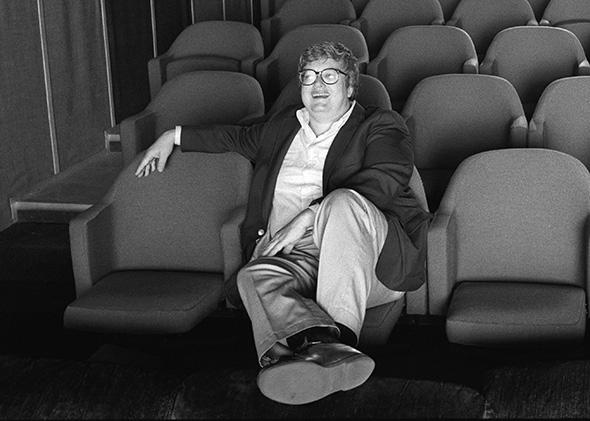

Life Itself, the affectionate, candid, sometimes tough-to-watch tribute to Roger Ebert from the great documentarian Steve James (Hoop Dreams, The Interrupters) fans out a deck of contradictory snapshots of this vibrant and complicated 70-year-long life—a life that came to an end in April 2013, just five months after James and Ebert first sat down to collaborate on a plan for the film. Using archival photographs, TV and movie clips, and talking-head reminiscences, James shows us Ebert the cherubic altar boy, the precocious teenage journalist, the hard-drinking Chicago Sun-Times newspaperman, the arrogant onscreen sparring partner of lifelong frenemy Gene Siskel, the prolific Web entrepreneur and late-life Twitter phenomenon, the indomitable cancer survivor, the devoted husband and stepfather, and the tireless mentor and champion to both filmmakers and younger critics (including the preteen version of this one).

Long portions of the documentary are accompanied by voice-over narration from the 2011 memoir from which the film takes its name. But anyone who’s read that memoir—or is familiar with the story of the critic’s last eight years, during which a series of operations for thyroid cancer deprived him of most of his lower jaw as well as his ability to eat, drink, or speak—will find herself puzzling over the fact that these vivid reminiscences are coming to us in the voice of a man who, at the time those words were written, no longer had a voice at all. In fact, the narrator is Stephen Stanton, a vocal impressionist who’s an expert at “voice-matching,” and who captures Ebert’s familiar Midwestern cadences with uncanny accuracy. Finding Stanton was a major coup on James’ part. His incarnation of the critic is more than an impersonation; it’s a true performance, and it leaves the audience with the eerie feeling that Ebert has somehow come back to life long enough to tell his own story.

To characterize that story as “colorful” is an understatement as outsized as the man himself. At the Daily Illini, the college newspaper where he served as editor during his years at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Ebert wrote astonishingly mature editorials in support of the civil rights movement and once literally stopped the presses to keep a tasteless ad from running opposite the news of JFK’s assassination. As the youngest film critic in the country (a job he was handed without applying for it after five months as a reporter at the Sun-Times), he quickly became a regular at Chicago watering holes known for their shady clientele.

Ebert frankly describes his younger self as “tactless, egotistical, merciless and a showboat”; he was also a raconteur, a womanizer, and an alcoholic (though he never took a drink again after going sober in 1979). He wrote the script for Russ Meyers’ tawdry 1970 boobs-and-babes epic Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and helped Martin Scorsese emerge from a dark period of cocaine addiction by hosting a festival retrospective of his films (a story Scorsese, who was an executive producer on Life Itself, recounts with tears in his eyes). Ebert remained loyal to Chicago, and the working-class readership of the Sun-Times, for five straight decades, even after he won a Pulitzer in 1975 and was aggressively courted by every paper in the country. In that same year, he began the collaboration with Gene Siskel that would make these two untelegenic Chicagoans into the most unlikely media stars of their time.

“Roger was not just the chief character and star of the movie that was his life, he was also the director,” observes Ebert’s lifelong friend Bill Nack. Ebert’s directorial tendencies are on display during his occasional onscreen interactions with James. In one early scene, Ebert offers James some mise-en-scène tips from his hospital bed: “Steve, shoot yourself in the mirror,” he instructs through a computerized voice synthesizer, in a gesture of inclusion that’s at once generous and micromanaging. James doesn’t flinch from showing us some of the harsher aspects of Ebert’s medical treatment, including the unlovely reality of the flushing out of a feeding tube. It starts to feel as if we’re invading a frail old man’s personal privacy—until we see Ebert telling James (via email) that he’s glad the director is including these scenes: “I’m happy we got a great thing that no one ever sees: Suction.”

The heart of Life Itself, and the part of the film that’s most instructive even for those familiar with Ebert’s story, is the long middle section dealing with his stormy, never-resolved relationship with Gene Siskel, who starred with him in various incarnations of their televised movie-debate show from 1975 until Siskel’s sudden death of brain cancer in 1999. Interviews with the show’s producer and with Siskel’s wife, Marlene, point up the characterological divide between the two men. Siskel was a cosmopolitan philosophy major who became part of Hugh Hefner’s inner circle (cue some magnificent archival photos of Siskel ogling topless vixens while sporting a walrus mustache). Ebert’s taste was earthier and more populist. Their decadeslong collaboration was both fiercely competitive and profoundly interdependent, a complex and inextricable knot of enmity and love. I won’t spoil some of the film’s best moments by describing the many hilariously testy Siskel/Ebert outtakes, in which the two critics jockey for better camera positions and mock each other’s flubs. Let’s just say that Time magazine critic Richard Corliss (who once wrote a diatribe against At the Movies’ dumbing down of film culture, and who’s interviewed here) isn’t wrong when he describes the show’s basic appeal as that of “a sitcom about two guys who lived in a movie theater.”

“Back in the old days, Roger had the worst taste in women of probably any man I’ve ever known,” recalls a bartender who was Ebert’s buddy during his drinking years. “They were either gold diggers, opportunists, or psychos.” That all changed when Ebert met his wife of 20 years, Chaz, at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting (a fact she reveals for the first time in an interview here). James warmly depicts the couple’s mutual devotion and Chaz’s unwavering support, but he doesn’t gloss over a few snappish exchanges during Ebert’s painful transition from the rehab facility to their home, where he would spend his final days.

Life Itself has a few notable lacunae, moments when James’ evident love and respect for his subject shade into selective amnesia. Though there’s an illuminating interview with one of Ebert’s handpicked At the Movies successors, Times critic A.O. Scott, the critic Richard Roeper, who co-hosted the program with Ebert for eight years following Siskel’s death, goes entirely unmentioned, as does Scott’s partner on the show, the Chicago Tribune’s Michael Phillips. And though the film touches briefly on Ebert’s support for young, independent filmmakers, including Ramin Bahrani and Ava DuVernay (who both offer moving testimonials here), I would have loved to see more about Ebert’s late-life fostering of young critical talents around the world, including the Far-Flung Correspondents he invited to write for his site and visit the annual Ebertfest film festival in his hometown. Out of all the personae Ebert assumed during his long and well-lived life, this is the way many of us whose lives he changed will remember him best: as a born teacher, not just about the movies but about resilience, compassion, joy—life itself.