To live without seeing the films of the Indian director Satyajit Ray, said Akira Kurosawa in 1975, “means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.” Though Ray was 11 years his junior, Kurosawa spoke of him that day in Moscow as a master. “I can never forget the excitement in my mind after seeing it,” he recalled of Ray’s debut Pather Panchali, 20 years after that film’s success at Cannes helped to usher in a new era of cinematic globalism—one that would eventually make it possible for a Japanese filmmaker to praise an Indian one in a speech being translated for a Russian audience. “It is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity and nobility of a big river.”

In 2015—now 60 years since Pather Panchali’s release—Kurosawa’s simple words remain the best Ray criticism I’ve heard and, really, all the recommendation his films require. Pather Panchali, along with its two sequels, Aparajito (1956) and The World of Apu (1959)—the three together are known as “the Apu Trilogy,” after their main character—has just been re-released by Janus Films in a pristine 4K restoration, to be made available in a Criterion Blu-ray set later this year. (The original negatives of all three films were burned in a film-lab fire in London in 1993, making the restoration process especially difficult.) If this trilogy comes anywhere near your town—it opened earlier this month for a run at New York’s Film Forum, with plans to spread to more U.S. cities through the summer—I can’t exhort you any more strongly to see it than Kurosawa already has. Do you really want to exist in the world without ever seeing the sun or the moon?

Those analogies from nature—celestial bodies, a flowing river—are especially apt for the first film, Pather Panchali (the title translates as “song of the little road”), which takes place in a forested region of Bengal remote enough that even a glimpse of a passing train is a daylong hike away. The Roy family—the impecunious Brahmin scholar and would-be writer Harihar (Kanu Banerjee), his more practical wife Sarbajaya (Karuna Banerjee), and their mischievous daughter Durga (Shampa “Runki” Banerjee as a child, Uma Das Gupta as a teenager)—once owned an orchard but were forced to sell it out of financial need. Now, to Sarbajaya’s lasting shame, they must listen to the neighbor family who bought the land from them accuse their daughter of theft. Durga does steal a guava or two every now and then, usually to give as a gift to the beloved old woman she calls “Auntie” (the toothless and bent-backed Chunibala Devi—unlike most of the film’s cast, a professional actress whose stage and screen career dates back to India’s silent film days). As the recurring spats between Sarbajaya and Auntie make plain, the old lady is a homeless mendicant who moves from family to family, depending for survival on her neighbors’ mercy and her own skills at manipulation. When a son is born to the Roy family, Auntie helps pitch in with the hammock swinging and lullaby singing. The baby soon grows into our observant and high-spirited hero, Apu (played as a child by Subir Banerjee), who’s first glimpsed only as a single wide, dark eye, peering at us in close-up from beneath a blanket.

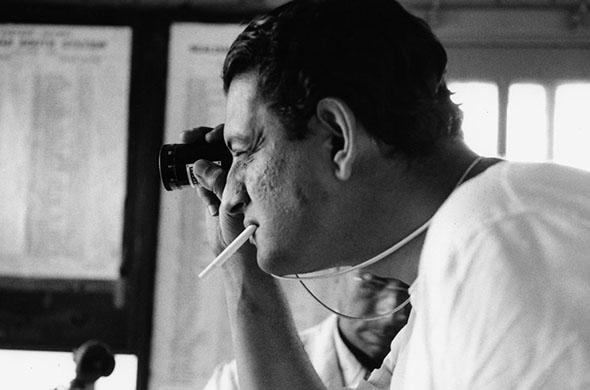

Photo by Marc Riboud/Magnum Photos/Janus Films

There’s nothing happenstance about the framing of that shot, or indeed, about anything Ray does with his nimble but modest camera. (The richly detailed black-and-white cinematography of all three films is by Subrata Mitra, who was only 21 when he began shooting Pather Panchali and had never before operated a movie camera.) By delaying Apu’s entry into the story for more than 20 minutes—and then introducing him with that one bright, screen-filling eye—Ray has first created a geographical, social, and familial context into which his protagonist will be born, then introduced into that world a new subjectivity that will become a proxy for the audience’s own. From behind those eyes we will experience not only the growth to adulthood of one man, but the development of a young and troubled nation.

India had just declared its independence from English rule in 1947, in the same partition of colonial territory that had split Ray’s native region of Bengal into two parts, the Hindu western half belonging to India and the Muslim east to Pakistan. (One bloody revolutionary war later, East Bengal would become its own nation, Bangladesh.) The sutures of that historical wound still feel fresh in the Apu trilogy, which widens in geographic and political scope as it moves from the rural setting of Pather Panchali to the holy city of Benares (now called Varanasi) in Aparajito and finally, in The World of Apu, to the more cosmopolitan and capitalist milieu of Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), where the grown-up Apu moves to make his way. The trilogy is based on two novels by the Bengali novelist Bibhutibhusan Banerjee, and Ray’s regional and linguistic nationalism is always palpable without ever becoming explicit—it’s there, for example, in the lilting Bengali poetry Apu recites aloud on several occasions, first as a precocious schoolchild and years later as a young scholar drunk on the love of language (and liquor).

