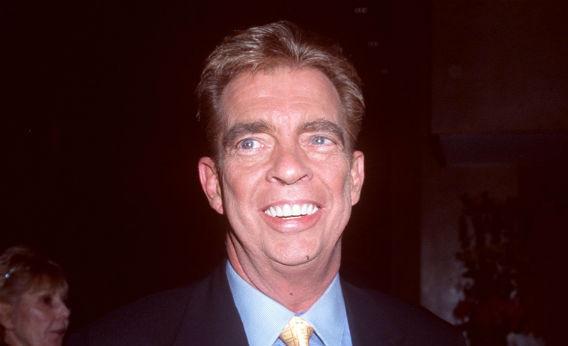

For a brief period in the late ’80s—long before the era of Fox News, Glenn Beck, and the 24-hour right-wing demagoguery cycle—there was The Morton Downey, Jr. Show, a Secaucus, N.J.-based talk show that was nationally syndicated after its host’s flamboyantly abrasive style proved to be a ratings magnet. Lit cigarette in hand, Downey would invade the personal space of his guests (among them Al Sharpton, Alan Dershowitz, Gloria Allred, Ron Paul, and assorted feminists, vegans, and other liberal punching bags), hurling insults at them with such force that he often appeared to be deliberately spitting at them. The show’s live studio audience—a moblike entity Downey referred to as “the beast”—ate it up, and for two years, Downey held the title of television’s rabble-rousing populist asshole-in-chief.

Then, as quickly as Downey’s star had risen, it began to fall—in part as a result of an embarrassing hoax in which he claimed to have been the victim of an assault by Nazi skinheads. (The circumstances of his downfall ironically recalled elements of the Tawana Brawley scandal, a racial tinderbox of a rape case in whose tabloid exploitation The Morton Downey, Jr. Show had played a very public and ugly role.) After only two years on the air, Downey’s program was canceled. He would die of lung cancer in 2001 after being a four-pack-a-day smoker for much of his life; his last few appearances on talk shows were as an anti-smoking activist.

The creators of the new documentary Evocateur, Seth Kramer, Daniel A. Miller and Jeremy Newberger, were working as partners at a film production company in 2008 when they discovered that, as teenagers, they had all shared a fascination with The Morton Downey, Jr. Show—two of them had even staged their own spoofs of the show in friends’ basements, a few moments of which we witness on home video. In some ways the tone of the documentary they’ve produced isn’t so far removed from the half-ironic tribute constituted by those old homemade clips. The filmmakers (and many of their interview subjects, who include the production team from Downey’s show, his lifelong best friend, and his daughter) never quite seem sure whether they’re there to celebrate Downey’s fearless showmanship or analyze his many personal pathologies, which included an inability to control his temper, a relentless hunger for notoriety, and a nasty misogynist streak. “Mort just understood performance,” marvels the former head of MTV, who was one of the first to spot Downey’s talent to provoke and entertain. “He knew how to manipulate,” recalls a friend and fellow radio host, adding, not without admiration, “He could have been a serial killer.”

The filmmakers also incorporate graphic-novel-style animation sequences, some of them mildly raunchy (and almost all of them annoyingly literal) to illustrate some of the speakers’ more colorful anecdotes. There are other tonally incongruous moments as well, including some unnecessarily sarcastic readings of Downey’s terrible self-published poetry by such marginally connected figures as former SNL regular Chris Elliott, who had an ongoing skit lampooning Downey’s show. I would have preferred to hear Elliott discuss Downey’s place in the media landscape of the time and what it was like to impersonate him as a young comic; Downey’s predictably execrable verse seems like fish too dull to bother shooting in a barrel.

But Downey’s life story is, in equal measure, fascinating and repulsive enough to make this documentary’s tonal tics worth overlooking. He grew up in show business, the son of Morton Downey Sr., a well-known pianist and radio crooner in the ’30s, and Barbara Bennett, a dancer who was the less successful sister of the movie stars Constance and Joan Bennett. After his parents separated in a public infidelity scandal, Downey’s father forbade his mother to have any contact with their children; she later drank herself to death, causing the young Mort to nurture a lifelong hatred for his father. An aide to the Kennedy family remembers the young Downey, whose father had a house near the Kennedy compound, as an idealist who wrote poetry inspired by the assassination of Robert Kennedy. (As she speaks, we see Downey appear, Zelig-like, in the background of photos from Ted Kennedy’s campaign headquarters). But as he moved into radio and later television, Downey came to understand the importance of finding an ideological niche and filling it.

Downey’s legacy, according to another friend, is that “passion plays on television, even if it’s an act.” The filmmakers push their thesis that Downey was the grandfather of modern-day trash-talk conservatism a little too hard—Rush Limbaugh’s ascent, for example, began at roughly the same time as Downey’s. And the firebrand rhetoric of Tea Party figures like Herman Cain and Michele Bachmann—both of whom are briefly and hectically interviewed at some sort of conservative conference—seems only tangentially related to Downey’s brand of tawdry buffoonery. (They have a special tawdry buffoonery all their own.)

Toward the end of its run, as reasonable guests (and major advertisers like Domino’s Pizza) became harder and harder to woo, The Morton Downey, Jr. Show became more and more of a Network-style sideshow, peopled by assorted crazies and attention-mongers: Nazi skinheads, strippers, conspiracy theorists. The speed of his downfall makes the last third of the documentary difficult to watch: We see an increasingly out-of-touch Downey berating and humiliating his guests and employees, then physically assaulting his wife before leaving her for a much younger woman, whom he proceeds to nearly bankrupt himself spending his money on. (They would remain together until his death.) He’s an unredeemable bastard, but in his pettiness and desperate need for recognition, there’s something moving too. The man whose logo was a cartoon of a wide-open, yammering mouth would probably not have objected to this mostly unflattering but ultimately respectful portrait. It’s crude, funny, hard to look away from, and mercifully short—just like Morton Downey Jr.’s moment in the sun.