Think your way back, if you can, to the year that Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre played Coachella and welcomed Tupac Shakur onto the stage to perform a couple of hits. Shirtless, with jeans sagging and his signature “Thug Life” tattoo on his stomach, the legend worked the stage as he did in the ’90s, greeting the audience in his typically profane style: “What the fuck is up, Coachellaaaaaa?!” There was only one problem: Tupac was dead. This was, instead, just an optical illusion, and so everything was just a little off. The “hologram” (which wasn’t technically a hologram) looked and moved just like the “Picture Me Rollin’ ” rapper, but not quite. It sounded just like him, but Coachella definitely didn’t exist in 1996 when he met his tragic demise. It was bizarre, sort of laughable, and slightly unsettling, and yet the audience was supposed to take it seriously.

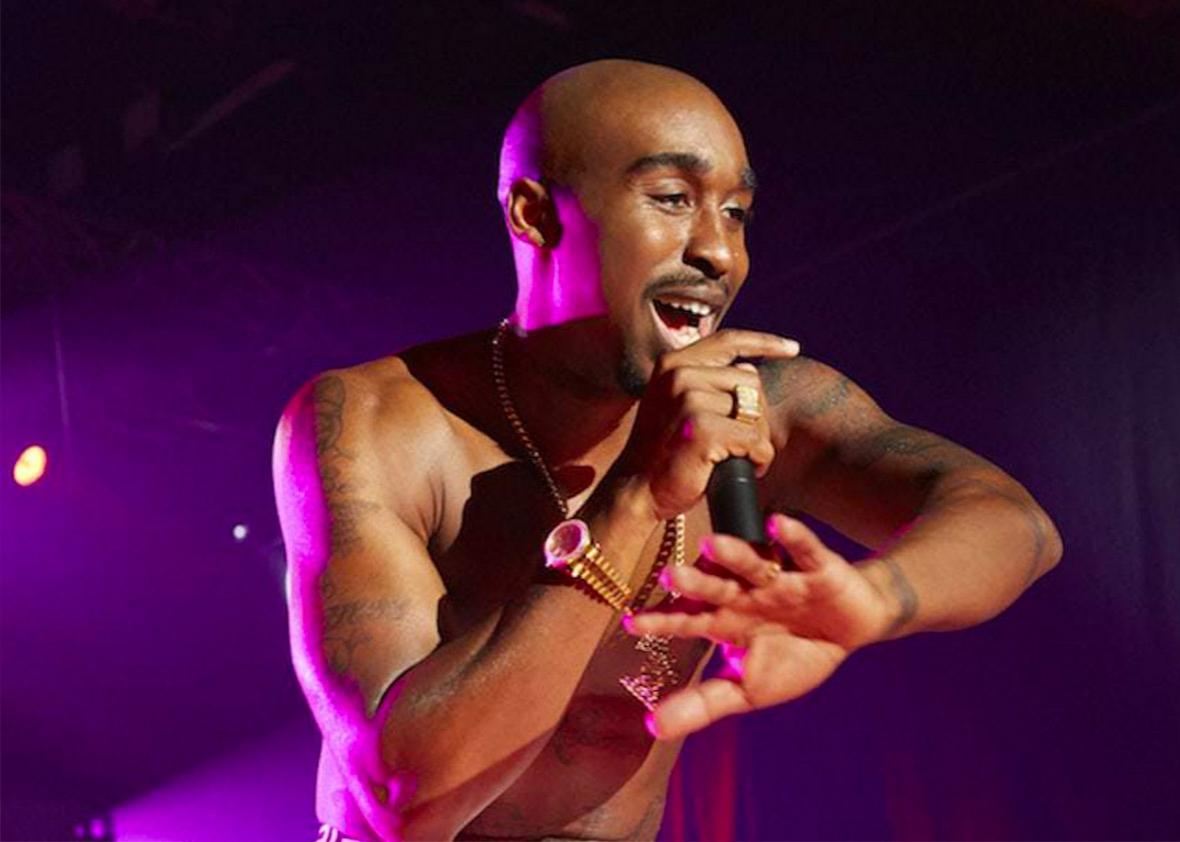

Watching the long-gestated biopic All Eyez on Me is like reliving that experience, except instead of lasting for just five minutes, it lasts for nearly two and a half ridiculous hours. The film pairs grand thematic ideas with pitifully shoddy execution. The FILA gear is present, the original recordings are licensed, and the movie’s star, newcomer Demetrius Shipp Jr., bears an uncanny physical resemblance to his real-life character inspiration. But something—nah, pretty much everything—is off. If the rapper’s fans were hoping for a feature that both honored the legacy of this polarizing figure and recreated some of the magic of the surprisingly entertaining Straight Outta Compton, this is definitely not that movie.

