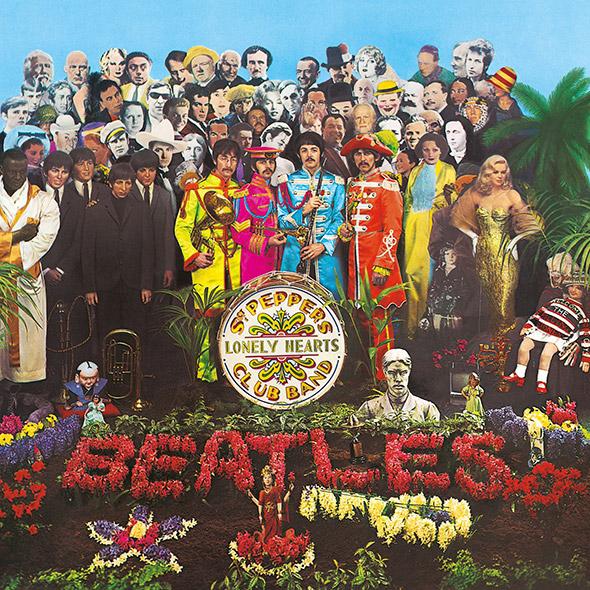

Today, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is so familiar, so encrusted with myth, that we can barely hear it. The album’s 40th anniversary has been greeted by scores of articles touting its historical significance, debates about whether it is “the greatest album of all time” (as if such a thing exists), and the usual talk about its status as pop music’s first concept album. The last notion is demonstrably false. Frank Sinatra was making concept albums back when John and Paul were still knocking around in knee socks, and compared with Sinatra’s LPs such as In the Wee Small Hours, the Sgt. Pepper’s “concept” is, to say the least, loose—the claim is based mainly on the framing device of the title track, which opens the album and is reprised before the stupendous finale, “A Day in the Life.” What cannot be denied is Sgt. Pepper’s influence on subsequent rock and soul concept albums. It’s unfair to blame a record so based in the rigors of pop songcraft, and so full of jokes and mischief and fun, for the ponderous music that was unleashed on listeners in the decades following. But the fact remains that there would have been no Dark Side of the Moon, and no dragons-and-warlocks-themed prog rock epics, had the Beatles not decided to don epaulets for their lark of an album cover and impersonate a vaudeville band.

To be sure, Sgt. Pepper’s has its share of naysayers, and they have been heard from this anniversary season. In a New York Times op-ed article that should be included on the syllabus of Harold Bloom’s next anxiety-of-influence seminar, singer-songwriter Aimee Mann wrote, “As a musician, I’m burnt out on it—its influence has been so vast and profound,” adding that the album lacks “emotional depth” and that she prefers the lyrics of Fiona Apple and Elliott Smith to Lennon and McCartney’s. (No accounting for taste.) Many critics have become similarly disillusioned. The Chicago Sun-Times’ Jim DeRogatis has written (in a phrase that typifies his gentle wit) that the album “sucks dogs royally,” and indeed the reputation of Sgt. Pepper’s has plummeted among rock critics in recent years, with consensus forming around Revolver (1966) as the better Beatles album.

The backlash is based on the wide disdain for Paul McCartney among critics. The truism goes that Sgt. Pepper’s is a McCartney album, a pop confection, full of cute noises and neo–music hall pop, recorded while the drug-addled Lennon was lost in a half-conscious haze. But again, the myth disintegrates on inspection. Yes, McCartney took hold of the reins at Abbey Road, but it was ever thus with Paul, the Beatles’ resident musical cosmopolitan and most dedicated studio rat. You’d be hard-pressed to find more canonical Lennon songs than “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” and “A Day in the Life,” to say nothing of “Strawberry Fields Forever,” recorded during the Sgt. Pepper’s sessions but released as a double A-side single with “Penny Lane.” Meanwhile, those who embrace the cliché that Paul was a spunky and shallow tunesmith—that McCartney composed nostalgia-trip music while Lennon wrote visionary drug anthems—should listen again to Sgt. Pepper’s. Sure, “Lucy in the Sky” has the trippy spiraling keyboard figure and acid-washed words, but McCartney’s eerie little domestic miniature “Fixing a Hole” is more convincingly psychedelic, with the syntactic ambiguities of its lyric mirroring the fractured flitting of an altered consciousness: “I’m fixing a hole where the rain gets in/ And stops my mind from wandering/ Where it will go.” (Is the hole in the roof? Or in his mind?)

