On Aug. 25, I noticed a smattering of social-media elegies for Neil Armstrong. Mournful moonwalk jokes. Heartfelt hashtags. The only problem was that Armstrong has already been dead a year. Posts commemorating the first anniversary of his passing had been misconstrued as breaking news. This cultural blind spot brought to mind Tom Wolfe’s biting New York Times editorial “One Giant Leap to Nowhere” from 2009, in which he lamented NASA’s diminished status in our daily lives: “If anyone had told me in July 1969 that the sound of Neil Armstrong’s small step plus mankind’s big one was the shuffle of pallbearers at graveside, I would have averted my eyes and shaken my head in pity. Poor guy’s bucket’s got a hole in it.” House Republicans seem eager to let that bucket continue to drain, having barely mentioned the defunding of NASA among the casualties of their government shutdown.

I don’t believe all Americans are completely disengaged from the space program, but we’ve clearly reached a point where the next giant leap most readers are likely to take is checking out a frog photobombing a NASA launch. (That picture is nuts.) Before taking a licking, Kepler, NASA’s planet-hunting spacecraft, discovered potentially habitable planets in the “Goldilocks” zone, and yet somehow a report on floating clouds of dead skin trapped inside the International Space Station is just as mesmerizing. And as new data pours in from Mars—or at least did before the Curiosity rover was furloughed—are we more concerned that Curiosity has failed to find methane (indicating no signs of life), succeeded in finding traces of water (possible life?), or that one of its flight directors has a photogenic Mohawk? Maybe it’s us who need lives.

The state of serious sci-fi cinema has lately been just as suspect. We’ve drifted far from H.G. Wells, HAL-9000, and John Glenn swatting fireflies in The Right Stuff. Where are the heavyweight productions that awaken audiences to the infinite possibilities of space? One where special effects hit our subconscious, not just our wallets for premium tickets?

After a considerable drought, the gifted director Alfonso Cuarón, reunited with Emmanuel Lubezki, arguably the best cinematographer at work anywhere in the world today, has finally provided audiences with a complex character study disguised as a traditional shipwreck thriller. Gravity hits theaters this week, riding a comet tail of critical praise and festival raves. James Cameron declared it the “best space film ever done” and commended its human dimension and technical mastery in equal measure. The film opens with a stunning, unbroken shot of a routine spacewalk—or extra-vehicular activity (EVA)—before a swarm of debris cuts everything in its path to ribbons. To make matters worse, because our protagonists are trapped in orbit, the swarm is constantly coming back around the bend—a sunrise with teeth. I won’t spoil any plot points here, but needless to say, the special effects and performances are sensational, and the pace is relentless.

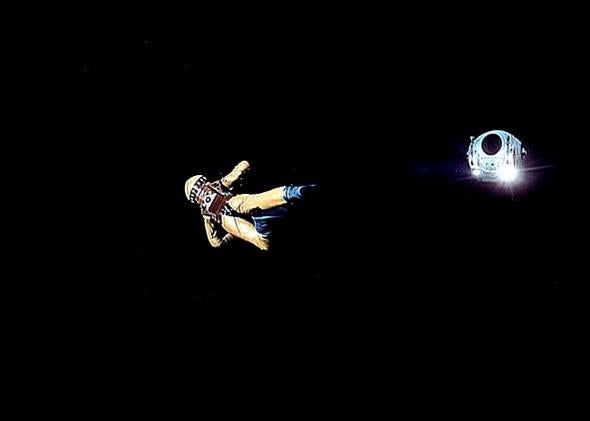

Storytellers have been fascinated with what could go wrong in space long before mankind had the technology to even leave the atmosphere, and we’ve arrived at a moment where cinematic tools have finally caught up to our imaginations. What Cuarón offers is a sense of grace and psychological depth that makes him, in my view, the first 21st century commercial filmmaker to stand alongside the visionaries of the printed word like Stanislaw Lem or Ray Bradbury. The moment the Gravity teaser trailer splashed across the Internet, several commenters were reminded of the classic Bradbury short story “Kaleidoscope,” published in 1949, in which a rocket splits apart and the crewmates scatter into the dark sea like a “dozen wriggling silverfish” until the poetic climax of the story, when a small farm boy in Illinois mistakes one of the bodies re-entering the atmosphere for a falling star.

