Jasmine (born Jeannette) French, the exquisitely dressed chasm of need at the center of Woody Allen’s misanthropic comedy Blue Jasmine, may be among the most unpleasant of all Allen protagonists (and if you have any memory of Kenneth Branagh as a scuzzy celebrity journalist in Celebrity, or Allen himself as a solipsistic author in Deconstructing Harry, you know she has some robust competition). As played by Cate Blanchett in a theatrical, screen-engulfing performance that leaves the audience feeling alternately dazzled and asphyxiated, Jasmine is the neurotic Woody Allen WASP diva to rule them all. Washing down her Xanaxes with a vodka martini (or in a pinch—and Jasmine gets into a lot of pinches—a straight shot of vodka) as she narrates her constant, anxious inner monologue to whoever will listen, Jasmine attains the paradoxical state of being fascinatingly tiresome.

The same pair of words might be used to describe Blue Jasmine, which, whether you like it or not, surely counts as one of Allen’s more unexpected films of the past decade. After a string of wistful ensemble comedies set in romantic European capitals (Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Midnight in Paris, To Rome with Love), he’s made an existentially bleak single-character study that bounces back and forth between a New York not usually inhabited by Allen characters—the posh Park Avenue/Hamptons circuit of the Wall Street superrich—and a curiously denatured San Francisco that doesn’t seem like a place ever inhabited by anyone.

As the film begins, Jasmine, whose husband Hal (Alec Baldwin) has been imprisoned for Madoff-style financial crookery, is flying across the country (first-class, despite her pleas of being dead broke) to stay with her sister Ginger (Sally Hawkins). Ginger, a divorced mother of two who works bagging groceries, lives in a different world from her sister’s and has barely seen Jasmine since she married into the high life. Ginger’s also nursing an old grudge; years before, she and her then-husband (a surprisingly touching Andrew Dice Clay) were among the patsies who lost their life savings by entrusting them to the conniving Hal.

Over the next few months, Jasmine settles into an uneasy existence at her sister’s place, eventually taking a job she had at first dismissed as insultingly remedial: working the front desk for a lecherous dentist (the great Michael Stuhlbarg, wasted in a flimsy part). Jasmine and Ginger fight a lot, often about Ginger’s boyfriend Chili (Bobby Cannavale), a working-class Stanley Kowalski type who (understandably) resents Jasmine’s condescension and snobbery. Convinced that her impeccable taste qualifies her for a career as an interior designer, Jasmine resolves to take a computer course that—from the bits of it we see—seems to be a simple here’s-how-to-get-online adult education class, yet which also somehow involves hours of furrowed-brow nightly study. No one in the movie appears to find this strange or offers to save Jasmine the trouble by tutoring her in basic browser usage. (This computer-class subplot is a small part of the film, but Allen’s tone-deafness as to the role of technology in modern life is worth noting—no wonder the version of 2013 San Francisco he shows us feels so fuzzily unspecific.)

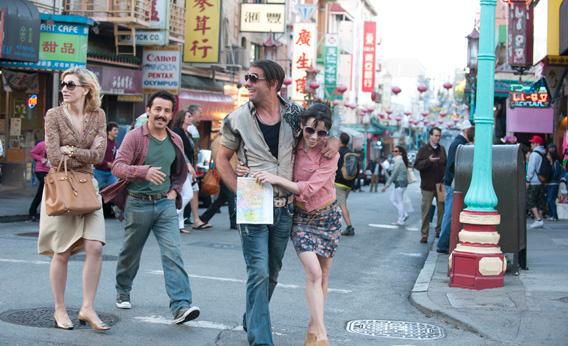

This mismatched pair of sisters—one short, brunette, earthy, and reasonably happy, the other tall, blond, ethereal, and miserable—soon find themselves in romantic hot water. Ginger pursues a flirtation with a gentle sound engineer (Louis C.K. in a tiny role), infuriating her hot-tempered boyfriend. And Jasmine, upon meeting a cultured, wealthy diplomat (Peter Sarsgaard), proceeds to invent a new past for herself out of whole cloth, one that doesn’t contain a crooked husband or a now-estranged stepson.

The choices Jasmine makes are so consistently reckless and self-sabotaging—and Blanchett’s performance so tremulously risky—that it’s impossible not to get a little caught up in the sickening momentum of her free-fall through the class system, as Allen cuts between her high-living past (charity fundraisers, polo ponies, cocktail-party debates about the value of owning a jet) and her modest living conditions in the present day. But Allen misses chance after chance to make this into something more than a vaguely topical reboot of A Streetcar Named Desire (to whose general storyline it hews fairly closely). The male characters in particular come off as too schematic: Almost without exception, they are either predatory rascals or clueless schlubs, mere foils for the squabbling, suffering sisters. As for Ginger and Jasmine, we spend an inordinate amount of screen time in their company without ever learning much about the complexities of either their past or present relationship. They were both adopted, we’re told at one point—but why does Ginger insist her sister was always their mother’s favorite? What was it about their upbringing that caused them to grow up into two such different people? (Judging from the unsympathetic portrait he draws of Ginger’s two hefty, obnoxious sons, Allen seems to hold childhood in about the same esteem as the sourly unmaternal Jasmine.)

Jasmine’s various pathological behavior patterns are on ample display—in scene after scene, we watch in squirming half-sympathy as she traps herself with self-aggrandizing lies. But though Blanchett excels at making us feel horrified pity for her character—especially in the last quarter of the film, as it becomes clear Jasmine’s spiritual redemption is probably not around the corner—her performance never sheds a certain stunt-like, calculated quality. Blanchett’s lavish, almost operatic turn as Jasmine sloshes against the sides of this insubstantial movie like liquid in a too-small container (maybe the room-temperature Stoli Jasmine is continually downing). There are many moments in which, as a viewer, you notice and admire Blanchett’s gestures and inflections, but very few in which you understand her deluded character’s motivations from the inside. She disintegrates beautifully before our eyes, not for any specific set of reasons the film maps, but because that’s what tragic heroines like Blanche DuBois (whom Blanchett played onstage in 2009, to general acclaim) are there to do.

As the movie’s last scene approaches—one of the darkest endings to a Woody Allen film I can remember, and one which gives the lie to this movie’s classification as a comedy—Jasmine has come unmoored from the relationships and belief systems that kept her tethered to reality: She’s become the kind of lady who walks around mumbling in a chic Chanel jacket, her mordant invective comprehensible only to herself. I doubt the director meant for Jasmine to be his stand-in at that moment, but I couldn’t help seeing the resemblance.