My editor assured me that 60 years was enough time passed not to have to worry about “spoiling” the Apu Trilogy. But I still can’t bring myself to reveal much about the series’ twists and turns, because most of their pleasure and surprise come in the way Ray allows everyday life—with its daily disappointments, sudden tragedies and unplanned-for moments of delight—to unfold at a natural, unhurried pace, as if the movie itself were something that grew up out of the ground. “Auntie” is repeatedly kicked out of the Roys’ household for her mooching ways, only to shuffle back a few days later with her bundle of clothes in hand and toothless grin intact. The father disappears to the city for months to find work, leaving his anxious wife to hold the family together through a period of sickness and financial hardship. (In an era when the domestic experience of women was seldom the focus of films made in the West, Ray put Apu’s mother at the emotional center of Pather Panchali, and Karuna Banerjee’s quiet, anguished performance evokes some of the great actresses of melodrama: Lillian Gish, Ingrid Bergman, Anna Magnani.) The sequence in which Apu and his sister Durga set out for a long walk while monsoon season is approaching, pausing (along with the camera) to witness the delicate skimming of water bugs across the surface of a pond, brings to mind one of those moments in Hayao Miyazaki’s animated films when all human activity stops short to attend to the movement of nature. In these movies, time passes in a way that feels real—an effect that inspired generations of filmmakers even if, like Ray fans Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, and Wes Anderson, they made very different movies from his.

Courtesy of Janus Films

In the second film of the trilogy, Aparajito, the adolescent Apu—played by two actors, first Pinaki Sengupta and later Smaran Ghosal—has become a promising student in Benares, where his father has found regular work as a lay Brahmin priest. Apu, still as wide-eyed and curious as when he first peeked out from that blanket, has begun to get a sense of the larger world outside his limited experience—a discovery symbolized by the small globe he carries around like a talisman. But a terrible loss forces the family to move yet again, and by the film’s end Apu has gone on his own to Calcutta to pursue his studies.

In The World of Apu our hero, now played by Soumitra Chatterjee, is a penniless but passionate young man in his 20s, selling off books of English poetry to pay the rent on his one-room Calcutta flat while he works on an autobiographical novel. Through a turn of events that’s at once comic and horrifying, Apu finds himself in an arranged marriage to a young girl, Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), whom he barely knows and who knows even less about him. But gradually the two strangers begin to fall in love—a development signaled by a simple and wonderful transition in which the movement of a straw hand fan, wielded first by Aparna and then by Apu, signals both the passage of time and the growth of their shared affection.

By the end of the third film, Apu has become such a full and complex being in the audience’s imagination that we see the whole story of his past—his loves, his losses, his unfixable mistakes—reflected in the face of Soumitra Chatterjee (who was a professional actor at the time Ray cast him, and who would go on to become one of the director’s most faithful collaborators). The watchful boy of Pather Panchali, looking out from under that blanket, has become the pensive man of The World of Apu, and there’s a direct, but never overemphasized, line of continuity between the 6-year-old wild with excitement about the rare arrival of a letter and the nearly 30-year-old scolded at work for mooning over a packet of love notes.

The exquisite musical scores for all three films are by the sitar master Ravi Shankar—not yet a crossover success in the West in those pre-Beatles days but enough of a star on the Indian concert circuit that he only had time to record the first two soundtracks by improvising over the course of a single viewing. This gives those films’ musical backdrop the freshness of an improvised jazz score, like the one Miles Davis would record a few years later for Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows. The World of Apu has a fuller, more orchestrated soundtrack, which matches well with the increasing ambition and amplitude of Ray’s cinematic technique. In between making the second and third films in the series, Ray had directed another, his 1958 masterpiece The Music Room, and the growth of his confidence as a filmmaker is evident alongside the development of his sensitive hero.

The Apu Trilogy is often spoken of in terms of its debt to Italian neorealism—a style that certainly influenced Ray after he viewed Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (and, by his own count, 98 other films) during the three months he spent in London in 1950 working for an English advertising agency. But the Apu films have a lyricism, at times even an aching romanticism, that’s absent from the neorealists’ proletarian chronicles of postwar subsistence. In the space between tragic losses—at least one of which occurs in every film—and fleeting moments of intimacy and joy, there’s always time to stop and watch the water-skimmers, to hear a snatch of birdsong in the forest, or to declaim a few tipsy lines of verse to a friend as the two of you walk home along the train tracks after a night out. It’s these interstitial scenes that weave the events of Apu’s life into the viewer’s own memory, and stay with you—take my word on this one—through decades of your own such fleeting moments.

In that same 1975 speech, Kurosawa marveled at the plenitude of the cinematic minicosmos Ray created in the Apu Trilogy: “People are born, live out their lives, and accept their deaths.” Don’t accept yours until you’ve seen these sublime restorations of the Apu movies on the big screen.