While Bradbury contemplated the boundless terror of spiraling helplessly through the darkness, few films have been able to truly enter the minds of those in peril. Before Gravity eclipsed it, Europa Report, an ambitious “found footage” film released earlier this year, was perhaps as close as it got. An astronaut whose suit is contaminated during a spacewalk is forbidden re-entry and must abandon ship, using the extra me-time to sign off to his crew and family back on Earth. The camera affixed inside his helmet catches his final gasps in a serious case of personal-space invasion. The scene feels eerily authentic, thanks to the performance of Sharlto Copley, last seen 3-D–printing his own face in Elysium.

The beleaguered protagonists in Gravity occasionally use humor as a coping mechanism—a wise choice by Cuarón, to provide the exhausted audience a few scavenged moments to recalibrate. The tactic is wielded most expertly by Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), whose cowboy bravado and occasional zingers help calm his less qualified compatriot, Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), through the madness. During these pockets of levity, I was reminded of the strain of dark humor that courses through other depictions of space tragedies. In Dark Star, for example, John Carpenter played a deadly spacewalk for laughs, when the stranded (and aptly named) Lt. Doolittle surfs a hunk of space debris to the tune of “Benson, Arizona” before being bug-zapped by a mystery planet’s atmosphere. Other times, the laughter is unintentional, as with the cosmically corny Destination Moon (1950) and its whiz-bang dialogue. “Wow!” says an upturned spacewalker, gazing down at Earth. “Geography books are right!”

Clooney’s Kowalski may also have the most refined reality-distortion field ever depicted in cinema. If the sight of the International Space Station suffering more dents than the shark tank in Jaws doesn’t faze you, nothing will. But is it possible this sense of calm and composure has shades of truth, and isn’t simply a caricature?

To find out more about the mentality of spacewalkers, I arranged to meet with retired NASA astronaut Story Musgrave, a veteran of six spaceflights and a designer of the spacesuits and life support systems used on spacewalks. Musgrave was a spacewalker on Challenger’s maiden voyage, as well as the first mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. A Florida resident and proud Kentuckian, he spends a week each month at Applied Minds, a research facility known as the “little Big Idea company,” located in the industrial outskirts of Glendale, Calif.

Though Musgrave is active in the press and is something of a go-to for on-camera interviews about the space program, being in his presence is still slightly ethereal. The same person I was now conversing with in a Glendale conference room had been in orbit in his 60s, California a mere peripheral speck. Musgrave prefaced his remarks by saying he lived an isolated childhood and didn’t see many movies, though he was more than eager to relay his experiences working as a space consultant on Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars (which features yet another spacewalk-gone-wrong; Tim Robbins goes butterfingers while lassoing a stray piece of equipment and coasts to his death, eyes glazed and body flambéed by the Red Planet).

I began our conversation by asking about a news item that had recently gone viral: Luca Parmitano, the first Italian spacewalker, had spoken publicly about feeling like a “goldfish in a fishbowl” when his helmet inexplicably filled with liquid during a routine EVA. The episode seemed to fulfill two primal nightmares—drowning and being lost in space—and was perhaps the most-discussed space-related news item this summer. I was surprised, though, when I read that this was the closest any spacewalk had come to catastrophe. “That’s true,” Musgrave said. “I’m massively, horribly proud of the spacewalking system. We’ve performed between 200 and 250 spacewalks with no problems.” Regardless of the sterling safety record, there must be some lingering sense of fear. “No fear at all,” Musgrave said with a mild shrug. “The statistics are heavily in your favor. Going out the door is simply performance; it’s an athletic event, a dance, pure choreography.” He stressed that the shuttle launch is by far the riskiest phase of any mission, a subject he didn’t take lightly, given the well-documented horrors of Challenger and Columbia—a subject filmmakers seem unwilling to touch.