It takes just a few minutes to realize that All Eyez on Me is of only slightly higher quality than a direct-to-DVD movie you’d pick up for a couple of bucks from a Walmart bin. The story opens in 1995 with Makaveli giving an on-camera interview from a maximum-security prison where he is serving a sentence for sexual assault. The reporter’s name and outlet are never disclosed (actor Hill Harper is credited only as “Interviewer”), and this clumsy framing device is only the first of the many poor aesthetic choices that recur throughout the rest of the film. The film dutifully proceeds through the usual stations of the cross, jumping erratically between scenes tracing his origins as the son of Black Panther Afeni Shakur (The Walking Dead’s Danai Gurira, doing the best she can with this mess of material) and his first professional gig as a background dancer with Digital Underground—scenes that function almost exclusively to introduce a new character or plot point and explain, via that interview, how it factored into Shakur’s life.

This “greatest hits” format continues as the film ticks off Pac’s various legal troubles, albums, and movie roles in the crudest ways possible. It doesn’t help that the editing is poorly executed, with abrupt cuts to completely new periods in his life and oddly pedestrian transition music. At one point, with no warning, we’re suddenly thrust into a recreation of his famous hallway scene in Juice, beginning with that locker slam. What in that coming-of-age thriller works as a jump scare that startles audiences elicited instead, at my screening, guffaws.

Other evidence of amateur filmmaking abounds: an overreliance on slow motion. Signposting dialogue, of which there are too many examples to name them all. (Here’s one, which got another guffaw: In the middle of the Juice premiere, Tupac’s manager turns to him and whispers, “This is amazing, Pac. You’re on your way!”) And a moment that borders on self-parody, in which Tupac has a Keyser Soze–style epiphany while hearing the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Who Shot Ya?” for the first time in the prison yard and begins to connect the dots.

The choppiness makes a lot more sense when you’re aware of all the various fits and starts this project has gone through over the course of two decades. Directors have cycled in and out, including Tupac’s Poetic Justice director John Singleton, who angrily departed the project under disputed circumstances. Singleton is an uneven filmmaker, but he undoubtedly could’ve made, at the very least, a more competent film than what we have here. Instead, All Eyez on Me is left with Benny Boom, a director who is best known for making music videos, and three credited screenwriters who have little on their résumés beyond video games and one episode of Empire.

To the filmmakers’ credit, they don’t ignore any of Tupac’s biggest controversies. The Marin City incident, in which a fight Shakur was involved in led to the accidental shooting death of a 6-year-old bystander with a gun registered to him, as well as the sexual assault conviction, are just a couple of legal issues that get some screen time. That said, the way in which the latter event is handled is sketchy at best, with the film suggesting that the woman’s accusations are driven by vindictive motives. (After the judge finds him guilty of “unwanted touching,” she gives him a smug, pointed look from across the courtroom.) And the script is unafraid to acknowledge the many contradictions that arose from the same guy who wrote both the inspirational “Keep Ya Head Up” and “Hit ’Em Up,” his savage, misogynistic diss track, recorded at the height of the East Coast–West Coast feud, in which he claimed to have slept with Biggie’s wife, Faith Evans. Of course, it also chews on this concept in the most unimaginative of ways—as characters frequently ask him how someone so bright could be so drawn to negative people and actions. The Interviewer actually calls him a “walking contradiction.”

What about Shipp, the star, the man at the center of it all? Shipp may have been born with the look, but looking like Tupac is not the same as acting like Tupac—or for that matter, acting at all. The newcomer has a hard time inhabiting the fiery passion and swagger that made the original incarnation so electrifying. While he does a decent job of channeling the rapper’s spoken cadence, his eyes appear vacant throughout most of the film, making his characterization come across as hollow as that hologram.

The last 20 minutes or so of the film try desperately to create drama out of an ending we all already know, milking every moment for maximum ominousness. (“I’ll holler at him when he comes back from Vegas,” says an actor playing Snoop Dogg who looks nothing like Snoop Dogg but does sound just like him. “He’ll be all right.”) By the time you’ve made it to that protracted final scene, in which Shakur is laid out on the ground after having been shot by unknown assailants on the Vegas strip, as a gospel tune blares and an overhead camera shot reveals white smoke (or are they heavenly clouds?) passing over him, you’ll be surprised that All Eyez on Me showed enough restraint to not leave his arms spread out like Jesus.