A few years ago, writing about Oren Peli’s Paranormal Activity franchise, Ti West’s House of the Devil, and other experiments in craft-conscious, low-budget horror, I gave a name to the loosely defined style I saw these movies as sharing: “artisanal horror.” The term caught on only in my own brain, where it’s become a handy taxonomic classification for a subgenre that seems here to stay, even in the age of the big-budget, special-effects-laden franchise. The horror genre has always welcomed tinkerers—inventive filmmakers who are interested in taking genre’s conventions apart and fitting them back together in novel ways. If the desired effect of maximum audience creep-out has to be achieved on a minimal budget, so much the better. Artisanal horror directors place a high value on cheapskate ingenuity, the trick of scaring the audience pantsless with the simplest possible effect: an unexpected camera movement, a barely glimpsed shadow, a hand reaching for a doorknob. And they tend to pay some sort of tribute to the genre’s roots in low-budget exploitation, sometimes by citing their B-movie forebears outright (as did Joss Whedon’s Cabin in the Woods, which was artisanal in spirit if not in budget), sometimes just by letting the seams in the monster costumes show.

Two new movies—very different, but both very good— showcase the expressive range of the artisanal-horror style. One, Don Coscarelli’s John Dies at the End, is a gleefully crummy buddy comedy that uses horror-movie conventions as catapults to hurl the audience down one “whoa, dude!” narrative wormhole after another. The other, Andy Muschietti’s Mama, is a somber, elegant variation on a classic fairytale that takes us almost nowhere unexpected but still makes the trip scary as hell.

Since Don Coscarelli’s breakthrough at the age of 23 with Phantasm (1979)—a bracingly original screamer that quickly became a cult classic and whose airborne metallic sphere of death will forever haunt my dreams—his movies have been few and far between but dependably bizarre. Bubba Ho-Tep (2002) told the story of a geriatric Elvis Presley (Bruce Campbell) who joins forces with a black man claiming to be John F. Kennedy (Ossie Davis) to fight a reanimated Egyptian mummy that’s sucking up the souls of their fellow nursing-home inmates—a thumbnail description that does significant injustice to the coiling ingenuity of that movie’s plot.

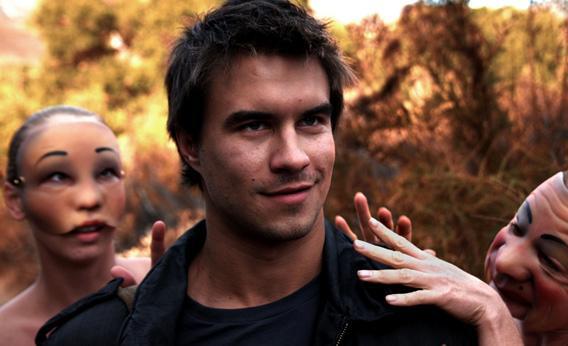

John Dies at the End, based on a comic horror novel of the same (excellent) title by David Wong, has a story that’s similarly irreducible to summation: A pair of smartass twentysomething friends, Dave (Chase Williamson) and John (Rob Mayes), come into possession of a dangerous drug called Soy Sauce, which gives its users seemingly limitless powers of awareness and prescience. As a skeptical journalist (Paul Giamatti) listens to Dave’s story in the booth of a Chinese restaurant, alternate realities and interpretations thereof succeed one another like Kleenex from a box: Are Dave and John mixed up in a string of brutal murders that happened the night they first took the drug? Or are they the murderer’s next victims? Is it possible that John is already dead but continuing to transmit crime-solving tips from beyond the grave on a psychic phone made of bratwurst? And not to sound paranoid, but what if space aliens are behind this whole thing?

John Dies at the End is joyously heterodox in its method, an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink mélange of sci-fi, black comedy, and action, with disquieting body-horror sight gags that at times recall David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch. (A doorknob suddenly transforms into a dangling penis; a mustache rips itself off a man’s face and flies around the room like a bat.) The story’s rabbit holes got so deep that I can’t actually tell you whether the movie’s title is a spoiler or not, but I loved John Dies at the End for so confidently whisking the viewer to a place where the question “Well, did he die or didn’t he?” seems hopelessly un-nuanced and square.

Courtesy Universal Pictures.

If John Dies at the End represents the wild side of artisanal horror, Mama resides somewhere closer to the classical end of the spectrum: It’s a minimalist riff on an age-old ghost story. Jessica Chastain (looking uncharacteristically Goth but gorgeous in raccoon-eye makeup and a brunette shag) plays Annabel, a less-than-maternal aspiring rock bassist who finds herself in sole charge of two disturbed young girls after they’re discovered living an animal-like existence on their own in a remote forest cabin. (A grim precredit sequence explains how they got there.) Her boyfriend (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau), the girls’ uncle, insists on adopting the children before falling into a narratively convenient coma, the better to strand Annabel in a house with two increasingly freaked-out and freaky little girls.

It’s not hard to forgive Mama this introductory plot contrivance, because the story at the movie’s heart is so simple and powerful we can’t wait to get to the good stuff either. As Annabel struggles to build some kind of relationship with the children, resilient Victoria (Megan Charpentier) and her more damaged younger sister Lilly (Isabelle Nélisse), she becomes aware of a fourth presence in the house—a malevolent, wispy something that for most of the movie we, like Annabel, witness only out of the corner of our eye but that seems to hold the girls transfixed. According to the child psychiatrist who’s treating Victoria (Daniel Kash), the children invented an imaginary mother during their years of parentless existence in the cabin. Is it possible their shared hallucination has Annabel seeing things as well? Or is “Mama,” the maternal wraith the girls insist lives in their closet, all too real and none too happy about sharing her charges with a flesh-and-blood woman?

Like most haunted-house stories, Mama gets steadily less scary as its (for the most part, fairly predictable) secrets unfold. But even if the beats are familiar, Muschietti sustains a remarkable mood throughout: wintry, elemental and stark, like a late Sylvia Plath poem. This relentlessly spooky but almost gore-free movie ends with a woman-on-ghost confrontation at the precipice of a steep cliff that’s as stark an allegory for the power of maternal love as Sigourney Weaver’s climactic battle with the mother-monster in Aliens. (“Get away from her, you bitch!”) You’d have to be a monster yourself not to be moved by this final showdown, in which Chastain’s previously diffident character suddenly grasps how unbearable it would be to lose either of these children and understands in that same moment that they are truly hers.