The Nebraska of Nebraska is a lot of places at once. It’s a geographical location, of course—the Cornhusker State, home to the film’s director, Alexander Payne (though he grew up in Omaha, far from the rural back roads where most of the story takes place), as well as the birthplace of Nebraska’s Woodrow T. Grant (Bruce Dern). It’s also the final destination of the multistate road trip that Woody and his son David (Will Forte) make from their adopted hometown of Billings, Mont. But to the septuagenarian Woody, a former auto mechanic and lifelong alcoholic whose dementia is beginning to interfere with his everyday functioning, Nebraska also represents a kind of oasis on the plains, a place of impossible fulfillment: It’s there, he believes, that he will collect on the sweepstakes ticket that makes him a millionaire.

The sweepstakes, unsurprisingly, is the most transparent of scams, the kind of mass-mailed magazine promotion that Ed McMahon would have lent his auto-signature to back in the day. But Woody’s delusional belief in his own stroke of fortune is such that his plain-spoken wife, Kate (the very funny June Squibb), can’t keep him from setting out—on foot—to make the 850-mile journey to pick up his reward in Lincoln. Unable to control the wandering of her increasingly senile husband, Kate calls their younger son at all hours to drive around in search of him. David’s older brother Ross (Bob Odenkirk), a local TV anchor with a wife and kids, is too busy to check in as often with his parents, but David, a struggling stereo equipment salesman whose girlfriend has just left him, has plenty of time on his hands. Eventually, sick of cruising the streets of Billings searching for his bitter and monosyllabic father (who, as Ross points out, was never a decent parent to begin with), David agrees to drive Woody to Lincoln by the sweepstakes deadline. His motivations seem to lie somewhere between the filial—it’s an opportunity to get some quality time with his ever more checked-out dad—and the vengeful: It’s a chance to prove to the selfish old coot that he didn’t win jack.

If you think that sounds like the setup for a heartwarming intergenerational road movie, you must not know Alexander Payne very well. Filmed in stark, un-nostalgic black and white in the cold of a Great Plains autumn, Nebraska (which was written by Bob Nelson) isn’t without heart—it’s far less emotionally chilly, for example, than the work of Payne’s fellow Midwestern satirists the Coen brothers—but it takes time and patience to get to this movie’s (marginally) gooey center.

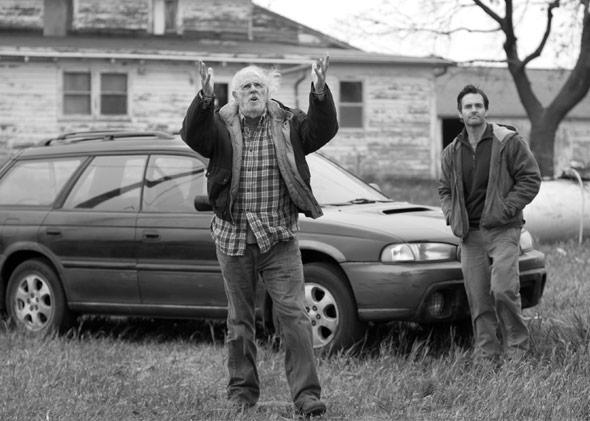

Dern’s Woody isn’t glamorously wicked enough to be called an antihero. He’s an even harder character type to like: an angry, self-pitying, slightly pathetic drunk who rebuffs his son’s attempts at bonding with either cranky putdowns or dismissive grunts. But as played by the 77-year-old Bruce Dern (in a near-mute but magnificent performance that, like the movie, unfolds its layers slowly), Woody is so unpredictable, complicated, fragile, and real—so human—that we can’t help but care about him even at the moments when we dislike him intensely. That emotional dissonance seems fitting in a movie about trying to love the family you have, not the one you would have wanted. Dern’s quiet, deeply internal performance requires a sensitive co-star to bounce off of, and Forte—whom you may remember with a stalk of celery up his butt in the goofy SNL-spinoff comedy MacGruber—turns David into far more than just a beleaguered, eye-rolling straight man. You see how his anger at his father is bound up with his determination to somehow find a way in to the old man’s remote, inaccessible heart.

Barely speaking, father and son make their way across Wyoming and South Dakota, with a side trip to Mount Rushmore. (“A bunch of rocks,” shrugs an unimpressed Woody.) Their road trip unrolls in a leisurely fashion—lots of shots of gas stations, snowy plains, and grazing bison—but with stunning black-and-white cinematography by Phedon Papamichael and a wistful fiddle score by Mark Orton, its contemplative pace feels just right. Eventually David and Woody make it to the small town of Hawthorne, Neb., where Woody grew up. There, they stop to spend the weekend at the house of one of his many equally taciturn brothers. (A shot of the Grant siblings watching TV looks like the male half of the American Gothic couple reproduced in quintuplicate). Making the rounds of the taverns on Hawthorne’s main street—can you say “rounds” if there are only two?—Woody can’t resist boasting about his sweepstakes win, and soon the whole town, including his former business partner Ed Pegram (Stacy Keach), believes that their seventysomething local boy has made good. The harder David (and his mother and brother, who have joined them in Hawthorne for an impromptu family reunion) try to set the record straight, the more convinced Pegram and the extended Grant family become that Woody is a millionaire, and that, having helped his sorry ass out in the past, they deserve a piece of the action.

The last third of the movie brings in a farcical element that Payne fans will recognize from his earlier films. (Remember Paul Giamatti and Thomas Haden Church’s slapstick mission to rescue a lost wedding ring in Sideways?) The increasingly importunate relatives, spearheaded by David’s hulking, dim-bulb cousins (Devin Ratray and Tim Driscoll), step up the pressure on Woody to fork over some of his nonexistent dough, even as Pegram rapidly escalates from congratulating his ex-partner to openly threatening him. Woody, Kate, and their sons go to a cemetery to pay less-than-respectful tribute to some deceased ancestors. “I liked Rose, but she was a whore,” insists Kate, before lifting her skirt over the grave of an old beau: “See what you could’ve had, Keith, if you hadn’t talked about wheat all the time?” And in the movie’s best comic set piece, the Grant boys (wonderfully played by Odenkirk and Forte, who really seem like brothers) try to steal back an air compressor that their father lent Pegram 40 years ago and never got back. I won’t reveal whether David and his dad ever make it to Lincoln, except to say that the final scene, which takes place on the by-now-familiar main street of Hawthorne, leaves the viewer both feeling both bottomlessly sad and oddly buoyant.

There are viewers who will find the folksy humor of Nebraska’s comic scenes too broad, and others who will condemn Payne’s portrayal of Midwesterners as caricatured and condescending. I am not among those viewers: I’ve always admired this director’s commitment to both seriousness and laughter, to showing the beauty and significance of ordinary human life side by side with its petty, venal absurdity. Nebraska’s unsentimental but ultimately loving vision of small-town America seems closer than ever to Preston Sturges’—a director to whom Payne is often compared, and whose great satire Hail the Conquering Hero (about a hapless soldier who’s mistaken for a war hero without ever having fought a day in his life) seems like a clear influence here. But a long, nearly silent scene in which Woody and his family visit the empty hulk of the house where he grew up, or another in which his high school sweetheart (Angela McEwan) catches a glimpse of her old beau for the first time in 40 years, aim for something very different from Sturges-style satire. There’s something almost Lear-like about Woody in those late scenes, surveying the void of his past with eyes that have seen too much. He’s halfway gone from the world already, en route to his own private Nebraska.