Courtesy of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM)/Stanley Kubrick Productions

But if spacewalks are so safe, so routine, is it galling that almost every depiction in movies ends in a worst-case scenario? “Not at all,” he said. “People want drama. I have no problem with people wanting a dramatic story.” I figured it was okay, then, to inquire into his personal favorite. “Well, 2001 is the standard. Movies before it didn’t catch the archetypal. The thing is, how do you touch people down deep?” Though Stanley Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke—himself a spacewalker of sorts, now that his DNA will be sent into orbit around the sun—asked bold, penetrating questions about the nature of exploration that still mystify viewers, their plot also hinged significantly on a spacewalk catastrophe. For all the inventive ways Kubrick depicted death—a bull ride on an A-bomb, Nicholson axing clairvoyants—a neurotic computer detaching an astronaut’s air tube and sending him spiraling into nothingness remains, to me, his most chilling.

It was also a masterpiece of craft. I connected with David Larson, who shared details from his research on a long-gestating documentary on the making of 2001. Kubrick hired Eugene’s Flying Ballet, an English company specializing in wirework for film and theatrical productions, to execute this highflying sequence, with famed stuntman Bill Weston occupying the spacesuit of Dr. Poole, the victim of HAL’s short circuit. According to Larson:

Weston was hung from the top of Stage 4 at MGM-British Studio in Borehamwood on two thin wires, with the 65mm camera filming up at him, so his body hid the wires. He also had an O2 canister with an air tube running up through the suit to the helmet, which only lasted around 20 minutes. The signal was a ‘Jesus on the cross’ position when the O2 was running out. During one take, the scaffolding used as a jumping-off platform was taking a long time to move away, [which cut] into the filming time. As Weston did the “Jesus” signal, Kubrick said, “Leave him up there, we just started.” Weston passed out and was lowered to the floor and revived. He told me in my interview with him that he went looking for Kubrick to “have at him,” but couldn’t find him. The next day his trailer had a bottle of wine in it and his pay was raised, so he forgot about the incident.

Bottoms up! As a kid, I distinctly recall being tweaked by the high-wire recreation of the spacewalk from the film’s sequel, 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984), as part of the Universal Studios back lot tour. Two audience members were handpicked and suited up to pantomime the scene in 2010 where two astronauts float from a Russian ship to the original (and now abandoned) Discovery, which, coincidentally, had to be built from scratch, as Kubrick had ordered all of his 2001 models to be destroyed after filming, precisely to avoid this kind of thing.* (In a movie sequel that is the cinematic equivalent of Geraldo unearthing a few empty gin bottles in Al Capone’s vault, I contend that this spacewalk scene is pretty fetching.) The sound of John Lithgow hyperventilating was soon pumped into the Showcase Theater, and my 5-year-old mind couldn’t quite comprehend the prospect of dangling in space, Jupiter throbbing beneath your toes, regardless of the fact that this was merely a blue-screen shadow play off the 101 Freeway.

Throughout Gravity, I experienced that same childlike sense of fear and disorientation. When the picture ended and Alfonso Cuarón finally allowed me to exhale, I took a moment on the pier outside Chicago’s IMAX theater and caught up on 100 or so minutes of furloughed coughs, my lungs going all Lithgow. I’d been nursing a cough that kept my wife sleeping in the guest room for nearly a week: Gravity was the only effective suppressant thus far. I don’t know if it was my heart or a piece of 3-D space junk lodged in my throat, but either way I was oddly grateful. With spirits raised, the news later that night that the government shutdown was official, including the lion’s share of NASA activity, was like screeching back down to Earth. In the real world, the space program may be on partial lockdown. But on movie screens, the possibilities are still breathtaking.

Correction, Oct. 7, 2013: This article originally misstated that the astronauts in the film 2010: The Year We Make Contact traveled from the Discovery II to the original Discovery. They floated from a Russian ship. (Return to the corrected sentence)