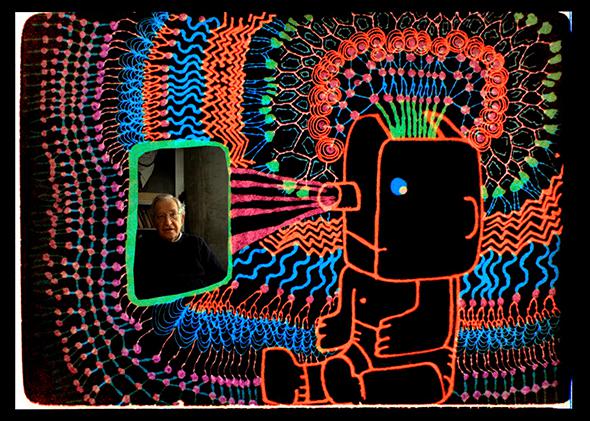

Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?, the French director Michel Gondry’s animated documentary about the linguist, philosopher, and left-wing activist Noam Chomsky, seems at first like it’s going to be dragged down by an excess of whimsy. As he queries the 84-year-old M.I.T. professor about everything from his groundbreaking work in childhood language acquisition to his views on religion, astrology, and life after death, Gondry deals with the eternal talking-head-interview quandary—what am I going to show on screen besides a boring stationary shot of my interesting subject’s face?—by hand-illustrating Chomsky’s ideas as the philosopher explains them. Gondry has a delightful drawing style, childlike but elegant, with figures that morph playfully into other shapes or break up and skitter across the screen as letters. Intermittently we’ll get a shot of Chomsky’s face as he talks—sometimes seen on an animated movie screen, or otherwise embedded in the drawn image. In the background, if we listen, we can hear the faint clicking sound of the 16mm camera Gondry used to shoot his two long interviews with Chomsky. Occasionally, we even see Gondry at his home animation station (which is not a computer but an old-fashioned Oxberry animation stand) laboriously photographing one drawing after another. If we are to take this film’s autobiographical metanarrative at its word, Gondry’s filmmaking process was DIY to the point of near-insanity.

I have a feeling I’ve lost a few of you already with all this talk of whimsy and DIY and autobiographical metanarrative. But if you’re at all interested in either Chomsky or Gondry—or better yet, if you’ve never heard of either but are just interested in language and meaning and life— please give Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? a chance to win you over. Once you get used to its basic concept—listening to one very smart man talk while another very creative man draws his impressions of those words—this deceptively slight documentary starts to transform into a kind of meditative experience. You can scrutinize the drawings for all the little details and visual puns—or you can just let them entertain your eyes while you listen. More than anything, Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?—a clumsy title that comes from an example Chomsky gives during a conversation about generative grammar—feels like taking a master class with an eminently wise and generous teacher while sitting next to a guy who’s a really, really good doodler.

Among the subjects Chomsky tackles, if anyone so retiring and soft-spoken can be said to “tackle” anything: his notion of an inborn, universal human grammar, which, though it’s still hotly debated decades later, changed the field of linguistics forever; his disgust at Europe’s treatment of the Roma people, which he says amounts to waging a second Holocaust on a people that has already survived one; and his fondly remembered childhood in Philadelphia, where he learned his first foreign language at the elbow of his father, a Hebrew scholar committed to keeping the then-endangered language alive. There’s a lovely moment when Gondry’s drawings work against the grain of Chomsky’s words, briefly exposing the emotion beneath them. When the professor refuses, politely but flatly, to discuss his feelings about the death of his wife of 59 years (the Harvard linguist Carol Chomsky), Gondry gives us an extended animation of a young man and woman riding bikes together. The only sound in the background is music and that whirring camera. The image might be sentimental if it were accompanied by Chomsky’s warm reminiscences of his beloved; against the backdrop of his silence, it’s perfect.

Gondry’s The Science of Sleep was all about a young man (Gael Garcia Bernal) foundering in the depths of his own creativity, a hypersensitive fantasist unable to connect with other people or hold down a real-world job. Gondry channels that character at times during these interviews, especially when he displays, sometimes too stagily, his flustered awkwardness in the presence of this man he so obviously regards as a sage. At other times, Gondry details, in a heavily French-accented voiceover, his doubts about the viability of the very project we’re watching—a self-aware artistic gambit that can get airless pretty fast. And the dreamily apolitical Gondry seems less at home when Chomsky moves from pondering the origin of language to discussing the human-rights and environmental work that’s occupied much of his late career. But when his pen is grooving in sync with Chomsky’s mind—which is the case for the vast majority of this odd but irresistible movie—Gondry’s in as good a place as a filmmaker as he’s been since his 2004 masterpiece, the Charlie Kaufman collaboration Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, another project that involved one man’s visual imagination spinning magic from another man’s words.