Dig deeper into Sgt. Pepper’s, and you find both Beatles frontmen playing against type. The astonishing orchestral “freak-out” in “A Day in the Life”? McCartney’s creation. “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite,” that jaunty music-hall throwback with lyrics cribbed from an old vaudeville poster? A Lennon song. Of course, as with all Beatles records, some of the best moments on Sgt. Pepper’s arise from collaboration that bleeds into competition, the friction between Lennon and McCartney, with their divergent musical styles and clashing dispositions. Who can resist the “Getting Better” chorus, where Paul the Optimist and Skeptical John square off in a cheeky call-and-response? “I’ve got to admit it’s getting better/ A little better all the time,” sings McCartney. “Can’t get no worse,” chimes Lennon.

On both sides of the Sgt. Pepper’s divide—hyperbolically pro and knee-jerk con—there is a tendency to treat the album as an icon stripped of historical peculiarity, floating outside of time and place. Yet Sgt. Pepper’s is the definitive Beatles record not necessarily because it contains their best music, but because it captures them at their zeitgeist-commandeering peak: It is the Beatles album of, and about, history’s Beatles Moment. It’s worth reflecting further on the Beatles’ particularity. Today, the band belongs to the world. But they were an English group, and no album was more local and particular, more steeped in the life and lore of Old Blighty, than Sgt. Pepper’s.

After Revolver, Lennon and McCartney got the idea to write some songs about their childhood in Liverpool. The result was “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane.” With Sgt. Pepper’s, they abandoned autobiography for impish realist—and often surrealist—storytelling. Listen to “Good Morning,” a trip down a middle-class High Street where chatterboxes greet the day with banalities: “Nothing to do to save his life/ Call his wife in/ Nothing to say but/ What a day, how’s your boy been?” Listen to “When I’m 64,” where McCartney’s beautifully observed lines, sung over the song’s most touching minor key lurch—“Every summer we can rent a cottage in the Isle of Wight, if it’s not too dear/ We shall scrimp and save”—resolve with an equally beautifully observed, deadpan-funny rhyme: “Grandchildren on your knee/ Vera, Chuck, and Dave.” Listen to the last verse of “A Day in the Life” (my favorite in the entire Beatles catalog), where Lennon tweaks a found newspaper item into a very British brand of surreal poetry about holes filling the Albert Hall. Even in the kaleidoscope swirl of “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” you can discern an English cityscape, with those “newspaper taxis” plying the quayside and commuters moving through train-station turnstiles. And, of course, the Sgt. Pepper’s brass-band iconography and snatches of music-hall pop are an affectionately mocking tip of the hat to the Olde English past—the Beatles gazing back amusedly at Victoriana.

That British past was a central part of the Beatles story. Ian McDonald’s Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties (easily the best Beatles book) reminds us of the band’s impact in Britain: how four talented autodidacts, fresh from the hardscrabble streets of the urban North, seemingly pulled England out of its postwar malaise by themselves, exploding the lingering rigidities of Victorianism and the class system through the sheer force of their vivaciousness. (Think of the famous lines from Philip Larkin’s “Annus Mirabilis”: “Sexual intercourse began/ In nineteen sixty-three/ (which was rather late for me)/ Between the end of the Chatterley ban/ And the Beatles’ first LP.”)

If Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band doesn’t have a concept, it does have a theme. It’s a record about England in the midst of whirling change, a humorous, sympathetic chronicle of an old culture convulsed by the shock of the new—by new music and new mores, by rising hemlines and lengthening hair and crumbling caste systems. In short, it’s a record about the transformations that the Beatles themselves, more than anyone else, were galvanizing. Playing Sgt. Pepper’s for the umpteenth time, you marvel at what generous-spirited revolutionaries the Beatles were. Compare the “Don’t trust anyone over 30” rhetoric of the Beatles’ 1960s fellow travelers to “When I’m 64,” the sweetest song about old age ever created by a rock group. Then there’s “She’s Leaving Home,” which hitches one of McCartney’s prettiest melodies to a lyric that sympathizes on both sides of the generation gap—with the runaway girl who is “meeting a man from the motor trade,” and with her grief-stricken parents: “We gave her most of our lives/ Sacrificed most of our lives/ We gave her everything money could buy.” It’s a remarkable feat of the artistic imagination, but it may as well have been reportage: Many British parents were saying such things back in the spring before the Summer of Love. Forty years later, if you listen closely, you can hear what Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band sounded like that morning at Mama Cass’ flat in England in 1967. It sounds like England, in 1967.