While We’re Young, the new movie from director Noah Baumbach, begins with a few lines from Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder. Ibsen’s aging character Solness wonders if he should “open the door” to the younger generation, fretting that they might “break in upon me” and seek “retribution.” Roughly 90 minutes later, as the movie’s end credits roll, we hear the gentle strains of Paul McCartney’s “Let ’Em In”: “Someone’s knockin’ at the door / Somebody’s ringin’ the bell / Do me a favor, open the door and let ‘em in.” In the space between, two Gen Xers get their doors kicked down by a pair of millennial younguns.

This isn’t the first time Baumbach’s offered a cinematic snapshot of life-stage anxiety. Kicking and Screaming centers on that fraught moment at the close of college when aimlessness melds with the terror of exiting childhood’s cocoon. Frances Ha captures the transition from young adult to just plain adult—that sobering process in which ambitions get rudely re-aligned to circumstance. Now comes While We’re Young, which is—from its on-the-nose title, to its portentous Ibsen reference, to its soundtrack’s repeated use of David Bowie’s “Golden Years”— Baumbach’s most explicit look yet at one of life’s angsty microphases.

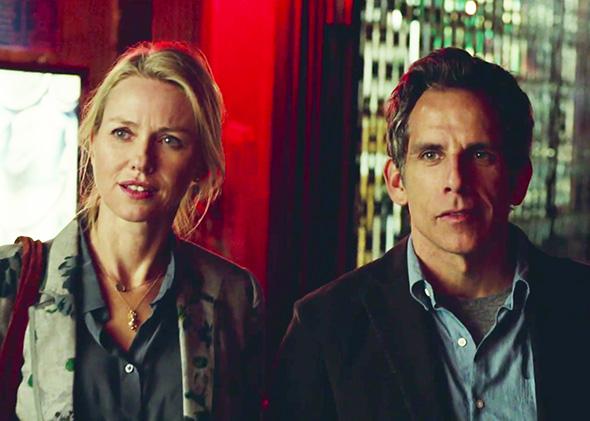

Fortysomethings Josh (Ben Stiller) and Cornelia (Naomi Watts) are childless and bored, unsure what’s left to do before death, when they serendipitously find a twentysomething couple (played by Adam Driver and Amanda Seyfried) to hang out with and borrow some pep from. All goes smoothly at first. Later, it becomes unclear who’s borrowing what from whom.

I ♥ Noah Baumbach, and found plenty of classic Baumbachian slyness to love in While We’re Young. If you’re like me, you’ll chuckle at the metajoke that casts Beastie Boy Ad-Rock, the coolest Gen Xer of all, as a dorky dad with a herniated disk. And you’ll encounter no shortage of shiny, angular dialogue: Seyfried’s character initiates a date by asking, “You wanna get some goat?” and later wearily proclaims, “If I stay here any longer I’ll girl interrupt.”

This is, however, easily Baumbach’s broadest film. It features a dopey drug sequence in which vomiting gets played for laughs, and a “douchebag” shaman administers ayahuasca before bragging about his yacht. The entire scene might just as well have shown up in an assembly-line Vince Vaughn comedy. The film’s third-act plot turns are way tidier, way more Hollywood, than we’ve been trained to expect from Baumbach’s previous New New Wave oeuvre. At one point, character development is signified by Ben Stiller stuffing a recently acquired trilby into a garbage can—a worn-out midlife crisis gag that also shows up in a Lowe’s advertisement getting heavy rotation during NCAA tournament games.

As a Baumbach maniach, I adored this film and hope others will, too. But there’s no doubt that While We’re Young plays like an attempt to appeal to the (slightly) baser instincts of a (slightly) wider audience. Stiller’s character is a 44-year-old filmmaker, a “purist” who’s won critical acclaim from some quarters but has a “fucked-up relationship with success”—in that he’d like a whole lot more of it. Baumbach is a 45-year-old filmmaker who’s created a string of gimlet-eyed little movies that delight people like me but that might not be quite the collective triumph (in terms of either top-shelf artistic recognition or wild box office success) that I would guess he envisioned for himself back when he directed his first film at 26.

While We’re Young ends on an up note, but it’s a forced one. At its core this movie is a meditation on the bitterness of middle age, when we inevitably begin to both revere and resent youth. Stiller’s character evinces the small-c conservatism that nearly always accompanies our advancing years. He scoffs at the next generation’s slipping ethical standards and lack of discernment—at one point complaining that they can’t distinguish between The Goonies and Citizen Kane. “Different things matter now,” he’s gently told. That gives him no solace.

In a 2013 New Yorker profile, Ian Parker posited that Baumbach’s burden over much of his career has been “ruefully noting that, in the nineteen-seventies, someone who had made work like this might have had a reputation as a mainstream director.” He quotes Baumbach describing his own fucked-up relationship with success, through the lens of Baumbach’s attitude toward the viewers of his films: “Probably, at some level, I’m not quite letting you laugh, and then getting annoyed when I don’t get the laugh.” In 2012, Baumbach shot a big-budget, high-profile pilot for HBO, attempting to adapt Jonathan Franzen’s book The Corrections into a prestige series starring Ewan McGregor and Chris Cooper. It was the biggest project he’d ever taken on. It was not picked up.

You can feel Baumbach striving for a departure here, the next step in the accessible career The Corrections might have made for him. And he succeeds in some ways. While We’re Young is an odd combination: It’s a parable about a director coming to grips with his telos—made by a director hoping to swerve toward a new telos. But look closely at his characters and you’ll see that, no matter what sorts of contexts this auteur creates for them, no matter how rosy their denouements, they all end up linking smoothly into an unbroken chain of protagonists who are self-absorbed, self-flagellating, and profoundly disappointed.